The Role of Public Policy

@ 1995 The Intentional Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK

All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First printing July 1995

The Development in Practice series publishes reviews of the World Bank's activities in different regions and sectors. It lays particular emphasis on the progress that is being made and on the policies and practices that hold the most promise of success in the effort to reduce poverty in the developing world.

This book is a product of the staff of the World Bank. and the judgments made herein, do not necessarily reflect the views of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent.

Photo credits: Maurice Asseo

Library of Congers Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Toward gender equality: the role of public policy. p. cm-(Development in practice)

Includes bibliographer references (p. 70)

ISBN 0-8213-3337-2

1. Women-Government policy.

2. Women's rights.

3. Sex discrimination against women.

4. Economic development.

1. Series:

Development in practice (Washington. D.C.)

HQ 1 236.T68; 1995

305.4-dc20 95-631

CIP

TWENTY years ago in Mexico the First World Conference on Women inspired a movement that has helped to reduce gender inequality worldwide. Illiteracy among women is declining, maternal mortality and total fertility rates are beginning to fall. and more women are participating in the labor force than ever before. However. much remains to be done.

In low-income countries women are often denied health care and basic education. Worldwide. women face limited access to financial services, technology. and infrastructure. They are locked into relatively low-productivity work. In addition to performing household tasks and child-rearing duties, women work longer hours for lower pay than most men. And. most discouraging of all. hundreds of thousands of women each year are subject to gender-related violence.

Persistent inequality between women and men constrains a society's productivity and, ultimately slows its rate of economic growth. Although this problem has been generally recognized evidence on the need for corrective action is more controlling today than ever.

This report written for the Fourth World Conference on Women is intended as a reference to strategies for promoting gender equality and. consequently enhancing economic efficiency. It pulls together evidence, including case studies, that demonstrates the need for governor action to improve the economic status of women. It points out how public policy can and should support services and infrastructure that provide the highest social returns and that are most heavily used by women. The report also aims to stimulate creative solutions to the problem of gender inequality by high lilting innovative and sometimes not obvious strategies that have proved successful. A study in Morocco, for instance, shows that paving public roads to schools increases by 40 percent the probability that local girls will attend classes.

Policy reform that provides an enabling environment for economic growth goes hand in hand with investing in people. The success of one strategy draws on the success of the other. No efforts at gender equality. however, can be successful without the participation of women themselves.

As the international community gathers in Beijing for the Fourth World Conference on Women, the World Bank stands ready to assist client governments in response to the challenges ahead. The Bank believes that by advancing gender equality, governments can greatly enhance the future well-being and prosperity of their people.

Armeane M. Choksi Vice President Human Capital Development and Operations Policy The World Bank

THIS REPORT was prepared by a team led by Kei Kawabata and comprising Alison Evans, Zafiris Tzannatos. Tara Vishwanath, and Rekha Menon. The work was carried out under the direction of Minh Chau Nguyen and the overall guidance of K. Y. Amoako. Valuable contributions were made by Joyce Cacho, Lionel Demery, Shahid Khandker, and Kalanidhi Subbarao.

Background papers for the report were prepared by team members and by Anjana Bhushan; Lynn Brown and Lawrence Haddad; Florencia Castro-Leal, with Ignacio Tavares and Ramon Lopez; Roberta Cohen; Monica Fong: Roger Key, with Beverly Mullings; Andrew Mason; and Veena Siddharth.

An external review group and a Bankwide advisory committee provided valuable guidance at all stages of the report's preparation. Kalpana Bardhan. Pranab Bardhan, Nancy Folbre. and T. Paul Schultz were the external reviewers. Harold Aldennan, Jean-Jacques Dethier, Louise Fox, Sunita Gandhi, Chris Grootaert, Jeffrey Hammer, Tariq Husahl, Elizabeth King, Augusta Molnar, Helena Ribe, and Paula Valad made up the advisory committee. The report was edited by Jo Bischoff, Richard M. Crum, and Fiona Mackintosh; Benjamin Crow provided word-processing and graphics support.

The report also reflects the contributions of the participants in consultations held with nongovenamental organizations on March 1S, 1995, in New York. Data supplied by the United Nations and its agencies. particularly the International Labour Organization, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the United Nations Statistical Office, and the World Health Organization, were invaluable for the preparation of the report.

The production of the report was made possible by the assistance of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which has given unwavering support to the protnotion of gender equality.

Expected number of years of formal schooling The total number of years of schooling that a child of a certain age can expect to receive if current enrollment patterns remain unchanged.

Literacy rate. The proportion of the adult population that can read or write. This indicator is not always accurate because it is self-reported and represents past investments in schooling. It is often defined only with respect to selected languages and may not take into account the progress being made in many countries through literacy campaigns.

Life expectancy AT BIRTH The number of years a newborn infant would live if prevailing patterns of mortality at the time of birth were to remain unchanged throughout the child's life.

Maternal mortality ratio. The number of women who die in pregnancy and childbirth per 100,000 live births: A measure of the risk that women face of dying from pregnancy-related causes.

Unless otherwise specified, dollar amounts are current U.S. dollars. A billion is a thousand million.

The data used in this report cover a range of time periods and are from more than 100 countries (both developing and industrial).

Unless otherwise specified, geographic regions are those used by the World Bank in its analytical and operational work and are defined as follows:

sub-Saharan Africa countries south of the Sahara except Africa.

East Asia and the Pacific: low- and middle-income economies of East and Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

Europe and Central Asia. middle-income European countries and the countries that formed the former Soviet Union.

Latin America anti the Caribbean all American and Caribbean economies south of the United States.

Middle East and North Africa all the economies of North Africa and the Middle East.

South Asia: Bangladesh, Bhutan, India. Myantnar, Nepal, Pakistan. and Sri Lanka.

THREE messages echo throughout this document:

The causes of gender inequality are complex, linked as they are to the intrahousehold decisionmaking process. However the decisions are made. the intrahousehold allocation of resources is influenced by market signals and institutional norms that do not capture the full benefits to society of investing in women. Low levels of education and training. poor health and nutritional status, and limited access to resources depress women's quality of life and hinder economic efficiency and growth.

It is therefore essential that public policies work to compensate for market failures in the area of gender equality. These policies should equalize opportunities between women and men and redirect resources to those investments with the highest social returns. Of these investments. female education, particularly at the primary and lower-secondary level, is the most important, as it is the catalyst that increases the impact of other investments in health, nutrition, family planning, agriculture, industry, and infrastructure.

Women themselves are agents for change because they play a key role in shaping the welfare of future generations. Public policies cannot be effective without the participation of the target group-in this case. women, who make up more than half the world's people. Their views need to be incorporated into policy formulation.

Over the past two decades considerable progress has been made in reducing the gender gap world wide.

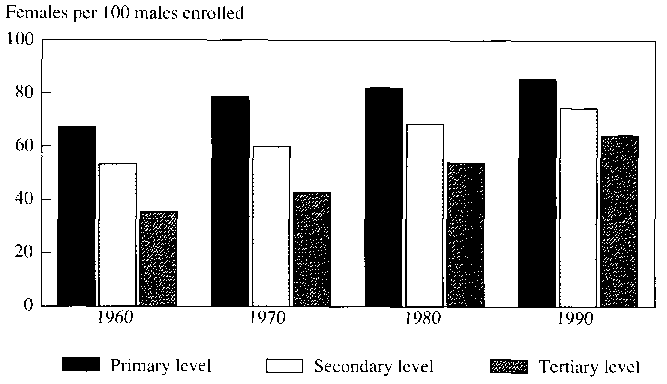

In 1960. for every 100 boys enrolled in primary school. there were 65 girls. In 1990 the ratio had risen to 85.

In 1980 an average six-year-old girl in a developing country could expect to attend school for 7.3 years. By 1990 this figure had Increased to 8.4 years.

Since the 1950s the female labor force has grown twice as last as the male labor force. Worldwide, more than 40 percent of women over 15 years of age are now in the labor force; in developing countries women account for 30 percent of the labor force (These figures. it should be noted, do not fully reflect women's participation in the informal sector as unpaid family members in agriculture.)

Nevertheless. inequalities between men and women persist in many important areas.

Despite women s biological advantage, their mortality and morbidity rates frequently exceed those of men, particularly during childhood and the reproductive years.

Traditionally women are employed in lower-pay jobs and in a narrower range of occupations than are men. Women's wages are typically only 60-70 percent of wages earned by men.

Whether in private sector employment or public sector decisionmaking, women are less likely to be in positions of responsibility than are men.

The causes of the persistent inequality between men and women are only partially understood. In recent years attention has focused on inequalities in the allocation of resources at the household level. as seen in the higher share of education, health. and food expenditures boys receive in comparison with girls. The decisionmaking process within households is complex and is influenced by social and cultural norms market opportunities, and institutional factors. There is considerable proof that the intrahousehold allocation of resources is a key factor in determining the levels of schooling. health. and nutrition accorded household members.

Inequalities in the allocation of household resources matter because education, health. and nutrition are strongly [hiked to well-being, economic efficiency. and growth. Low levels of educational attainment and poor health and nutrition aggravate poor living conditions and reduce an individual's capacity to work productively. Such economic inefficiency represents a significant loss to society and hampers future economic growth.

Social returns to investments in women's education and health a? e significantly greater than for similar investment in men.

The social and economic losses are greatest when women are denied access to basic education and health care. Data from around the world show that private returns to investments in education are the same for women as for men and may even be marginally higher (Psacharopoulos 1994). More importantly. social returns (that is, total benefits to society) to investment in women's education and health are significantly greater than for similar investments in men, largely because of the strong correlation between women's education, health, nutritional status. and fertility levels and the education. health, and productivity of future generations. These correlation are even stronger when women have control over the way resources are allocated within the household.

Wage differentials between women and men in the market are closely linked to educational levels and work experience. since on average. women earn 30-40 percent less than teen' it is not surprising that fewer women than men participate in the labor force. This wage disparity, reinforced by discriminality institutional norms, in turn influences the intrahousehold division of resources. A vicious circle ensues as households invest less in daughters than in sons in the belief that investment in girls yields fewer benefits. As a result. many women are unable to work outside the household because they lack the education or experience that men have.

The decision not to participate in the labor force does not necessarily reflect a woman's own choice, no' does it always correspond to the optimum use of household resources. Furthermore. the market wage does not take into account the social benefits of educating and hiring women. Discrimination in households and in the market carries not only private costs for individuals and households but social costs for society as well.

Public policies for reducing gender inequalities are therefore essential for counteracting market failure and improving the well-being of all members of society. Investing in women's education and health expands their choices in labor markets and other income-generating activities and increases the rate of return on a household's most valuable asset-its labor.

The decision to allocate women's time to the type of non wage work women typically carry out within the household. such as child care. food preparation, and, in low-income countries especially, subsistence farming and the collection of fuel wood and water, has less to do with economics than with social conventions and norms. These nones can have a strong influence on the household division of labor, even in industrial economies, where women's levels of human capital are equal to-and some times higher than those of most men

The economy pays to this inequality in reduced labour productivity today and diminished national output tomorrow

Whether this division of labor is appropriate is, essentially, for society to decide. However. there is no doubt that women's entry into the labor market and other spheres of the economy is directly affected by the extensive amounts of time they traditionally devote to household maintenance and family care. Most men do not make similar allocations of time in the home. Such inequality constrains women's employment choices and can limit girls' enrollment in schools. The economy pays for this inequality in reduced labor productivity today and diminished national output tomorrow. Public policy can address inequalities in the household division of labor by supporting initiatives that reduce the amount of time women spend doing unpaid work. Examples of such interventions include improved water and sanitation services, rural electrification, and batter transport infrastructure.

Constraints on female employment opportunities arising from the household division of labor are compounded by institutional norms operating within the labor market. Although overt wage discrimination is illegal in many countries, employers frequently segregate jobs or offer less training to women workers. Employers often perceive the returns to investing in women workers as lower than those for men mainly because of women's primary role in childbearing.

Lack of access to financial services, to land, and to intonation and technology compounds the unequal treatment of women. Requirements for collateral, high transaction costs, and limited mobility and education contribute to women s inability to obtain credit. When women do have access to credit, the effect on household and individual well-being is striking. Bon-owing by women is linked to increased holdings of non-land assets, to improve in the health status of female children, and to an increased probability that girls will enroll in school. Independent access to land is associated with higher productivity and. in some cases, with greater investments by women in land conservation.

If the benefits from investing in girls and women are so great and can be quantified. why do households and employers underinvest in women? The main reason is that. as discussed above. markets fail to capture the full benefit to society of' investing in women and girls. Where the market fails or is absent. government must take the lead Public policy can contribute directly and indirectly. to reducing gender inequalities by, for example:

Modifying the legal and regulatory framework to ensure a opportunities

Ensuring macroeconomic stability and improving, microeconomic incentives

Redirecting public policies and public expenditures to those investments with the highest social returns

Adopting targeted interventions that correct for gender inequalities at the micro-level.

Modifying the law to eliminate gender discrimination and equalize opportunities for women and men is an important first step. However. legal reform by itself does not ensure equal treatment. Further public action is required to make sure that gender-neutral laws are enforced at the national and local levels.

Sound economic policies and well-functioning markets are essential for growth, employment generation, and the creation of an environment in which the returns to divesting in women and owls can he fully realized. Economic instability and price distortions can hinder the process. Consequently. sound macroeconomic management is critical. In general. two sets of policies are necessary: one emphasizing macroeconomic stability and the elimination of price distortions. the other focusing on labor-demanding growth and a reorientation in public spending toward basic services with high social returns- such as education. health care and water supply.

Gender inequalities in the distribution of the benefits of public spending frequently arise because of a bias within households that limits women's access to publicly provided services. In addition, the services provided by public spending often are of less benefit to women than to men. Public policy can help remedy this problem by rearranging expenditure priorities among sectors and within the social sectors. It can ensure support for those services and types of infrastructure that offer the highest social returns to public spending and that are most heavily used by women and children. such as water supply anti sanitation services and rural electrification.

Finally general policy interventions may not be enough. and programs that specifically target women and girls may be required. Targeting is justified. Governments can no longer afford not to invest in women gable on two grounds. First. because women are disproportionately represented among the poor. targeting women can be an effective strategy for reducing poverty (broadly defined to include limited access to services. re sources, and other capability-enhancing factors). Second. where gender differences are wide, targeting-for example. the provision of stipends so that girls can attend school-they be needed to capture social gains and increase internal efficiency

Governments can no longer afford not to invest in women. The evidence on the high private and social returns to investments in women and girls cannot be ignored. By directing public resources toward policies and projects that reduce gender inequality. policymakers not only promote equality but also lay the groundwork for slower population growth, greater labor productivity, a higher rate of human capital formation, and stronger economic growth However, none of these developments can be sustained without the participial of women themselves. Governments and collaborating institutions must listen more carefully to the voices of individual women. including policymakers. and to women's groups. By working with others to identity and implement policies that promote gender equality, governments can make a real difference to the future well-being and prosperity of their people.

ALTHOUGH the gap between opportunities for men and women is narrowing. inequalities persist, especially in certain regions. This report examines four major development indicators: educational attainment, maternal mortality. life expectancy. and economic participation outside the household. All four are closely related to each other and in turn are closely correlated with individual well-being. These indicators provide a broad picture of trends in gender inequality and their impact on the relative well-being of women and of men.

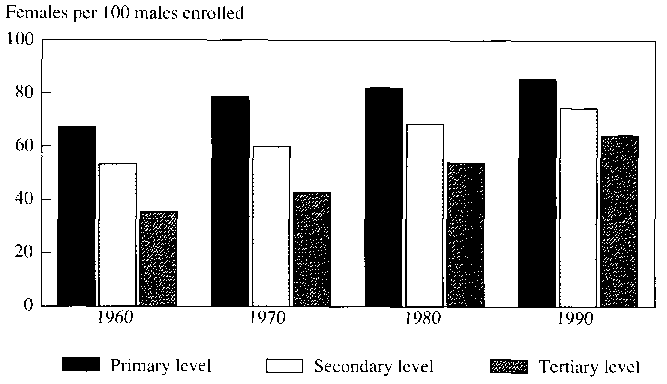

Despite the progress in raising educational enrollment rates for both males and females across all regions in the past three decades, growth in educational opportunities at all levels for females lags behind that for males (figure 1.1). In 1990 an average six-year-old girl in a developing country could expect to attend school for 8.4 years. The figure had increased from 7.3 years in 1980-but an average boy of the same age in a developing country could expect to attend school for 9.7 years The gender gap in expected years of schooling is widest in some countries in South Asia, the Middle East, and Sub-Saharan Africa (see figure 1.2). Gender differences in access to education are usually worse in minority populations such as refugees and internally displaced persons. of which only a few children go to school.

The latest available figures show that 77 million girls of primary school age (6-11 years) are not in school, compared with 52 million boys (figure 1.3). Moreover, even these gross enrollment rates often mask high absenteeism and high dropout rates. Dropout rates are notably high in low-income countries but vary by gender worldwide and within regions. The rates for girls tend to be linked to age, peaking at about grade 5 and remaining high at the secondary level (Herz and others 1991) Cultural factors, early marriage, pregnancy, and household responsibilities affect the likelihood that girls will remain in school.

Although the gross enrollment rate is an acceptable indicator of progress in education, most studies use literacy rates as an indicator of well-being. Overall illiteracy rates have decreased among adults in low- and middle-income countries, but the percentage of illiterate women in the world is still higher than the percentage of illiterate men. Older women constitute the largest share of the illiterates in the world today, a consequence of past inequalities in access to education. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia more than 70 percent of women age 25 and older are illiterate (United Nations 1991).

At post-secondary levels. where the gap in enrollment between women and men is wider, there is implicit "gender streaming," or sex segregation, by field of study, even in areas with snore female than male enrollees. Gender streaming. which is widespread in both developing and industrial countries, prevents women from acquiring training in agriculture, forestry, fishing, "hard" sciences, and engineering (figure 1.4).

Over the past two decades life expectancy at birth has increased for both men and women in all regions of the world. In industrial countries women tend to outlive men by six to eight years on average: in low-income countries gender differences are much narrower (two to three years). Despite women's biological advantage, female mortality and morbidity rates frequently exceed those of men, particularly during early childhood and the reproductive years.

During the reproductive period the most Important causes of morbidity and mortality among women are high fertility and abortion rates, vulnerability to sexually transmitted diseases (STDS), genital mutilation. and gender violence. Each year, about 500,000 women worldwide die from the complications of pregnancy and childbirth. Maternal mortality ratios for developing and industrial countries vary greatly: the rates in parts of South Asia are among the world's highest, in some cases exceeding 1,500 per 100.000 live births. In Sub-Saharan Africa where the ratio is 700 maternal deaths per 100.000 live births, a woman runs a 1 in 22 lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy-related causes, but in northern Europe the risk falls to 10 in 100,000 (United Nations 1993). In the transition economies of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, the rates are around 40 to 50 per 100,000 live births

A major cause of maternal deaths is complications from unsafe abortions. Abortion-related deaths are highest in South and Southeast Asia. followed by Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean. Lack of access to contraceptives can mean that abortion, is used as a form of birth control. For example, in parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia abortions are more numerous than live births (World Bank 1994b), and abortion rates were as high as 1.76 per live birth in Russia prior to the transition.

As increasing numbers of women become aware of and learn to use contraceptives, total fertility rates are falling worldwide. The exception is Sub-Saharan Africa where the total fertility rate averaged 6.4 between 1985 have been infected by HIV. The World Health organization (WHO 1994) estimates that more than 13 million women will have been infected by HIV by 2000 and that about 4 million of that number will have died (figure 1.5 In Atrica, where 10 million adults are infected with the virus, ode-half of all newly infected adults are women, and more than 5 million are women of childbearing age. In Asia almost half of all adults newly infected with the virus are women, compared with less than 25 percent just six years ago.

The mortality risk for females is high during the reproductive years. but it is even higher during infancy and early childhood. Between 1962 and 1992 INFANT mortality in the developing world decreased by 50 percent (UNICEF 1993 However, in seventeen of the twenty-nine developing countries for which recent survey data are available, female children age 1-4 were found to have higher mortality rates than male children. despite girls? biological advantage (World Bank 1994b). In many of these countries the underlying cause of high mortality among girls is the parents' bias toward boys, who receive the best food and medical care.

Genital mutilation, prevalent in twenty-eight countries, is performed on 2 million young girls yearly. The practice leads to long-term morbidity, complications during childbirth, mental trauma, and even death. Table 1.1 summarizes the best available statistics on this practice for selected countries.

The time women spend on paid and unpaid work is typically greater than the time men spend in the labor market (see table 1.2 for an example). Unpaid family work is rarely recorded in official statistics. It manifests itself only indirectly in the labor market in the form of gender differences in labor force participation rates. sector of employment, hours of work, and wage level.

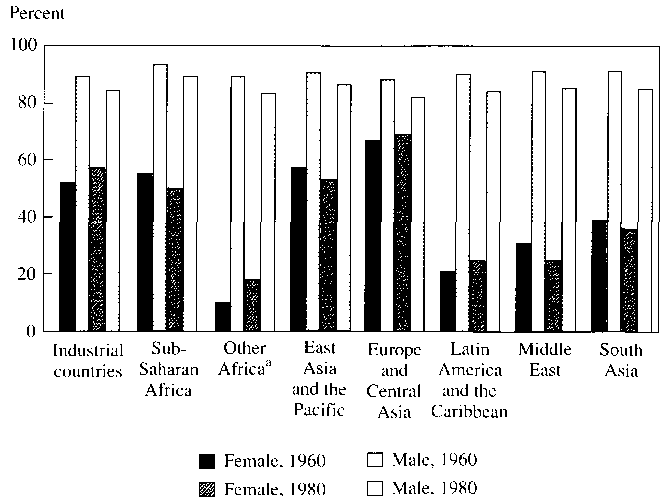

On the whole. labor force participation rates for women are lower than those for men (figure 1.6). However. these differences are often exaggerated because the definition of the participation rate fails to capture many aspects of women's work, particularly time spent on childbearing, childbearing. and other household tasks. Men are usually in the labor force throughout the prime working years (age 20-60), and their participation rates are typically more than 90 percent in virtually every country. Female participation rates vary widely across countries. In 1990, for every ten men in the labor force there were two women in the Middle East and North Africa, three in South Asia. six in Sub-Saharan Africa, and seven in Southeast Asia (United Nations 1991). Worldwide, 41 percent of women age 15 years or over are in the labor force, but in developing countries the corresponding figure is 31 percent.

These numbers are deceptive, however, because they do not take into account the agricultural work for which women in developing countries are responsible within the family For example, the Dominican census of 1981 reported that only 21 percent of rural women participated in the labor force, but just three years later a special study suggested a figure of 81 percent. The census had omitted such activities as cultivating gardens and caring for domestic animals In India different definitions of what constitutes "work" have resulted in estimated participation rates as low as 13 percent and as high as 88 percent (Beneria 1992).

Tens of Millions of Women Suffer Female Genital Mutilation.

Table 1.1 female genital mutilation

|

Country |

Estimated prevalence (percent) |

Estimated number of women affected (millions) |

|

Djibouti |

98 |

0.2 |

|

Egypt |

50 |

13.5 |

|

Eritrea |

90 |

1.5 |

|

Ethiopia |

90 |

22.5 |

|

Kenya |

50 |

6.3 |

|

Nigeria |

50 |

29.2 |

|

Sierra Leone |

90 |

2.0 |

|

Sudan |

89 |

118 |

In Sri Lanka's Dry Zone, Women Work Longer Hours than Men.

Table 1.2 distribution of monthly work hours per month)

|

Peal. Season |

Slack season |

|||

|

Activity |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

Agricultural production |

298 |

299 |

245 |

235 |

|

Household tasks |

90 |

199 |

60 |

220 |

|

Fetching water and firewood |

30 |

50 |

:30 |

60 |

|

Social and religious duties |

8 |

12 |

15 |

15 |

|

Total work hours |

426 |

560 |

350 |

530 |

|

Leisure and sleep |

294 |

160 |

370 |

190 |

Women are usually employed in different sectors than men. Most of women's nonagricultural employment is in the service sector. but in developing countries female employment in manufacturing has been increasing and is catching up with female employment in services (ILO/ INSTRAW 1985). Women in manufacturing tend to be concentrated in only a few sub sectors: more than two-thirds of the global labor force in garment production is female. and this subsector absorbs almost one-fifth of the female labor force in manufacturing (UNIDO 1993). Men's employment is more evenly distributed across other sectors such as mining manufacturing, construction, utilities, and transport.

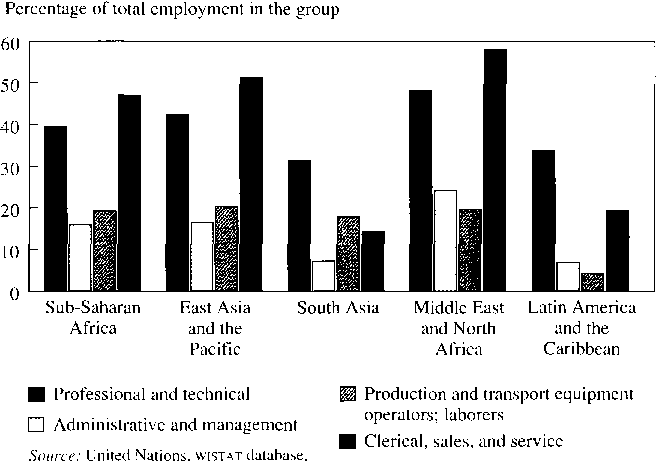

Over their lifetime, women change their employment status more often than do men. They are also more likely to be self-employed or employed in occupations with flexible house such as subcontracted home work. Regardless of the sector in which they are employed, women tend to work in a narrow range of occupations. Only a few women are in high-paying jobs or in positions with significant responsibility. Nearly two-thirds of the women in manufacturing ate laborers, machine operators. and production workers; only 5 percent ate professional and technical workers and only 2 percent are administrators and managers (UNIDO 1993). However. there are regional differences: women occupy nearly 60 percent of clerical, sales. and service jobs in Latin America and the Caribbean but fewer than 20 percent of similar positions in South Asia North Africa. and the Middle East (figure 1.7).

Wages paid to women are typically about 60-70 percent of those paid to men. About one-quarter of the gender wage gap is explained by differences in educational levels, labor market experience, and other human capital'' characteristics (Psacharopoulos and Tzannatos 1992 Horton 1994). The gender wage gap can also be explained in part by women's lower participation in the labor market-a consequence of domestic and other demands on their time and, possibly, of discriminatory employment practices.

Significant changes in the global economy have affected patterns of employment and working conditions for men and women worldwide. "Globalization" is associated with the deregulation of product and labor markets, with regionalization. and with the liberalization of international trade. In turn. these processes at-e associated with increased female participation in the labor force and with the at-owing "casualization'' of employment, as seen in the growth of part-time work in industrial economies. However, the net effect of globalization on women workers is not yet clear. Growth in the international traded service sector (for example, banking and telecommunications) seems to have offered women in developing countries greater employment opportunities. In addition, the participation rate of women in manufacturing jobs has increased faster than that of men. Women's average participation in the manufacturing labor force is now around 30 percent for both developing and industrial countries.

Worldwide, the number of women employed in export manufacturing has been increasing rapidly, even though this sector employs only a small fraction of all women workers. In Mexico, for example, the number of women employed in export manufacturing rose by nearly 15 percent a year in the 1980s (Jurisman and Moreno 1990). However, employment in this sector has been increasing more rapidly for men than for women, partly because of

technological upgrading over time and partly; because women are less educated and tend to remain in low-skill occupations (Baden 1992).

Women now account for a growing share ret wage employment they tend to stay longer in the labor force than ever before

Despite persistent gender inequalities in the labor market. some recent trends are encouraging. Increasing educational opportunities and decreasing fertility rates have fed to an increase in the number of women entering the labor market. since the 1950s the female labor force has expanded twice as fast as the male labor force. Women now account for a growing share of wage employment. and they tend to stay longer in the labor force than ever before The narrowing of the gender gap in labor force participation is enabling women to accumulate the work experience necessary tot- improving their job opportunities and increasing their amines. In the formal sector more and more women are working in occupations and sectors once dominated by men. and in many countries women s wages relative to men s have increased over time

The data in this chapter illustrate some aggregate trends but they cannot tell US anything about the processes behind the persistence of gender inequality. For a more detailed look at these processes. We turn in the next chapter to a growing body of empirical evidence generated at the household and enterprise level. These studies provide a telling insight into the way in which gender inequalities are being challenged particularly by women At the same time these inequalities are reinforced by economic, legal. and cultural incentive systems that discriminate against women Discrimination continues despite compelling evidence showing that less inequality especially within the household. is associated with heftier welfare outcomes for children and better economic outcomes for the household as a v hole.

Inequality women and men limits productivity ultimately slows economic growth. early empirical studies (for example, Kuznets 1955) suggested that income inequality would increase with economic growth during the initial phases of development. This chapter, however. starts with the hypothesis that there is not necessarily a tradeoff between inequality and growth and. indeed that high inequality especially as it affects human capital. hampers growth (Fields 1992: Birdsall and Sabot 1994).

Both theory and empirical evidence point to the importance of human capital in creating the necessary conditions for productivity growth and in reducing aggregate inequality in the future. In addition. women s human capital generates benefits for society in the form of lower child mortality. higher educational attainment improved nutrition. and reduced population growth. Inequalities in the accumulation and use of human capital at-e related to lower economic and social well-being for all.

In recent years, attempts to explain persistent gender inequalities in the accumulation and use of human capital have focused on the key role of household decisionmaking and tile process of resource allocation within household Households do not make decisions in isolation. however: their decision are linked to market prices and incentives and are influenced by cultural legal and state institutions. These institutions indirectly affect not only the returns on household investment but also access to productive resources and employment outside the house hold.

Household decisions about the allocation of resources have a profound effect on the schooling, health care, and nutrition children receive. The mechanisms used to make these decisions and the effect of the decisions on the well-being of individual household members are not fully understood. Two frameworks for thinking about household decisions are the unitary household model and the collective household model (see box 3.1)

|

BOX 2.1 Two models of household members having their own prefer decisionmaking encase. Decisions on allocating resources reflect market rates of return. The unitary household model assumes but they also mirror the relative bar that household members pool regaining power of household members sources and allocate them according within the collective (Manser and to a common set of objectives and Brown 1980: McElroy and Homey goals. Households maximize the joint 1981). Bargaining power is a function welfare of their members by allocating of social and cultural norms. as well income and other resources to the in as of such external factors as opposed individuals and enterprises that promise "unities for paid work, laws governing the highest rate of return as reflected inheritance, and control over producing prices and wages. An increase initiative assets and property rights. These household income increases the well factors influence the terms governing being of all household members. |

Policy interventions based on the sources and decisions about how unitary household model aim to in those resources are used within the crease household welfare, but they household. Thus, an increase in do not necessarily affect all household income may benefit some hold members in the same way. Some household members but leave others household members may be worse unaffected or worse off. The outcome off, for example, if they lose control depends on a member's ability to exover certain resources; others may excise control over resources both in be better off. in which case house-side and outside the household, and it hold welfare is not maximized. cannot be assumed that individual well

Under the collective household being increases as household income model. the welfare of individual house-rises. (Collective household models do hold members is not synonymous with not exclude the possibility that the universal household welfare. Resources unitary model may be the best approximate not necessarily pooled, and the motion of household decisionmaking household acts as a collective, with in some contexts.)

The collective household model helps explain why gender inequalities persist even though household becomes increase over time The next sections adopt a collective household framework to explain how these inequalities exact costs in forgone productivity, seduced welfare for individuals and households, encl. ultimately. slower economic growth.(fender Inequalities in Human Capital )

There are strong complementaires between education. health. and nutrition on the one hand, and increased well-being, labor productivity, and growth. On the other. Inequalities in resource allocation that limit household members' educational opportunities. access to health care, or nutrition are costly to individuals, households, and the economy as a whole.

At the household level. gender differences in access to education are closely related to inequalities in the shares of household education expenditures allocated to boys and to girls This finding stands even though private returns to girls' schooling are similar to or marginally higher than. those to boys' schooling (figure 2.1; see also Schultz 1988: Mwabu 1994). In this case. parental choice reflects the relatively greater restrictions on educational opportunities and employment choices for girls. in comparison with boys. and cultural norms on the appropriate role for girls within the household.

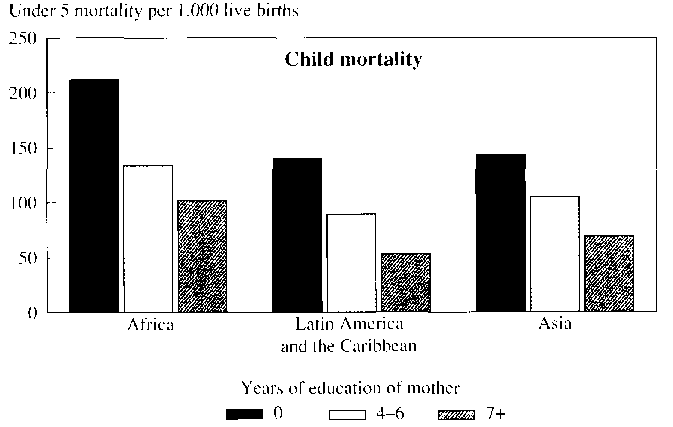

More importantly. the social externalities linked to female education are crucial. Evidence from a large number of countries shows that female education is linked with better health for women and their children and with lower levels (figure 2.2). This link stems from the direct effect of education on the value of a woman's time and consequently. on private returns to her labor. It also stems from the indirect effect of education on the average age at which women marry on their knowledge of basic health care and nutrition, and on reproductive choices (Rosenzweig and Schultz 1982, 1987).

Educating girls and women reduces maternal mortality and fertility rates and increases the demand for health services. A simulation study of seventy two developing countries shows that, with all other factors held constant, a doubling of female secondary school enrollments in 1975 would have reduced tile average fertility rate in 1985 from 5.3 to 3.9 children per household and would have lowered the number of births by 29 percent (Subbarao and Raney 1992. Studies for individual countries have found that one additional year of female schooling can reduce the fertility rate. on average, between 5 and 1 (i) percent (Summers 1994)

Women are more vulnerable than men to micronutrient deficiencies that aggravate poor health (World Batik 1994b). Poor health and nutrition reduce productivity and the chances of reaping gains from investment in education. Intrahousehold inequalities in consumption and nutritional allocations can therefore be a signal of inefficiency Recent estimates suggest that the com effects on morbidity and mortality of just three types of deficiency-in vitamin A, iodine. and iron-could waste as much as 5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), yet correcting these deficiencies would cost less than 0.3 percent of low-income countries' GDP (World Bank 1994c, pp. 50-51). Studies of women tea producers in Sri Lanka and of women workers in Chinese cotton mills document the reduction in productivity associated with iron deficiencies and the positive effects of in-on supplementation on work and output (Edgerton and others 1979). A study of six villages in Andhra Pradesh, India, found that disabling conditions caused by malnutrition and the prevalence of diseases reduced female labor force participation by 22 percent (Chatterjee 1991).

Physical anti mental abuse can also have deleterious effects on the well-being and productivity of women (table 2.1). Violence against women is widespread in all cultures and cuts across all age and income groups Its consequences. include unwanted pregnancy. infection with STDs, miscarriage partial or permanent disability. and psychological problems such as depression anti low self-esteem. Recent World Bank estimates indicate that in both industrial and developing countries domestic violence and rape cause women of reproductive age to lose a significant percentage of really days. Domestic violence appears to be an example of how the relatively weaker bargaining power of women and the paucity of options for them outside the home can affect the intrahousehold distribution of welfare.

Violence against Women Starts in the Womb and Continues trough Life

Table 2.1 Violence against women through the life cycle

|

Phase |

Type of violence |

|

Pre birth |

Battering during pregnancy (emotional and physical effects on the ottoman) effects on birth outcome |

|

Infancy |

Female infanticide: emotional and physical abuse |

|

Girl hood |

Sexual abuse by family members and strangers: forced child prostitution |

|

Adolescence |

Dating and courtship violence: economically coerced sex: sexual abuse in the workplace: rape: farce prostitution and trafficking in women |

|

Reproductive |

Coerced pregnancy: rape: abuse of women by male partners: down abuse and murder partner homicide psychological abuse sexual abuse of unmarried and childless women: abuse of women with disabilities |

Source: Heise 1993

Prospects for gainful employment. as well as the availability of basic social services such as water supply and sanitation. also influence women's well-being. The survival chances of female children in India appear to increase as the employment rate for women rises and the earnings differential between men and women decreases Battilan 1988 Dowry and marriage practices. along with household ownership of land are closely linked to women's chances of survival The effect of such practices cannot be over late. Sen's (1990) comparison of female-male mortality rates in China. India. and Sub-Saharan Africa suggest that more than 100 million women are "missing"

Public spending on social services affects the ability of individuals and households to benefit from their own private spending on human capital. In most industrial countries mortality rates decreased even before modern medical care became widely available, mainly because of improved water supplies and sanitation. The same is likely to hold for the developing world. Public interventions that address market under provision of water and sanitation facilities and shortages of health set-vices such as immunization and family planning-have a significant effect. and one that is probably greater for women than for men.

Lack of data makes it difficult to evaluate the effects of public spending on the educational attainment and health of women and men Very little empirical evidence in this area exists, but there is some indication that the proportion of public subsidies for education that benefits females is lower than the proportion that benefits males. In Kenya in 1992-93. for example. public spending on education amounted to the equivalent of an annual subsidy of 605 Kenyan shillings per capita: males received. on average. 670 shillings and females only 543 shillings. In Mexico the gender difference in public education subsidies was somewhat less: in Pakistan males received almost twice the female subsidy. Gender inequalities in the distribution of subsidies are greater at high than at primary levels. In Pakistan girls receive, on average. only 96 rupees a year for secondary school bag. compared with 58 rupees for boys. Box 2.2 explains how these figures are calculated.

Supply-side differences are partly a function of poorly targeted resources (as. for example, when more is spent on tertiary than on primary schooling). More importantly. they reflect differences in household demand for education for girls and boys. If more girls attended anti stayed in school. the proportion of public subsidy going to girls would he greater.

In health care assessing the incidence of public spending by gender is particularly difficult because of the marked differences in the health needs of women and men. These differences are related to different biological re

The main advantage of this type of analysis is that it measures how well public services are targeted to certain groups in the population, including women, the poor, and residents of regions of interest. Requirements anti to women's reproductive and childbearing roles. Some evidence suggests that because of these differences. per capita health cat-e subsidies to women are the same as and sometimes larger than those to men What is clearer is that women are less likely than men to seek health care. including in many countries. hospital care when it is netted and ate mote likely to consult a non medical health cat-e worker (lather than a qualified medical practitioner). Education tends to increase the likelihood that women will seek health care. whether public or ace the likelihood that women will seek health care. whether public or private (World Bank 1994b).

The importance of private and public investments in education and health services that will improve women's well-being is cleat. These services at-e also important for another season: these is important evidence that increases in women's well-being yield important intergenerational benefits and productivity gains in the future World Bank Living Standards Measure Study (LSMS) surveys car-tried out in Nicaragua (1993 Viet Nam 1993) Pakistan (1991), and Cote (1988) suggest that the probability of children being enrolled in school increases with their mother's educational level and that (controlling, for income and household size) girls. particularly those in non poor households. are mote likely to attend school if their mothers attended school. Other studies show that households with educated mothers lend to provide children with greater quantities of mote nutritious food often at a lower cost. than households with poorly educated mothers (Thomas 1990b)

Data from Brazil show that giving women more control over nonlabor income has a larger impact on child measures, nutritional intakes, and the proportion of the household budget devoted to human capital inputs than if men had control of this income (Thomas 1993) Other studies indicate that women spend proportionately mote of the income they control on health care for children than do men. Women also spend more on food products (as opposed to such goods as alcohol and tobacco) than men do (Duraiswamy 1992: Hoddinot and Haddad 1992) But fathers education is also important especially in interaction with mothers' education (Thomas 1990a)

Other studies have shown that children's educational attainment is lowest in households whet-e the male head has no schooling In Ghana the impact of a mother's education on her children's schooling is reduced when their father has no schooling. even after controlling for income and household size (Lavy 1992).

Material health (which is linked to education) also has important intergenerational effects. Children of mothers who are malnourished or sickly or receive inadequate prenatal and delivery cat-e face a greater risk of disease and premature death. Iodine-deficient mothers run a greater risk of giving birth to infants with severe mental retardation and other congenital abnormalities than do healthy mothers. Reduced fertility and improved health for women can increase individual productivity and improve family well-being. When good health is combined with education and access to jobs. the result is higher rates of economic growth.

The link between the household and the labor market is particularly important. Specialization of labor within the household-whether individually chosen. socially determined. or legally induced-can accentuate gender inequalities in the formal and informal labor markets by leaving most of the unpaid work to women. This situation arises from convention rather than from comparative advantage Inadequate public and community services. transport. and housing also often have an uneven effect on the way men and women spend their time and can increase the demand for goods produced at home using unpaid labor (Moser 1994) Thus women may spend its much (or more time on unpaid work as on market work. In some countries this unpaid work contributes as much as one-third to the economy recorded GDP-and even mote to the welfare of poor families.

The amount of time women contribute to household production and maintenance, direct income generation. and family care combined is widely held to exceed that of men Analysis of data from Bangladesh. Botswana. Ghana. Kenya. Pakistan. the Philippines. and Zambia on how rural women spend their time confirms that, although use of time by women, and by different generations of women varies according to location. available technology. household characteristics. and cultural norms. gender bias in time use is widespread.

Women are generally responsible for collecting fuelwood and carrying water. Girls and alder women often do most of this work, although cultural norms in some countries affect women s mobility. The amount of time allocated to these activities is influenced by seasonal patterns of agricultural activity. the availability of substitute goods and services. and environmental changes. A study in Nepal, for instance, found that deforestation associated with a 75 percent rise in the time per trip would increase the time spent gathering fuelwood by 45 percent for all adults and by 50-60 percent for women.

In addition to fuel and water collection, child care is another activity that dominates women s time-although. considering the importance of children to future household welfare, the amount of direct time spent with children is limited. The seven-country study suggests that more time is spent on child cat-e in female-headed households. Female-headed households tend to have high dependency ratios and relatively large numbers of children, Implying more child-care time overall, but not necessarily on a per child basis. (Kumar and Hotchkiss 1988).

When a large proportion of women's use of time goes unrecorded the design of projects and policies can yield false evaluations of costs and benefits. For example, women's unpaid work may be assumed to have zero value. As a result, women's response to changing incentives may be predicted as being higher than their time constraints actually allow. Project benefits-such as the time saved by locating piped water close to homes or by expanding rural electrification-may also be undervalued. Conversely, the benefits of treeing up time may be far more significant than might have been thought. A study in Tanzania, for example. shows that relieving certain time constraints in a community of smallholder coffee and banana growers increases household cash incomes by 10 percent, labor productivity by 15 percent, and capital productivity by 44 percent (Tibaijuka 1994).

Unpaid work and family responsibilities. as well as lack of investment in women's education. are strongly associated with women's relatively low rates of participation and their limited earnings in formal sector labor. Women's participation rates usually dip in the childbearing years, and earnings tend to decline following an interruption in employment. Younger on average, work more hours than older women, and married women with young children tend to work less than childless women and mothers of grown children. The correlation of marriage and childbearing with labor market outcomes can be seen even in industrial countries, where wage differences between married women and men are larger than those between single women and men Similarly, in some developing countries relative earnings decline with age (table 2.2) Children are not the only treason for interruptions in women's labor force participation; caring for ill or aged family members is often a womans responsibility. A study from Hungary estimates that half of all absenteeism by women workers is the direct result of the need to care for sick relatives (Einhorn 1993).

In Countries, Single Women Earn More Than Married Women and Younger Women More Than Older Women.

Table 2.2 female-male earnings (adjusted for hours worked) by marital status and age (percent)

|

Country |

Female-male |

Earnings ratio |

|

By marital status |

Married |

Single |

|

Australia |

69 |

91 |

|

Austria |

66 |

97 |

|

Germany |

57 |

103 |

|

Norway |

72 |

92 |

|

Sweden |

72 |

94 |

|

Switzerland |

58 |

94 |

|

United Kingdom |

60 |

95 |

|

United States |

59 |

96 |

|

Age |

A 25 |

B 45 |

|

Brazil |

75 |

63 |

|

Colombia |

94 |

70 |

|

Indonesia |

81 |

60 |

|

Malaysia |

82 |

61 |

|

Venezuela |

92 |

70 |

Sources: Blau and Kahn 1992 Sedlacek Gutierrez. and Mohindra 1993

Thus. women s labor market outcomes can be substantially poorer than those of men because women's employment opportunities are constrained by social arrangements at the family or household level. These social demands are reinforced by legal conventions. Within the labor market itself, social or employer discrimination can affect women and men differently. and these differences are reflected in the resource allocation decisions taken within the household. Although wage discrimination is illegal in many countries, employers may respond to an increase in the supply of workers by segregating jobs by gender or offering less training to women who they perceive as being temporarily attached to the labor force (even if in fact most women never drop out). For example, women in the former Soviet Union are fairly well educated and have high labor force participation. but they are concentrated in occupations requiring fewer skills and less vocational training than men, and, on average. they earn less than men (Fong 1993).

Female Wages Are Lower than Male Wages, but This Is Changing.

Table 2.3 female-male earnings ratio over time Female-male earning 1 ratio (percent)

|

Country |

First observation |

Second observation |

A v Average annual percentage change |

||

|

Brazil |

50.2 |

(1981) |

51.6 |

(1990) |

0.7 |

|

Colombia |

67.2 |

(1984) |

70 2 |

(1990) |

0.7 |

|

Côte d'Ivoire |

75.7 |

(1985) |

81.4 |

(1988) |

2.4 |

|

Indonesia |

55.6 |

(1986) |

60.0 |

(1997) |

1.3 |

|

Philippines |

70.9 |

(1978) |

80.0 |

(1988) |

1.2 |

|

Thailand |

73.5 |

(1980) |

79.8 |

(1990) |

0.8 |

Note: Monthly earnings for Indonesia and Thailand rural and urban: for all others urban only

Source: Tzanntors 1995

Women's earnings relative to men's tend to increase over time. A study of six developing countries shows that female earnings relative to male earnings increased by 1 percent a year in the 1980s (table 2.3). There were two reasons for this increase: over the years women entered higher-paying sectors. and within sectors, their pay increased in relation to that of men. This gain would have been even greater had it not been for the effect on wages of increased female participation in the labor force. However, the most visible dimension of gender inequality in the formal labor sector remains the wage difference between men and women. Women's wages are. on average lower those of men by about 30 to 40 percent.

Social or employer discrimination can affect women and men difference and these difference are reflected i/? the resource allocation decisions taken within the household

A recent study of the gender wage gap in Russia shows that after controlling for education differences, the ratio of women's to men's average hourly earnings stands at just over 71 percent: it has remained at that level since the 1960s. Part of the reason for women s lower hourly earnings in Russia and many other countries lies in patterns of occupational segmentation by ,gender. Some analysts argue that women-who do most of the household work in Russian households and also have high participation in the formal labor market cope with the burdens imposed on them by taking less demanding work and devoting less time to advancing their careers (Newell and Reilly 1994).

One difficulty analysts face in interpreting trends in women's labor force participation and employment in developing economies is the large number of women engaged in informal sector activities, many of which overlap with subsistence - orientated household or community-based activities. Informal sector employment in most developing countries. whether in microentreprises or in casual work, is an important source of livelihood for women and their households.

The L competitiveness of women's informal sector activities is constrained by women's limited mobility and lack of access to financial and public sectors.

A recent study in Mexico estimates that 41 percent of the work force in Mexico's major-cities is employed in the informal sector (World Bank 1995c). Data from a 1989 survey show that 60 percent of men working in the sector are salaried workers' compared with only 18 percent of women. By contrast. 80 percent of women working in the sector are unpaid family members, as against 27 percent of men. By far the most common activity in the informal sector is commerce (fixed-location or itinerant), followed by repair works food preparation. and sales, and small-scale manufacturing. The sectoral distribution of informal employment reflects the hey role informal workers play in supplying goods and services to low-income consumers. Women tend to be concentrated in commerce and men in services and manufacturing, although the percentage differences are relatively small. Two generalizations can be made on the basis of this study: informal sector workers earn less than workers in large firms and women earn less than men.

Another recent study of tour communities in Lusaka. Guayaquil (Ecuador), Metro Manila, and Budapest shows that informal sector activities ate especially important for during periods of economic reform Although the numbers both of men and of women in the labor force tend to increase during these times women rely more on the informal sector than men clot The competitiveness of womens informal sector activities is informal by women's limited mobility and lack of access to financial and public services. Women also tend to specialize in non traded goods and services that show relatively low average returns to labor. Across the tour cities in the study, women earn between 46 and 68 percent of men's wages (Moser 1994)

The ability of informal sector workers to increase their returns depends on access to physical and human capital and their relationship to the institutional and regulatory environment. Contrary to the common belief, many microenterprises face considerable costs associated with the regulatory environment, including registration and licensing fees, as well as outlays for contracts with public authorities concerning zoning regulations and use of public utilities. In Argentina regulatory costs are estimated to absorb as much as 21 percent of the average microfirm's operational expenses. In some sectors, such as manufacturing and construction, the costs of regulation are about 44 percent (World Bank 1994d). In Mexico real regulatory costs. including the costs of compliance and evasion, are about 20 percent of total costs.

Regulatory costs also inhibit Job creation in the informal sector. In Argentina across-the-board deregulation could generate as many as 170,000 jobs in small-scale manufacturing alone. Furthermore. poor workers in family-based firms or micro enterprises and particularly women entrepreneurs-often lack access to such basics as water and power. Targeting infrastructure investments to the poor, which takes account of the needs of women entrepreneurs s. can significantly enhance their productivity and earnings.

In rural area where formal markets often are not well developed. informal employment activities play a vital role. In Asia the proportion of female rural wage laborers increased sharply in the 1960s and 1970s. In India women make up a larger proportion of rural wage laborers than of the entire labor force, probably because of growing landlines and poverty among rural households. Rural household labor accounts for a disproportionately large share of employment among the poor and an even larger share among women. Furthermore, a larger proportion of female than male laborers are hired on a casual basis, largely because family arrangements, especially lack of control over property, limit women's ability to work (Hart 1986: Bardhan 1993). Low status in the labor market is also linked to low female indicators in education, health, and nutrition.

Providing credit directly to women has a positive effect on household and individual welfare and improved gender equality.

Social norms affecting decisions within the family about occupational choices or migration can also lead to differential patterns of male and female earnings in informal markets (Bhiswanger and Rosenzweig 1984). Family responsibilities hinder women's geographic mobility, constraining their ability to command high wages and limiting them to certain areas or industries. The concentration of women in certain sectors, especially nontraded goods and set-vices. intensifies competition between women entrepreneurs and wage workers and lowers the returns to female labor. These effects are compounded by women's lack of access to credit. training, and technology.

(fender Inequality in Access to Assets and Services )

The availability of financial services and access to them are considered important for several reasons. First. savings provide a kind of self-insurance. Second, credit helps households maintain a certain level of consumption at those times when their income fluctuates temporarily. Third, credit can be used to fund investments in capital or other inputs that will yield relatively high returns to production. if households cannot finance such investments from their own savings. A fourth and no less important reason is the role of savings and credit in increasing household members' options outside the home.

Inequalities between women and men in access to financial services- particularly credit--are widely documented. Collateral requirements, high transaction costs. limited mobility and education, and other social and cultural barriers contribute to women's inability to obtain credit (Holt and Ribe 1991). The implications tot household efficiency and individual well-being differ, however, depending on whether the household pools its financial resources. If, as the unitary household model assumes. a household pools its resources the characteristics of individual borrowers are less important than if there is little or no pooling. In the first case. credit resources will be used to meet household needs that have been jointly determined, regardless of who the borrower is. In the second case, the use credit is put to and the needs it then satisfies depend on which household member is borrowing.

A recent study of credit programs in Bangladesh sponsored by the World Bank shows that providing credit directly to women has a positive effect on variables typically associated with household and individual welfare and improved gender equality (Pitt and Khandker 1995). The study looks at three programs in Bangladesh: the Grameen Bank. the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), and the Bangladesh Rural Development Board (BRDB). in 1992, women accounted for 94 percent of Grameen Bank members. 82 percent of BRAC members. and 68 percent of BRDB members (Khandker and Khalily 1995; Khandker, Lavy, and Filmer 1994). Only the results for the Grameen Bank are presented here.

Table 2.4 presents the impact of credit obtained by women and men on a variety of social and economic indicators. The results show a clear and positive impact of both male and female borrowing on all indicators of Toward gender equality family welfare especially through an increase in per capita expenditures increases in both boys' and girls schooling, anti a reduction in fertility. Females borrowing has a greater effect on girls' schooling anti per capita expenditure than does male loot-rowing: male borrowing has a greater effect on boys' schooling and fertility than does female borrowing. Interestingly. female borrowing also results in mote female ownership of nonoland assets and an increased supply of female labor to cash - income -earning activities (Pitt and Khandker 1995).

Loans to Women and Men Have Important Welfare Implications.

Table 2 4 welfare effects of Grameen Bank loans (percentage increase)

|

Welfare e change |

Effect of male borrowing |

Effect female borrowing |

|

Increase in boys' schooling |

7.2 |

6.1 |

|

Increase in girls schooling |

3.0 |

4.7 |

|

Increase in per capital expenditure |

1.8 |

4.3 |

|

Reduction in recent fertility |

7.4 |

3.5 |

|

Increase in women's labor supply to cash-income earning activities |

0 |

10.4 |

|

Increase in women nonland assents |

0 |

19.9 |

The introduction of programs such as the Grameen Bank in a village has a positive effect on agricultural and nonagricultural production (Khatidketati Chowdhuty 1994: Rahman and Khandke 1994 The probability that women will be self-employed rather than work for wages increases by 52 percent. The latter finding is important because much of the wage employment open to women in rural areas is very poorly remunerated and can be quite exploitative. Self employment can bring the opportunity of higher returns for women, plus the freedom to integrate their earning activities into other work as they see fit.

Access to financial services alone cannot reduce gender inequalities in the allocation of household resources. A qualitative study reviewing several targeted credit programs in Bangladesh cautions against overgeneralizing about the benefits of giving women access to credit. The study finds that it is difficult to infer that increased borrowing alone improves women's bargaining power because in many rural Bangladesh households the question of who controls the resources is quite complex (Goetz and Sen Gupta 1994). Nevertheless. the possibility of receiving credit (or similarly of working for wages) may give women greater bargaining power within the household. This bargaining power can be used to improve child health and nutrition and may increase the likelihood that children will attend school.

The ownership of land and the distributions of land rights influence the productivity of labor and capital resources and the incentive to invest in resource management Private property rights. in particular. are associated with increased access to product and factor markets. especially credit markets. and to public services such as public utilities and agricultural extension. However. relatively little direct evidence exists to link independent owner of land by women with increased access and productivity. One obstacle to empirical work is that women s access to land and property is often mediated trough marriage (A married woman land rights are frequently limited to use rather than ownership.) Future more. complex systems of land tenure make it difficult to generalize about the effects of owner ship on productivity. None some evidence suggests that independent land rights for women could enhance both the efficiency with which resources are used and the well-being of women and their households: (Agarwal 1994).

The possibility of receiving credit may give e women greater bargaining power within the household which can be used to improve child health and nutrition.

While independent land rights may increase efficiency and household welfare, lack of secure land appears to be associated with low investments by women in land conservation. In Zimbabwe's communal areas, land that a women acquires is often allocated to her only temporarily: for example, the location of land allotment received from husbands or borrowed from neighbors is usually subject to periodic change (Jackson 1993). The same is true in parts of West Africa (David 1992 Jackson 1994). Uncertainly about the permanence of their control over the land means that women may be reluctant to invest in improvements that will benefit the landowner rather than the user.

A significant trend in recent decades in developing countries has been the move toward private ownership In some countries this trend has been encoulagecl by reforms dealing with land redistribution tenancy or land titling Such reforms are considered important for promoting long-term investments and the adoption of the latest technology They also provide the collateral people need to gain access to credit and other factor markets Ironically, evidence also suggests that perform inequalities in male and female land rights are reinforced by land reform programs For example, in Latin America most reforms are based on the premise that the man of the household its the household head. This presumption means that women (except for widows and ownership. Even where women and men benefit equally from land reform differences exist between nominal and real land rights (see box 2.3).

In the central part of European Russia and in Moldova the lands and assets of state and collective farms are being parceled out in allotments as part of wider economic reforms. Every person who lived and worked on a collective farm receives a share of the land Data show that although on average, women have received a slightly higher proportion of land shares than men, the nonland capital assets of the old farms ale being distributed as property shares on the basis of a formula heavily weighted toward an individual's wage rate and years of employment. Such criteria favor men over women and give men more valuable property chares. Dividends paid on these property shares also tend to be higher than those paid 011 land shares Holt 1995).

Land reform programs that fail to account for gender differences in rights

|

Box 2.3 who gets access to land? Honduras and Cameroon Honduras' Agrarian Modernization Law of 1974 includes a provision giving men age 16 or older the right to access to land, independent of any other qualification. For women. however, this right is restricted to unmarried mothers or widows with dependent children. Furthermore. if a male beneficiary dies or becomes incapacitated. the law gives preference in inheritance rights to a male child over the child's legally married mother. Some 30 percent of rural Honduran households are headed by women at least part time because of the seasonal migration of men to look for work (Saito and Spurling 1992). |

In the northwest and southwest provinces of Cameroon. an estimated 50 percent or more of those who claimed land within the first ten years of land registration (1974-85) were classified as public servants. Over 32 percent of all the remaining land titles went to businesses.

Women make up more than 51 percent of Cameroon s population and do more than 75 percent of the agricultural work. but they are virtually absent from land registers. Only 3.2 percent of all land titles issued in the Northwest Province were given to women; in the Southwest Province the figure was 7.2 percent. For the country as a whole. it is estimated that women obtained under 10 percent of all land certificates (World Bank 1995a). to own. use, and transfer land may actually exacerbate the insecurity of women's land claims and. as a result, harm household welfare. For example, there is evidence that land titling focused on male household heads has adversely affected women's ability to farm independently. Moreover. intrahousehold inequalities in income and decisionmaking have increased (FAO 1993) In Africa some titling programs have allowed men to take advantage of their control over land to redesignate land formerly cultivated by women as household land. This switch provided the opportunity for men to increase the amount of work they expect from women on household plots. In other cases women have received smaller and less fertile plots than they had before for their personal crops (FAO 1993).

Recognizing women's independent claims to land is therefore an important issue in property reform. In poor households. having rights to land could alleviate both women's own poverty and the household's risk of remaining poor. The season is mainly that women s access to economic resources has a positive effect on household welfare (Agarwal 1994). From the point of view of efficiency, secret land tenure increases the incentive to manage resources efficiently and expands access to formal credit markets. Because secure land tenure can mean greater productivity, it may also increase the household's incentives to invest in women's human capital.

Agricultural extension services provide information training and technology to agricultural producers. Extension services have always been regarded as necessary for agricultural modernization. Given the importance of women's labor to agriculture in most regions, providing women with access to agricultural extension services is essential for current and future productivity. Types of agricultural extension services vary, hut in most countries publicly provided services dominate. Evidence suggests that women have not benefited as much as men have from publicly provided extension services.

Given the importance of women's labor to agriculture it is in most regions providing women with access to agricultural extension services is essential for current and future of productivity.

A review of five African countries shows that extension agents are most likely to visit male farmers than female farmers (table 2.5) The impact of this inequity on female productivity depends in part on whether women and men within households pool information. There is, however. little evidence to suggest that this happens (see box 2.4). It is important to ensure that extension services reach omen directly, not only to redress gender inequalities but also to maximize productive efficiency. omen play a critical role in production of food and cash crops for the household. in postharvest activities. and in livestock care Men and omen perform different tasks they can substitute for one another only to a limited extent. and this imitation creates different demands for extension information Also, as men leave farms in search of paid employment ill urban areas. women are increasingly managing and operating farms on a regular and full-time basis. Hence. omen are becoming a constituency for extension and research services in their own right (World Bank 1994e)

Table 2.5 visits by agricultural extension agents (percentage of households visited)

|