Prepared by

Judith Brace

and

Ralph R. White and Stephen C. Bass

Illustrated by

Anne Brace

with special display illustrations by

Kathleen R. Rafferty

A cooperative project, sponsored jointly by Peace Corps

and the National Audubon Society.

Peace Corps

Information Collection & Exchange

Manual M0007

1977

INFORMATION COLLECTION & EXCHANGE

Peace Corps' Information Collection & Exchange (ICE) was established so that the strategies and technologies developed by Peace Corps Volunteers, their co-workers, and their counterparts could be made available to the wide range of development organization and individual workers who might find them useful. Training guides, curricula, lesson plans, project reports, manuals and other Peace Corps-generated materials developed in the field are collected and reviewed. Some are reprinted "as is"; others provide a source of field based information for the production of manuals or for research in particular program areas. Materials that you submit to the Information Collection & Exchange thus become part of the Peace Corps' larger contribution to development.

Information about ICE publications and services is available through:

|

The Peace Corps Internet Web Site address: http://www.peacecorps.gov Please note the new Peace Corps Mailing Address from July 1998 on is: ICE/ Peace Corps 1111 20th Street N.W. Washington, DC 20526 USA |

|

Add your experience to the ICE Resource Center. Send materials that you've prepared so that we can share them with others working in the development field. Your technical insights serve as the basis for the generation of ICE manuals, reprints and resource packets, and also ensure that ICE is providing the most updated, innovative problem-solving techniques and information available to you and your fellow development workers. |

About this manual...

Reply form...

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1: The self-contained conservation education center

Planning

The building

Landscaping

The nature trail

Conservation demonstration area

Outdoor exhibits

Exhibits

Signs and labels

The conservation education center in shared facilities

Source materials - Chapter 1

Chapter 2: Conservation education in a school

A school conservation education outline

1. First Year: Looking at Your Environment

2. Second Year: Change in the Natural World

3. Third Yeah: How Environment Differ

4. Fourth Yeah: Talking Care of Natural Resources

5. Fifth Year: Use of Natural Resources

6. Sixth Year: Responsibility for Environmental Conservation

Conservation science fair

Source materials - Chapter 2

Chapter 3: Conservation education in a health center

Nutrition

Sanitation

Health

Source material - Chapter 3

Chapter 4: Conservation education in an agricultural extension center

Soil conservation

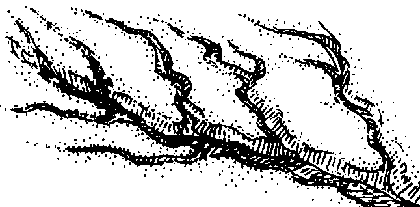

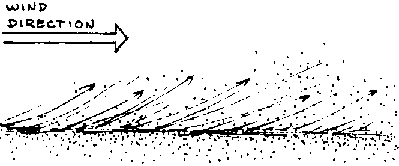

Erosion

Erosion control methods

Results of erosion

Control of nutrient loss

Source materials - Chapter 4

Chapter 5: Conservation education in a community center

Cooperative programs

Leadership training

The community environment

Source materials - Chapter 5

Appendix A: Exhibit and study materials

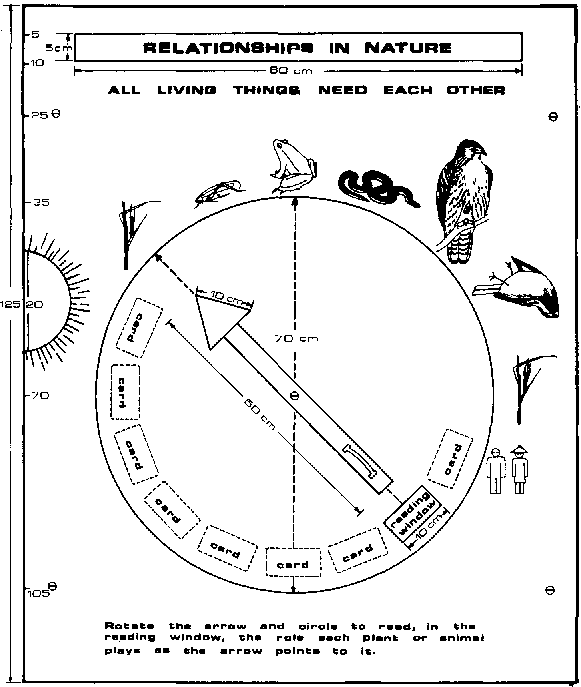

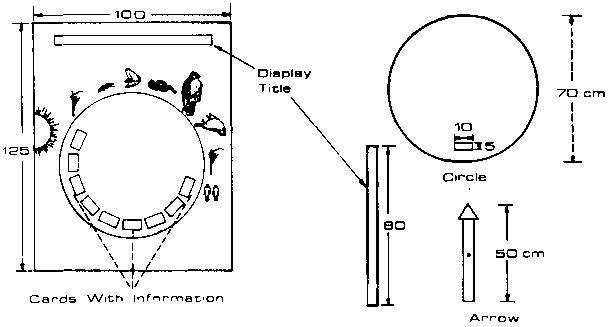

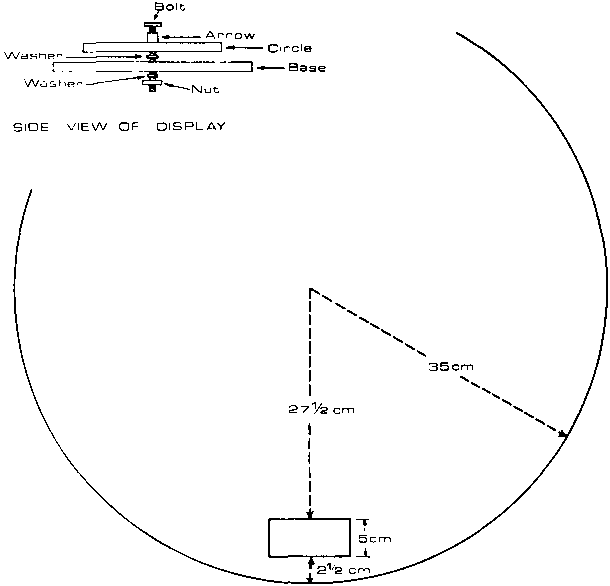

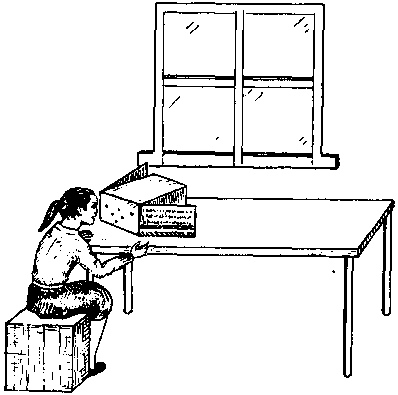

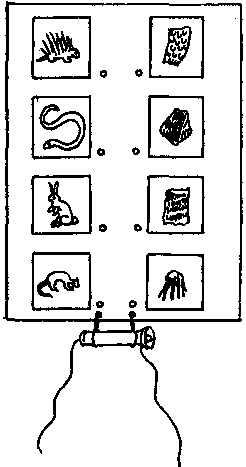

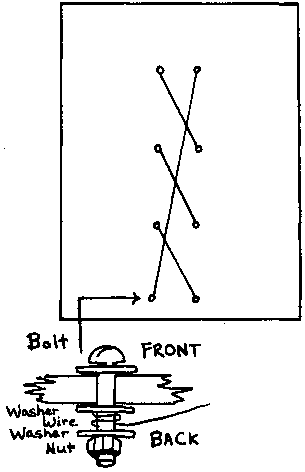

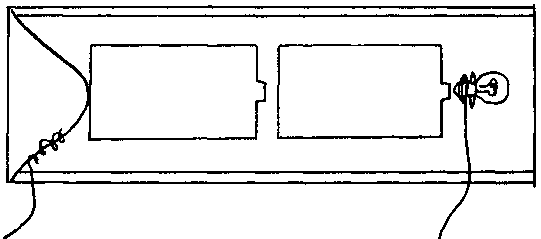

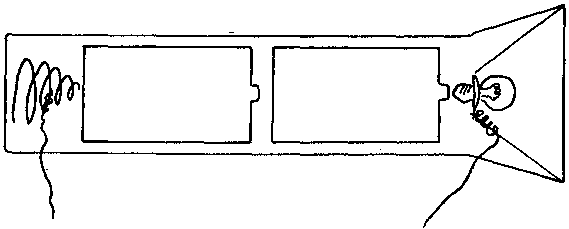

Visitor participation exhibits

Suggested exhibits

Collections for exhibit and study

Visual aids for exhibits

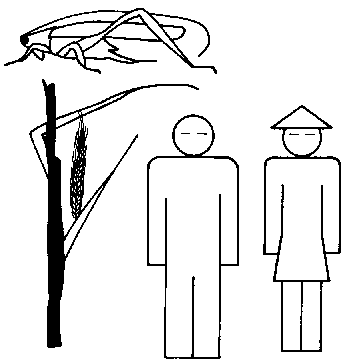

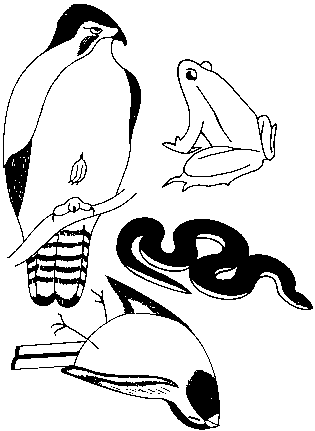

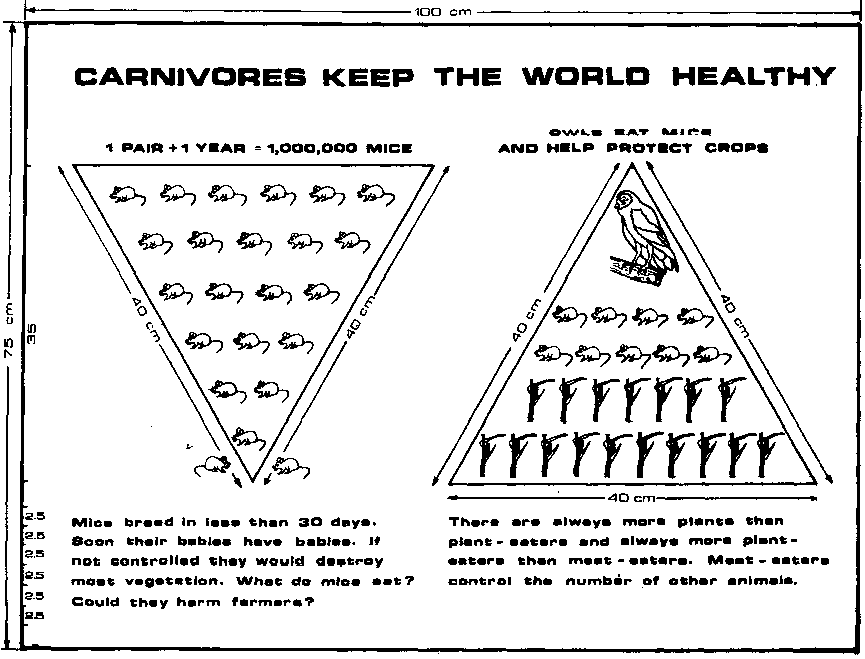

Display poster - Life pyramid/food chain

Introduction to concepts

Concepts about the ecosystem

Concepts about populations

Population poster

Concepts about water, soil and air

Studies about soil

Studies about water

Studies about the sun's energy

Studies about plants

Source materials - Appendix A

Appendix B: Nature Trails

Purpose of a Natural Trail

Characteristic of a Nature Trail

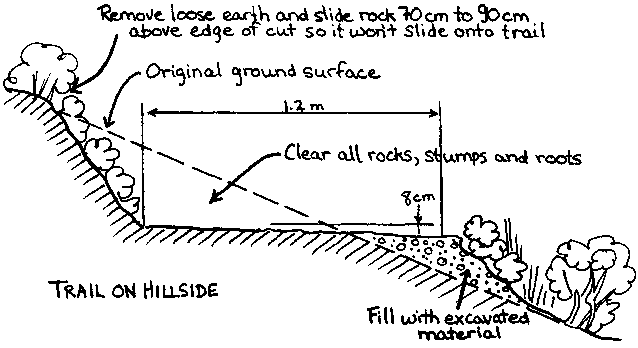

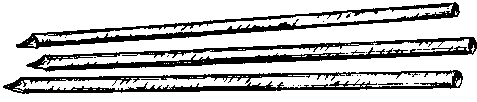

Constructing a nature trail

Features proposed for labeling and explanation along a nature trail in South East Asia

Source materials - Appendix B

Appendix C: Landscaping

Suggestions

Compost

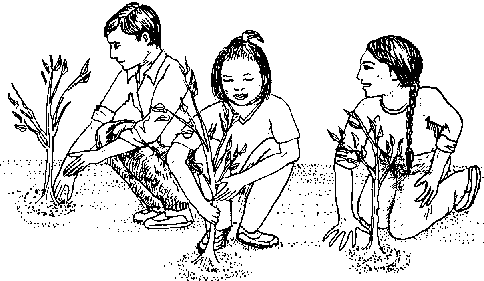

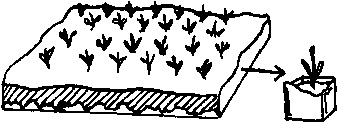

Transplanting

How to select and collect seeds

Growing seeds

Suggested site plan

Source materials - Appendix C

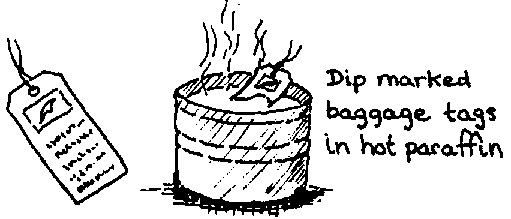

Appendix D: Signs, labels and guides

Signs

Labels

Guides

A suggested nature trail guide for Guatopo national park, Venezuela

Source materials - Appendix D

Appendix E: Public facilities

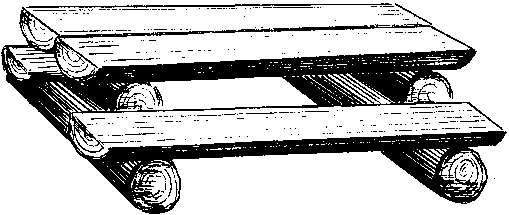

Rest stops

Picnic areas

Latrine facilities

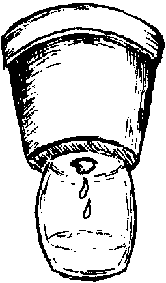

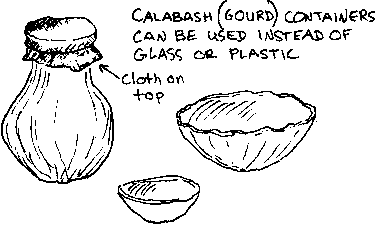

A calabash washstand

Parking

Source materials - Appendix E

Appendix F: Live animals

The collection

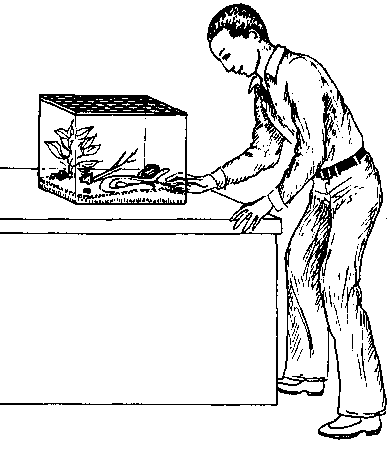

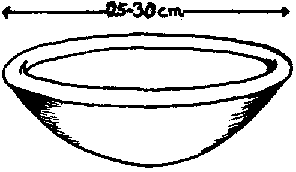

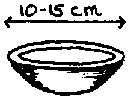

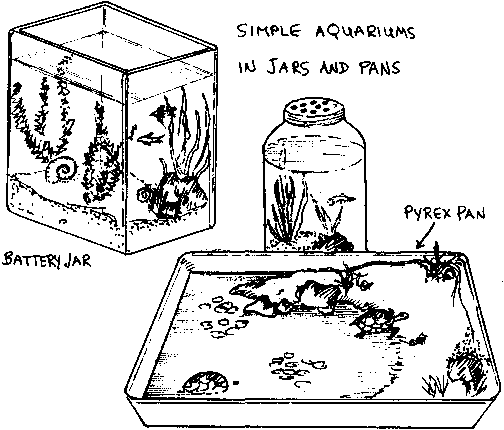

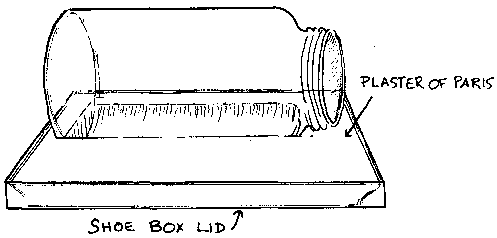

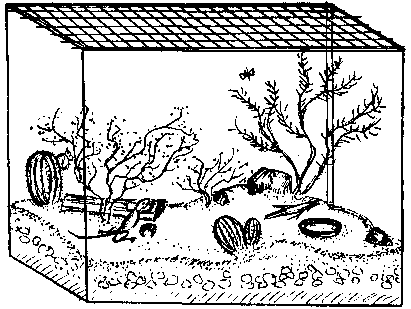

Aquariums

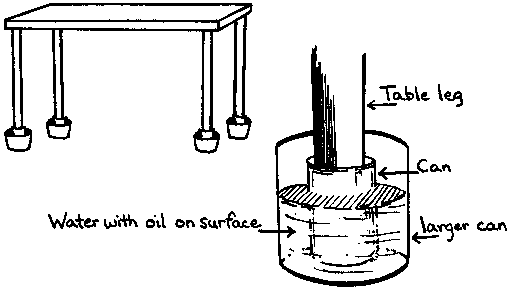

1. A freshwater aquarium

2. A marine aquarium

Terrariums

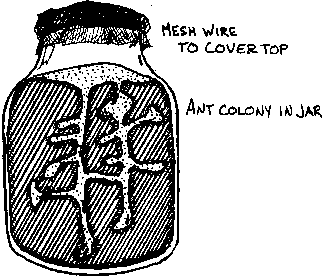

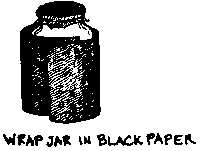

Ants

Earthworms

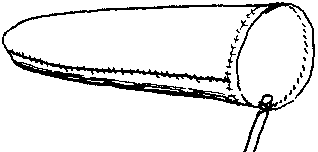

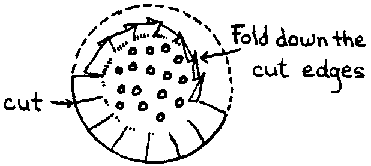

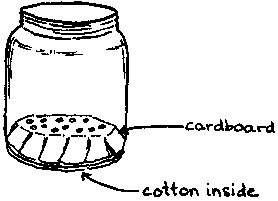

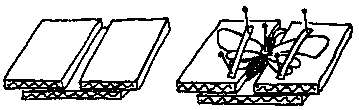

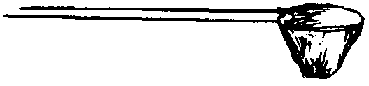

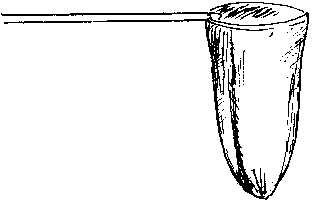

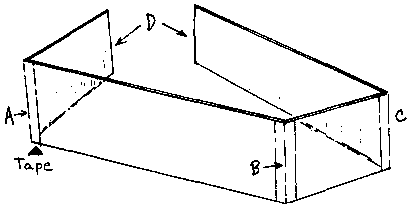

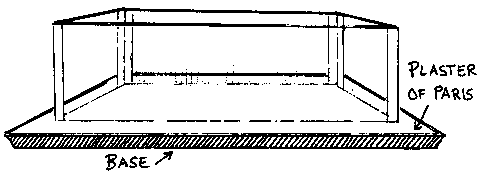

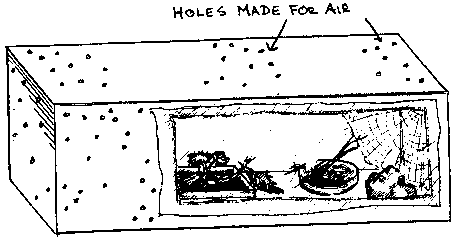

Cardboard insect box

Mammal cages

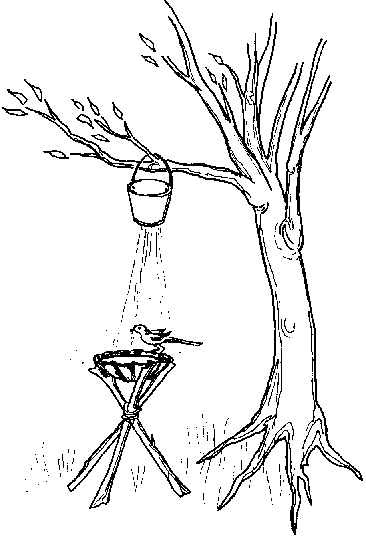

An outdoor bird attraction

Source materials - Appendix F

Appendix G: Endangered species

A school program

A community program

Endangered animals of selected countries

Source materials - Appendix G

Selected organizations concerned with conservation education

Selected environmental research centers

Glossary

Teaching Conservation in Developing Nations is a how-to manual. It is designed as a working tool for Peace Corps Volunteers and other development workers: the suggestions which have been presented for conservation education activities or centers can be adapted as appropriate to any job or setting. The purpose of the manual is to help Volunteers and others to incorporate conservation education into their day-to-day community activities, and to suggest resources for those who choose to become more deeply involved in any aspect of environmental education.

The Preparation of Teaching Conservation in Developing Nations has been a cooperative project sponsored jointly by the Peace Corps and the National Audubon Society. The publication was initially undertaken by Ralph R. White and Stephen C. Bass for the National Audubon Society. Mr. White, while a Peace Corps Volunteer in Thailand, was instrumental in the development of a Nature Education and Wildlife Center for the Royal Thai Forestry Department. He subsequently worked at the National Audubon Society with Mr. Bass, naturalist/planner, and Kathleen R. Rafferty, cartographer/illustrator, to adapt his experience for other centers in developing nations. Their original document was then submitted to the Peace Corps information Collection and Exchange, which undertook to expand and adapt it for broader use, with the assistance of writer/editor Judith Brace and illustrator Anne Brace.

Teaching Conservation in Developing Nations is the seventh manual in the "Appropriate Technologies for Development" series being published by the Peace Corps. Since 1961 Peace corps Volunteers have worked at the grassroots level in countries around the world in program areas such as agriculture, public health, and education. Before beginning their two-year assignments, Volunteers are given training in cross cultural, technical and language skills. This training helps them to live and work closely with the people of their host countries. It helps them to live and work closely with the people of their host countries. It helps them, too, to approach development problems with new ideas that make use of locally available resources and that are appropriate to the local cultures.

Recently the Peace Corps established an information Collection and Exchange so that these ideas developed during service in the field could be made available to the wide range of development workers who might find them useful. Materials from the field are now being collected, reviewed, and classified in the information Collection and Exchange system. The most useful materials are being shared as widely as possible. The information Collection and Exchange provides an important source of field-based research materials for the production of ''Appropriate Technologies for Development" manuals such as Teaching Conservation in Developing Nations.

|

Note to the Reader Due to the high demand for this publication, it has been reprinted without revision (e.g., selected organizations). Updates to the manual are now in progress. - May 1997 |

Contributors...

Judith Brace, co-author of Teaching Conservation in Developing Nations, has written and edited a variety of reports and articles on conservation, environmental planning, and urban affairs. She has also conducted research projects in comparative education in several developing nations.

Ralph R. White served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Thailand, where he worked with the Royal Thai Forestry Department. He subsequently worked at the National Audubon Society, and co-authored the manual, based on his experiences in Thailand.

Stephen C. Bass, who helped to research and co-author the manual, has served as a naturalist/planner for the National Audubon Society Nature Center Planning Division.

Anne Brace, who provided the illustrations for the manual, is currently studying at Scripps College, Claremont, California. Ms. Brace has provided illustrations for a variety of publications; her most recent work is in the field of animation.

Kathleen R. Rafferty, who prepared the special display illustrations for the manual, is a cartographer for the National Audubon Society Nature Center Planning Division.

Many thanks are also due to Brian Bedell and William J. Manly of the National Audubon Society, James A. Sherburne of the Smithsonian institute, and Richard A. Saunier of the inter-American Development Bank, for their technical review of materials in this publication.

For your convenience, a reply form has been provided on the following page. Please send it in and let us know how the manual has helped or can be made more useful. If the reply form is missing from the manual, just write your comments, suggestions, descriptions of problems, etc., on a piece of paper and send them to: CONSERVATION EDUCATION; Peace Corps information Collection and Exchange; 806 Conn. Ave.; Washington D.C. 20525; U.S.A.

PLEASE RETURN THIS FORM

NOTE TO THE USER: This manual was published because the Peace Corps and the National Audubon Society wish to help in an area of growing worldwide interest. In order to provide the most effective help, the preparers of the manual need to know how it is being Used, or how you feel it could better serve your needs. Please fill in the following form and return it to:

Teaching Conservation in Developing Nations

Peace Corps/ICE, 8th Floor

1990 K Street, NW

Washington, DC 20526 U.S.A.

WHEN WE RECEIVE THIS FORM, WE WILL AUTOMATICALLY PLACE YOUR NAME ON A MAILING LIST SO THAT YOU WILL RECEIVE:

*Updates and/or additions and corrections to the manual, as they become available; and

*Notice of other publications which may be of interest to you.

If you have questions on the material presented in the manual, or if you run into problems implementing the suggestions offered here, please note them in the space provided. Use additional paper if you have to, in order to be as specific as you can about the problem. Wherever possible, we will try to provide you with or direct you to an answer.

|

Date |

___________ |

|

Your name |

___________ |

|

Your company or agency, if any |

___________ |

|

Your address |

___________ |

1. How did you find out about the Peace Corps/National Audubon Society Teaching Conservation in Developing Nations manual? How did you get your copy?

2. Which parts of the manual have you found most useful? Least useful? Why?

3. Did you find the manual easy to read, too simple or too complex, complete or incomplete?

4. How has this manual helped your work? What have you done to apply the information?

5. Can you recommend additional information which you feel should be included in a new edition of the manual?

6. What were your successes using the manual or implementing any of the suggestions? Problems? Please describe completely.

7. Do you have other recommendations?

Privacy Act Notice: Furnishing the information requested herein is completely voluntary. It is requested under authorities contained in the Peace Corps Act (22USC 2501 et seq.). The only uses which will be made of this information are as follows: 1) For management purposes involving the format of future issues of this publication; 2) For incorporation in a mailing list for this and other similar publications.

The natural resources of any country---its land, its rivers, its forests, and the like---are crucial to supplying the population with such basic necessities as food, water, and energy.

Unfortunately, human activities, particularly in the sectors of agriculture and forestry, often involve the destruction of these resources. Clearing of land for grazing and crop production, when followed by over-grazing oh improper agricultural practices, leads to a never-ending need to clear more, and often less stable, land. Such overutilization and deforestation of land (especially if combined with a rapid increase in human population and the demands that accompany such an increase) destroys the ecosystems necessary to human survival, silting up rivers, destroying watersheds, rendering soil unproductive, and ultimately leading to famine and the spread of disease.

This does not mean that land should not be developed to meet basic human needs. What it does mean, however, is that there is an immediate need to balance planning for development with conservation practices. Reforestation, rotational grazing, management of domestic herds, watershed management, development of alternative protein and renewable energy sources, improvement of sanitation, and wildlife management are a few of the ways in which natural resources can be used wisely or restored.

Before people will accept any of these methods as necessary, however, they must have an awareness of the environment and an understanding of the reasons for conservation of natural resources. This manual, it is hoped, will provide Peace Corps Volunteers and other field workers with ideas, activities, and resources for incorporating conservation education into their day-to-day community activities. For awareness and understanding stimulated by conservation education can lead to interest, participation, and, hopefully, action on the part of people who are becoming more and more dependent upon the sound use of their own natural resources.

James A. Sherburne

Program Manager

Smithsonian/Peace Corps Environmental Program

People will not preserve and protect a natural environment which they do not understand or respect. When people learn about the relationship of all forms of life to each other and to the earth, they begin to have a responsible attitude toward natural resources and their wise use.

The goal of conservation education is to lead the public through a series of steps about nature, land and natural resources. These are:

- awareness

- understanding

- respect

- responsibility

- action

The purpose of this manual is to show that conservation education can be presented in a variety of ways and in a variety of situations, and that there is no single method of presentation. The ideas which are presented here are to stimulate your own ideas which will relate to your own situation. It is generally easier if you have a physical setting such as a government building, a school, a community or other local center in which to present an on-going conservation education program by means of pictures and posters, exhibits and collections, films and discussions. This manual has been structured around this kind of setting.

The manual begins with a Chapter dealing with a self-contained conservation education center in order to give you the broadest possible range of ideas that could be used in presenting conservation education. Although you may not be planning this sort of center, as you read the Chapter look for general ideas which you could use in other ways. The Chapters which follow tell of ways in which a conservation education program can be incorporated into your activities if you are working in a school, a health center, an agricultural extension center or other community services. Again, as you read these Chapters, look for ideas you can use. The Appendices help you to carry out specific suggestions which are presented in the Chapters; at the end of the manual there is a list of places which can provide you with further information, and a Glossary of the environmental words used in the manual.

Do not feel that it is necessary to have a formal setting in order to educate people about their environment. If you are a community leader, or a health or agricultural extension worker who visits several communities, you will find that many of the ideas presented in the manual can be adapted for informal presentation in your situation. If you are a school teacher, use the portions of the school conservation education program (Chapter 2) that are suitable to the needs of your school's community.

What is important is to start people thinking about how to improve their own lives by improving their natural environment. In addition to the ideas suggested in this manual, you might prepare a short daily message to be presented on the local radio to encourage people to start thinking about the practice of erosion control as a means to reduce crop loss (see Chapter 4). Or you might prepare a short weekly feature in the newspaper to tell which local animals are endangered, and why (see Appendix G).

All of these are ways to help you develop your community's interest and responsibility toward the environment. If you can bring an understanding of environmental interdependence to Just one area of community life, you have made a contribution to conservation as a whole.

A full-scale conservation education center consists of an interpretive building for visitors and an area of natural land with a trail for nature study.

The advantage of a full-scale conservation education center is that the entire facility can be planned around the directly visible and accessible characteristics of the local environment. Indoor exhibits explain and expand on what is seen out-of-doors. The outdoor trail demonstrates in a natural setting the interaction of the grasses, flowers, trees, fish, birds, insects, reptiles, mammals and geological features found there.

This kind of conservation education center aims for a complete presentation of the local environment and will include concepts which reflect the various specialized relationships of the region. If, for example, lack of water is a major environmental factor, study can focus on the inter-related effect this has on the soil, on the adaptation of plant and animal life, and on health and food problems.

If you are planning a full-scale conservation education center, you are probably working with a government agency and will have the technical assistance as well as financial support necessary for this major effort.

The land selected for use by the conservation education center will probably be part of an existing reserve of government land. If possible, considerations in the selection of the center's site should include:

1. ease of access by visitors;

2. variety of land features: water, open space, wooded area, land formations;

3. variety of wildlife population.

A desirable minimum site size for a full-scale center is 10 hectares. If a conservation education center is being considered within a city's limits, and a site this large is not to be found, it may be possible to use several smaller sites with each section assigned a different conservation education use.

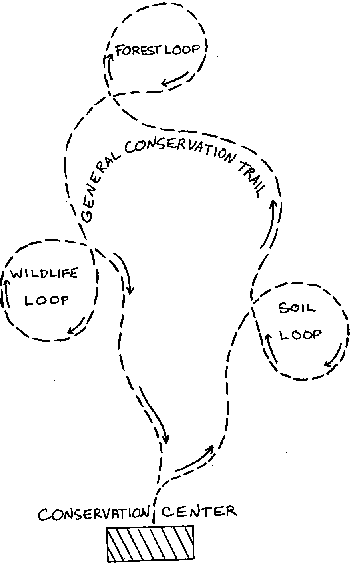

Your site layout should be the result of careful preliminary planning to determine the kind of facilities you will offer. Will you be visited by school classes, by people in buses or cars, by hikers or picnickers? Will the nature trail be for general study only or will you want to include additional smaller trails which study a single feature, such as geology?

In its broadest form, a conservation education center could include not only the interpretive building and trail, but also a small-scale farm or natural resources management area where government technicians could demonstrate effective conservation practices for agriculture, such as:

|

Soil conservation practices |

Compost pile |

|

Forest management practices |

Crop storage |

|

Reforestation |

Well with pump or windlass |

|

Small vegetable garden |

Smoke house |

|

Pond for fish cultivation |

Honey bee hive |

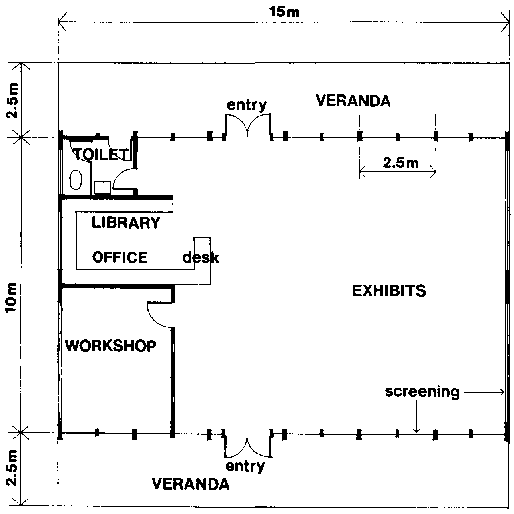

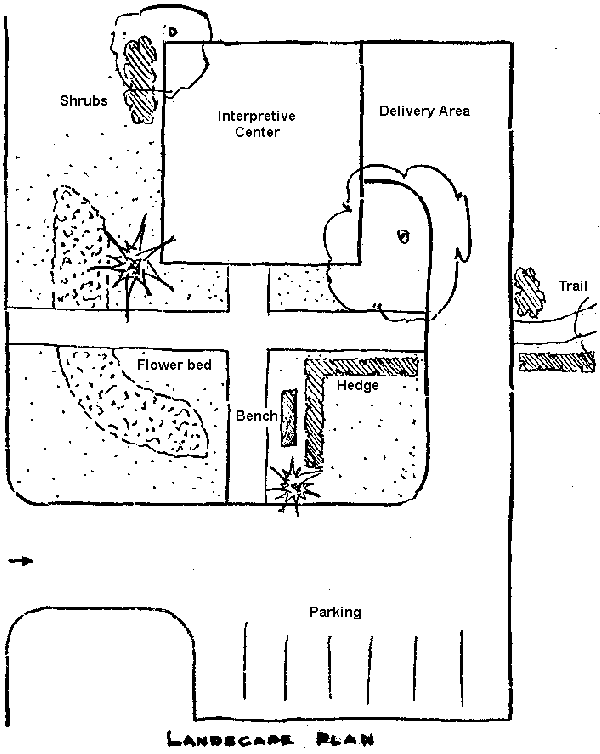

Once you have decided what the conservation education center will provide for its visitors, you can then make a site plan to place each facility in the most desirable spot.

The Nature Trail (See Appendix B. Nature Trails) should link the most interesting natural features of the site.

The Interpretive Building should be located at the point of departure and return of the nature trail loop.

Picnic, Latrine and Parking facilities (see Appendix E, Public Facilities) should be located near the interpretive building.

Wherever facilities are provided, make it a point to do as little damage to the site as possible. Plan carefully to avoid cutting trees, to avoid excess earth-moving, to avoid unnecessary destruction of ground cover. Practice conservation techniques to reduce erosion, such as re-channeling water drainage, filling depressions with stones or gravel, rebuilding worn-away banks and planting ground cover.

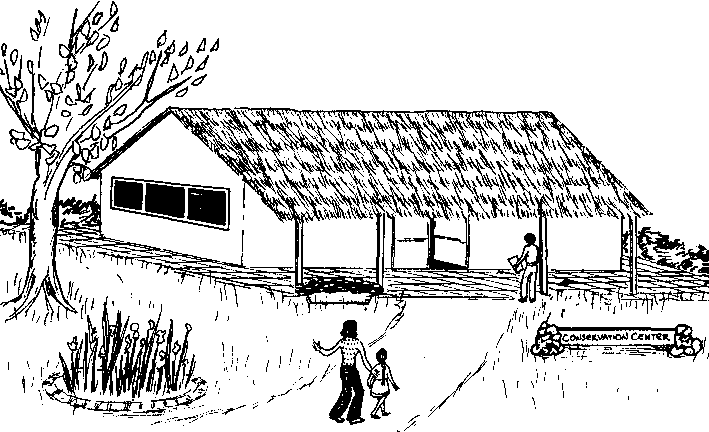

In planning the building you must decide what kind of indoor facilities you will be able to offer. The basic need is for an interpretive room where the exhibits are located. The interpretive space should be large enough that you can use it for a group meeting room, or for showing slides or films, if these are available from a government service.

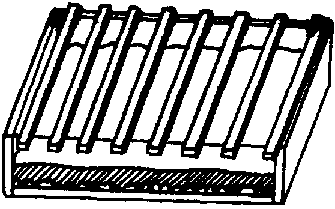

Wall space can be Used for graphics, posters and hanging exhibits; counter tops can hold collections, aquariums or terrariums. Cabinets can provide storage for alternate exhibits and materials which might be loaned to schools.

Will you be able to provide office space for the center's staff? Can you provide a small laboratory for staff use and student training? Can you provide a small library where conservation books, magazines, photographs and other resources could be made available to the public? Can you provide a workshop for preparation of exhibit and interpretive materials? Can you provide indoor toilet facilities?

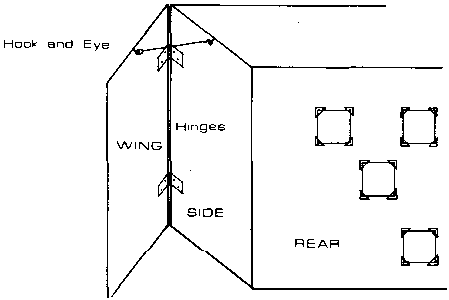

A simple layout such as the one suggested in Figure 1 can be adapted according to your program and resources.

The building materials should be chosen to blend with the surroundings. A building which clashes with the environment does not demonstrate the basic conservation point that people are a part of nature and should work in harmony with it.

Construction information for concrete and bamboo is available in the Village Technology Handbook, or Bamboo as a Building Material (see Chapter Sources).

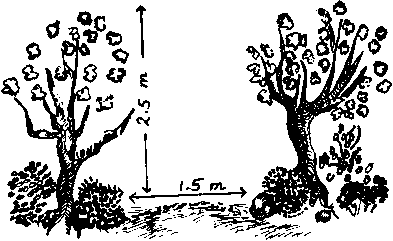

The landscaping of the conservation education center (see Appendix C, Landscaping) should be a careful effort to develop methods and plant materials which visitors can adapt for their own uses. In a region of few plant materials, landscaping may mean that you will work with rocks and gravel to achieve an attractive visual effect. Pots or cans of flowering plants or vegetables may be an effective substitute for ground plantings.

Where there are abundant local plant materials, make a selection based on foliage shapes and textures, leaf and flower colors, height or density. Variety and contrast are important elements in any setting.

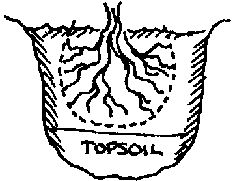

The quality of the soil you have to work with is important to your success in landscaping. The soil can need improvement for its texture or for its fertility. Generally speaking, you can tell yourself if it is too sandy, if it is all clay, or if it lacks topsoil. An addition of decomposed organic matter (which you can make in a compost pile) will benefit the soil quality. To check on the fertility of the soil, it is advisable to have a soil sample analyzed by a government agricultural agency, to see what minerals are lacking, and which fertilizers can be added to correct the lack.

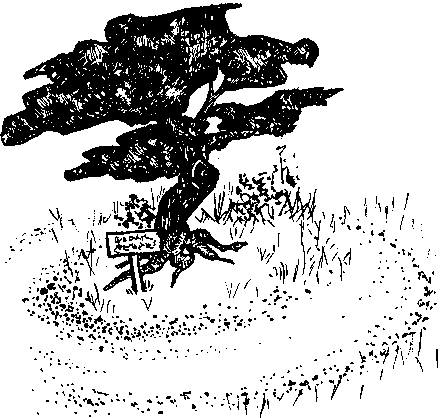

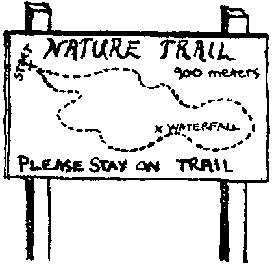

The Nature Trail (See Appendix B. Nature Trails) of the conservation education center provides the most effective tool for teaching environmental relationships. Through direct contact with the natural setting, and with the help of carefully planned interpretive labels and guides, the visitor will be able to understand the living process which can be seen, touched and heard along the trail.

When there is enough space and the habitat is suitable, trails which specialize in the interpretation of one aspect of the environment (geology, wildlife, plant life) can be planned as side loops off the main trail. Other possible ideas for trails are discussed in Appendix B.

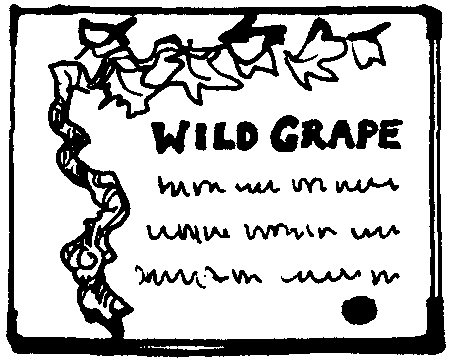

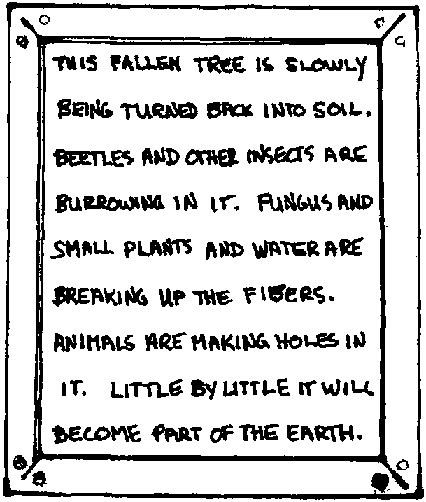

Remember that the signs which you provide for the nature trail are to give guidance and direction, and the labels are to do the interpretive work. Each label should be planned so as to stress the relationship of the interpreted feature with another aspect of the environment. (See Appendix D, Signs & Labels).

An alternative to the system of labeling trailside features is to provide a printed guide. Features along the trail are identified with a number; the corresponding number in the guide tells about this feature. Sample trail guides are provided in Appendix B and Appendix D.

A conservation education center is an ideal place to demonstrate techniques to improve environmental conditions in your region. If space and technical personnel are available, an area where visitors can see how to plant and improve crops, make compost piles, store crops, cultivate fish, etc., can be of great benefit. Peace Corps Manuals for a number of possible projects are listed in the Chapter Sources.

The planning and layout of such an area should be incorporated in the initial conservation education center planning, to assure the best land use both initially and for future development. Consult with regional technical specialists to identify special conservation problems of the area which would benefit from a demonstration project of this sort. Be flexible, innovative and responsive to cooperative efforts, because benefits to people from the total environment is the goal of any conservation program.

You can take advantage of an outdoor area to provide a number of outdoor exhibits which can be entirely separate from the nature trail. Exhibits of this sort will provide additional variety and interest to your conservation education program.

You may want to consider:

- A pool for fish, turtles, frogs or waterplants if there is a small stream which could be dammed;

- a medicinal plant garden featuring local herbs which are medicinally useful;

- a bird bath;

- a soil profile made by exposing the side of a bank, or digging a pit, to show the various layers of soil;

- a rock collection of large rocks labelled as to their type, or simply grouped for their color or shape;

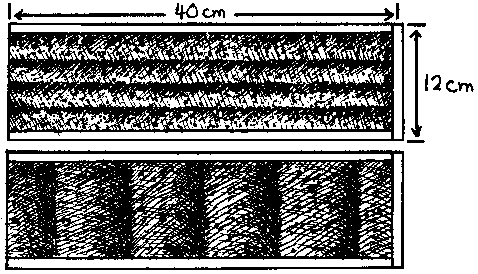

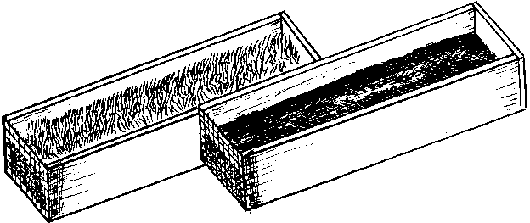

- a tree-ring exhibit with two pieces of a large tree trunk:

1. a sectional slice, sanded and waterproofed with varnish or an oil sealer, can be labeled to tell about the growth rings. Each ring represents a year - the outer ring is the most recent. Dry years have narrower rings than wet ones. Please note that in tropical regions, rings are not an accurate measurement of age.

2. A split section lengthwise of the tree trunk, treated in the same way, can be placed next to the slice to show how the grain of the wood is caused by the yearly growth rings.

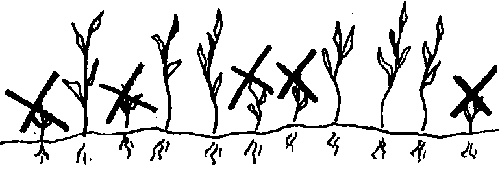

- A grass demonstration in which a plot of ground is seeded to show various grasses for erosion control.

(See Appendix A, Exhibits & Study Materials)

The purpose of the exhibits in a conservation education center is to explain, describe and interpret the natural world outside the center. No exhibit or series of exhibits has to be permanent. Just as the natural world is constantly changing, the exhibits which explain this world should change. This means that expensive and elaborate permanent exhibits are not needed. What is important is the appropriateness of the exhibit to the local conditions and the clarity with which each condition is explained.

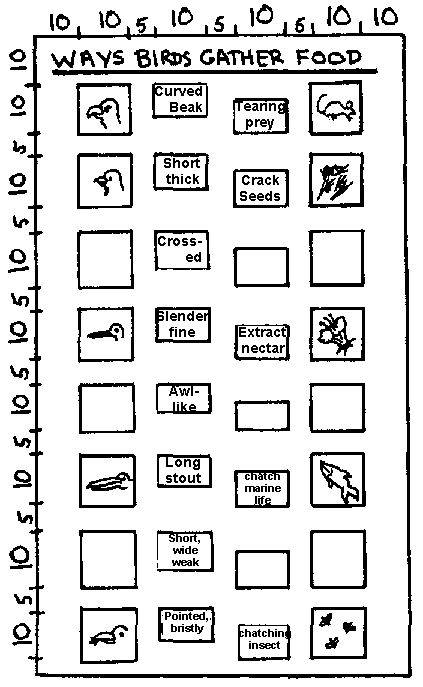

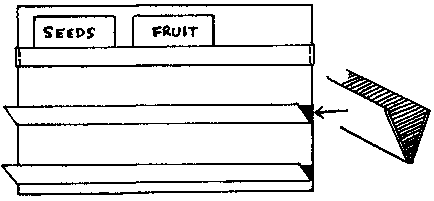

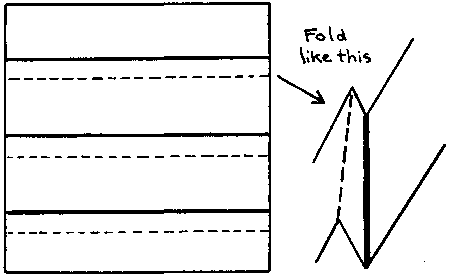

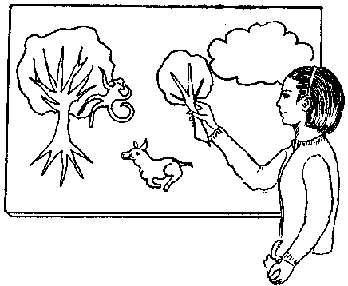

Charts, posters, maps, collections, specimens, small animal exhibits and visitor participation exhibits can all be done in a simple, clear fashion and organized so that each one reinforces the relationships you are trying to demonstrate.

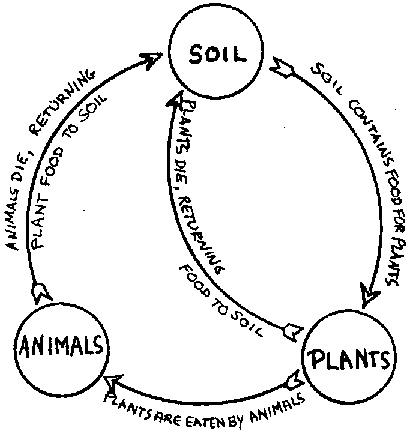

A method of changing exhibits which you might consider is that of providing progressively more detailed information as your visitors become more informed about exhibit subjects. For example, the initial food cycle concept to begin with in conservation education is that of the "food chain" (see Appendix A). As your visitors' understanding of this concept grows, you can present new exhibit material which will demonstrate that the food chain is actually a "food web" that there are generally several consumers at each stage of the cycle, and that there is a "web" of inter-relationships among the eater and the eaten.

Here are some suggested themes around which to organize your exhibits:

- a food chain

- the role of predators

- relation of plants and animals to their environment

- life in a pond

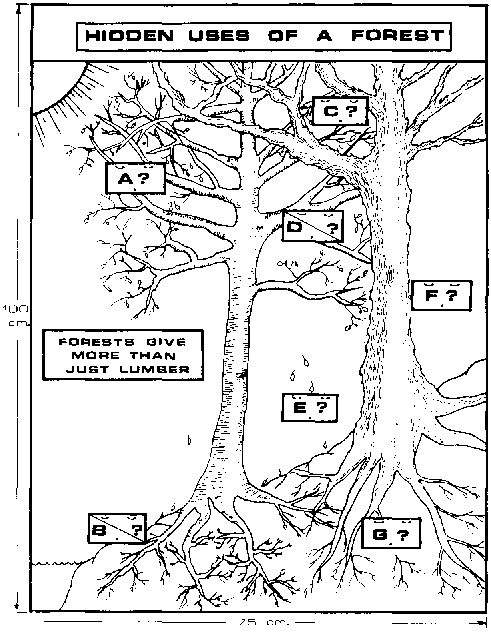

- life in a forest

- life in the desert

- importance of wetlands

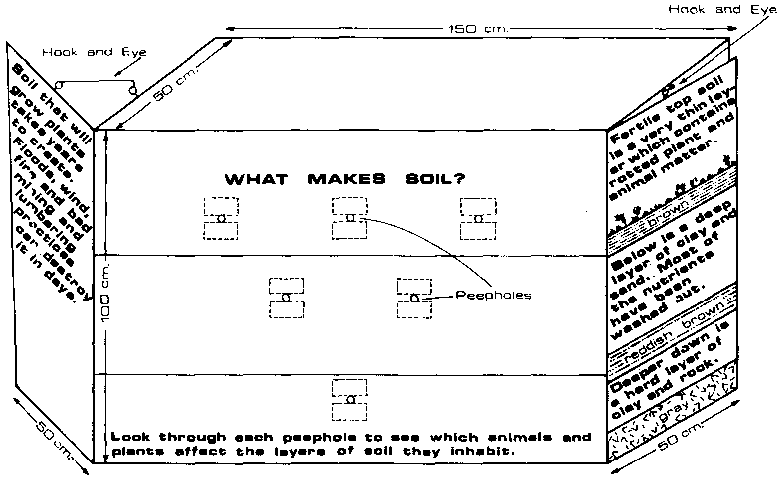

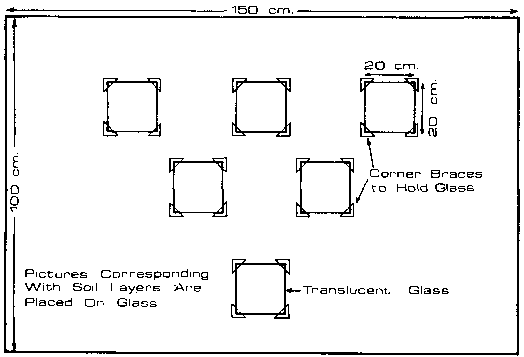

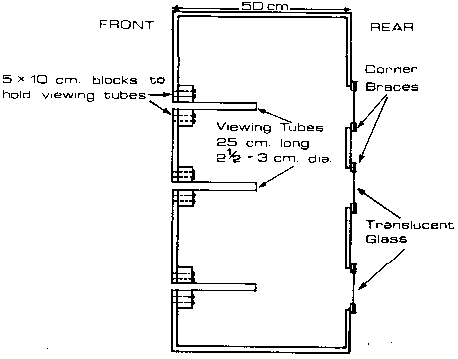

- the make-up of soil

- important rocks and minerals

- geological history

- wind and water erosion

- how a plant grows

- seeds and seedlings

- parasitism (both plant and animal)

- water and air pollution

To provide guidance as you plan the center's exhibits, you will find suggestions for using some of these themes in exhibits, collections and study materials, in Appendix A. As you survey the situation in your own region, you will know what suggestions can be used, which need to be adapted, and which are not applicable.

It is essential that your conservation education program be directly related to the visitor's environment. Broad general themes or problems which exist in another part of the world are not part of the step-by-step development of a basic understanding which you are trying to achieve.

In Appendix F you will find suggestions for various ways to keep live animals that you might exhibit in your conservation education center. Although live animals can provide a good deal of variety and interest to your exhibits, remember that even the smallest insects need attentive care for effective presentation. You must have clean, well-fed and healthy specimens for visitor viewing, otherwise your conservation message is defeated.

Signs at the conservation education center (see Appendix D, Signs, Labels and Guides) will inform the visitor as to places, directions, distances, facilities and regulations. Interpretive needs are usually filled by labels, but a larger sign might identify an unusual tree or other unique feature.

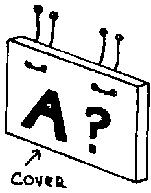

The labels for your exhibits should do two things: (1) identify the object and (2) give the visitors information and an explanation about the object. Identification of an object is short and simple, but how much information and explanation you provide about an object should depend on the visitors' needs. You may feel that some labels should give a good deal of information. In that case, be sure that other labels give just a little information. You do not want to tire visitors by giving them more information than they can absorb. Their experience in the conservation education center should be not only educational, but pleasant.

A conservation education center which is given space in an already existing park (or other governmental) building will be basically an exhibits center. It may be possible, however, if park land is available, to develop some outdoor exhibits, or even a nature trail (Appendix B). Since the indoor exhibits should reflect what is seen outdoors, it would be ideal if the planning for both could be done at the same time. However, if there is resistance to using any land for conservation education purposes, plan your exhibit space to interpret the environmental conditions which are plainly visible outdoors for all to see.

Your exhibits could explain erosion problems, the status of area wildlife, water pollution, the area's plant life, etc. As your center develops and gains acceptance, it may be possible to proceed with a program of labelling interesting and related features found in the park land.

EXHIBITS

The space which you are provided for a conservation education center will determine the extent of your exhibits. Do not crowd your space by trying to demonstrate more ideas than there is room for. It is much better to announce changing exhibits and to feature only a few exhibits at a time. Since exhibits which feature living plants, insects or other animals may not last too long, they make excellent short-term exhibits. (For further discussion of exhibits, and Appendix A and F).

COOPERATION

If you are sharing space with a government agency which is itself involved in conservation, such as wildlife management, forest management, agriculture, fisheries, etc., you have a wonderful source of exhibit ideas, exhibit materials, and possibly of exhibits themselves. Try to develop joint programs in which you might interpret the work the agency is doing, for exhibit in the center. You may be able to develop a speakers' program to provide experts to discuss a specific problem or idea with a school or community group.

LANDSCAPING

If the building in which the conservation education center is located has no landscaping, you may be able, in cooperation with the building director, to develop a plan to demonstrate landscaping ideas. This might be an extensive long range planting of trees, shrubs and ground cover, or it might be only a seasonal placement of containers of flowering plants. (See Appendix C, Landscaping.) Remember that an improvement in our visual environment is one of the benefits of conservation.

SIGNS AND LABELS

In order to encourage visitors to come to the conservation education center which shares a building, you will want to put a sign directing visitors at the entrance to the building.

(For further discussion of signs, and for labelling, and Appendix D, Signs, Labels and Guides.)

Adobe construction methods

California Extension Service Manual 19

University of California

Agricultural Experiment Station & Extension Service

Berkeley, California, USA

Bamboo as a building material

Department of Housing & Urban Development

Office of International Affairs

Washington. D.C. 20410, USA

Building construction in warm climates, vol. 1

R.L. Fullerton

Oxford University Press

Ely House

London W. 1, England

Building with adobe and stabilized earth blocks

Leaflet No. 535

Agricultural Research Service

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Hyattsville, Md. 20782, USA

Excreta disposal for rural areas and small communities1

World Health Organization

Geneva, Switzerland

*Freshwater fish Pond culture and management2

** Peace Corps/VITA

Program & Training Journal

Manual series number 1B

VITA

3706 Rhode Island Avenue

Mt. Rainier, Md. 20822, USA

Handbook for building homes of earth

Department of Housing & Urban Development

Office of International Affairs

Washington, D.C. 20410, USA

Low cost windmills for developing nations

VITA publication 20E

3706 Rhode Island Avenue

Mt. Rainier, Md. 20822, USA

Manual of outdoor conservation education

Nature Center Planning Division

National Audubon Society

950 3rd Avenue

New York, New York, 10022, USA

Manual of outdoor interpretation

Nature Centers Division

National Audubon Society

950 3rd Avenue

New York, New York, 10022, USA

Para que criar abejas

(also available in English)

Vecinos mundiales

Volumen 5 - numero 4S

5116 North Portland Avenue

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73112, USA

Planning a nature center

Nature Center Planning Division

National Audubon Society

950 3rd Avenue

New York, New York 10022, USA

*Reforestation in arid lands2

** Peace Corps/VITA

Program & Training Journal

Manual series number 5

VITA

3706 Rhode Island Avenue

Mt. Rainier, Maryland 20822, USA

*Small farm grain storage2

** Peace Corps/VITA

Program & Training Journal

Manual series number 2

VITA

3706 Rhode island Avenue

Mt. Rainier, Maryland 20822, USA

Trail planning & layout

Nature Center Planning Division

National Audubon Society

950 3rd Avenue

New York, New York., 10022 USA

Why raise bees

(also available in Spanish)

World Neighbors

Volume 5 - number 4E

5116 North Portland Avenue

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73112, USA

Wood preservation

Forest Products Laboratory

Forest Service

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Washington, D. C. 20250, USA

*Village technology handbook

VITA

3706 Rhode island Avenue

Mt. Rainier, Maryland 20822, USA

1

WHO publications available from:Q Corporation

49 Sheridan Avenue

Albany, New York 12210, USA

2

Multiple copies available from:National Technical Information Service

5285 Port Royal Road

Springfield, Virginia 22161, USA

*Available to Peace Corps Volunteers from:

Peace Corps Information Collection & Exchange

Room M-1214

806 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20525, USA

**Single copies available to individuals and non-profit organizations working in the Third World from the above address

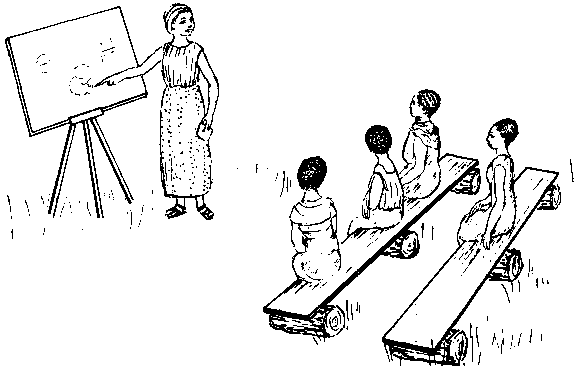

Since the basic function of a conservation education center is to educate people about the close relationships among all living and non-living things in our ecosystem, a school is a natural center for this function.

Depending on the size and level of the school, a program of more or less detailed environmental and conservation education can be developed from materials in this section and in Appendix A, C & F. and from sources listed in the Chapter Sources.

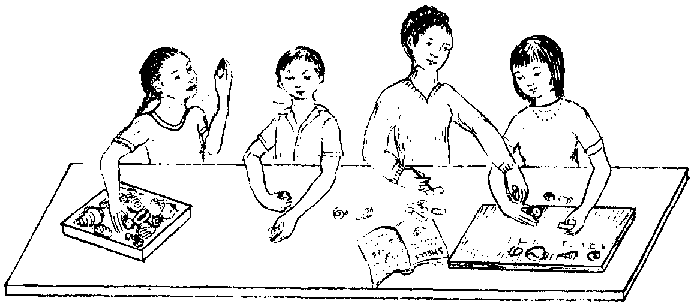

As the students develop their understanding, they carry conservation concepts to the rest of the community, and the experiments they perform, the information they gather, the collections they make can become a community resource as a Conservation Science Fair.

Because the students are beginning to learn and understand conservation concepts at an early age, they will, as they grow older, be ready to accept more complex aspects of these concepts. The more completely a person understands the concepts, the better use he/she can make of his/ her resources.

The teacher who wishes to introduce environmental and conservation studies to his students does not have to be an ecologist, or even a science teacher. The teacher needs only guidance, a willingness to think about what he/she sees in the environment, and enthusiasm to discover how these things are related.

A school program of conservation education can be developed, starting with simple goals of observation and awareness in the first year Studies in each subsequent year will build more detailed understanding of what has gone before.

An outline for a school conservation program is included here.

Objectives

- To develop an awareness of the immediate natural environment; plants, animals, rocks, air, water and soil found at school or in the community;

- To develop an awareness of change in the natural world: how sizes, shapes, colors, sounds, smells, textures, and animal activities vary with the seasons;

- To understand some of the interrelationships among soil, plants, animals, people, water, and air;

- To learn how people depend on soil, water, plants, animals, people, water, and air;

- To learn how people can make their environment cleaner, more healthful, and more beautiful.

Things to Talk About

- What plants and animals are found at school, in the neighborhood, or in the community? Include weeds, rats, domestic animals, fish, birds, insects, earthworms, and ants. How do they affect people? How do people affect them? Begin to learn about classifying by grouping similar things.

- How do the changes in seasons affect plants in the area? Animals? Soil? Water? People? What are some of the different sounds you hear on your way to school? In the town? In the fields?

- What kinds of rocks and soils are found in your neighborhood? How do people use soil? How do plants and animals depend on soil? Do plants grow better in some soils than in others? How is the soil affected by plants, animals, and people?

- In what ways do plants and animals in your community depend on one another? What plants and animals do you depend on for food, shelter, and clothing? How do plants and animals depend on you?

- In what ways do plants, animals, and people depend on sunshine and rain? For what purposes do we use water at school? At home? In the town? On a farm? How are water and air affected by plants, animals, people, and soil? What happens to rain when it falls on the soil? On roads?

- Do we need to take care of soil, water, plants, animals and air? Why? What are some things you can do to make your community cleaner, more healthful, and more beautiful?

Things to Do

- Take a walk around the school site and neighborhood, or to a vacant lot or nearby park and make a list of things observed. Afterwards draw pictures or tell stories about some of the things seen on the walk.

- Collect samples of soil from three different locations and examine them for differences in color and texture.

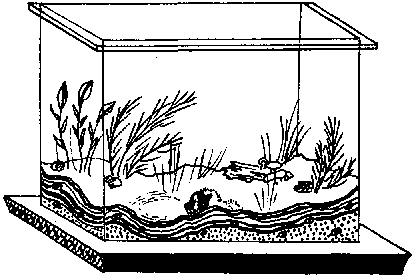

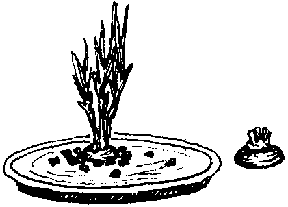

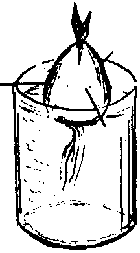

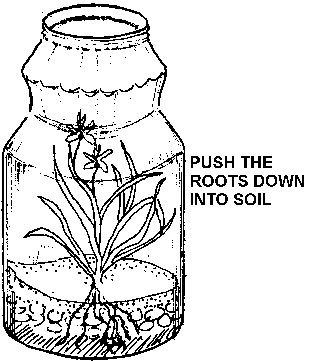

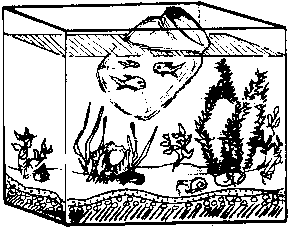

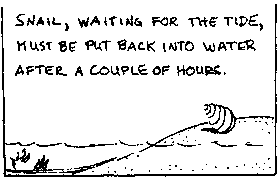

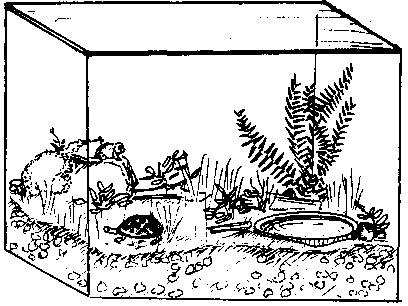

- Build a balanced aquarium or terrarium to learn how plants and animals depend on each other, Make a windowsill garden to learn how plants grow and how to take care of them.

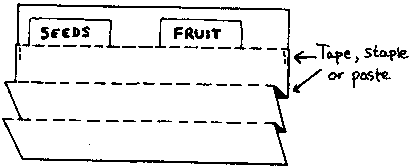

- Collect seeds or leaves for a classroom display; compare their sizes, shapes and textures. Show in the display how seeds might travel from one location to another.

- Take a walk in the rain to observe how rain strikes the soil, road, grass and trees; how soil moves with surface water; how raindrops cling to leaves; and how leaves slow the force of raindrops and help protect the soil.

- Plan and carry out cleanup and planting projects on the school site or in the community.

(See Appendix A, C & F for further suggestions and information)

Objectives

- To increase awareness of change, variety, similarities, and interrelationships within the natural environment

- To develop an awareness of people as a part of the natural world and their role in changing the environment.

- To learn how rocks are continually being changed into soil; how soils differ; how soil is moved; and how soil can be conserved.

- To understand how the life of a plant or animal is affected by its environment.

- To understand how animals depend directly or indirectly on food from green plants for energy and growth.

- To learn more about how people depend on each other and on soil, water, plants. animals and air.

Things to Talk About

- What kinds of food and clothing do we get from wildlife, domesticated animals, and plants?

- How do animals such as mammals, birds, fish and insects help people?

- What objects do you use everyday? Classify them as coming from animals, plants, or minerals.

- Discuss how your everyday activities affect natural resources. How do you make use of soil, trees, shrubs, flowers. water, domesticated animals, and wildlife?

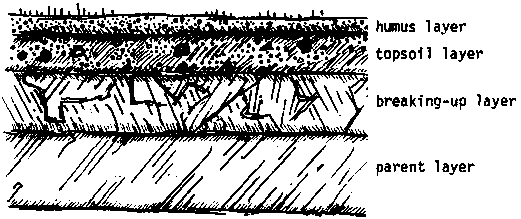

- How is soil made? What are the effects of wind, water, and plants on rocks? Do animals live in the soil? Are air and water found in the soil?

- Discuss the differences and similarities in sand, clay, and silt. How do they compare with soil from a good garden? What makes plants grow better in good garden soil?

- What natural forces move soil? Why should we conserve soil? How do plants help hold the soil in place?

- Name places where soil is washing away in your area, and discuss some ways to prevent soil washing away.

- How does the appearance of trees, flowers, water, insects, birds, wildlife, and domesticated animals change with the seasons?

- How do wild animals store food? How do people store food?

- Compare plants and animals living in your community with those in the ocean, in a pond, in a desert and in a forest. How are they similar? How are they different?

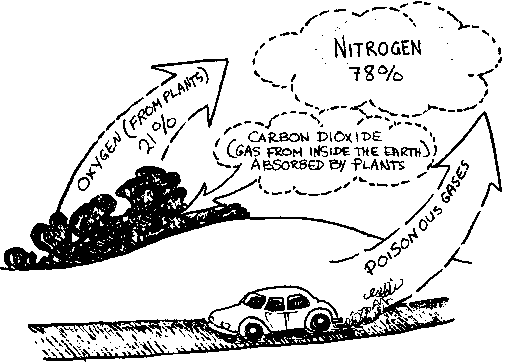

- How do green plants make their own food from water, air, sunlight and minerals from the soil? Can animals and people make their own food from these raw materials? Trace some foods eaten by animals and people to green plants and the soil.

- How do people who live in cities and towns depend on farmers? How do farmers depend on people in cities and towns? Discuss some kinds of work done by people as they make use of natural resources to produce food, shelter, and clothing.

Things to Do

- Keep a weekly record during the school year of changes in a tree, a vacant lot, or an area of the school yard.

- Collect different kinds of leaves. What do they have in common? How are they different? Match the leaves with the trees they come from, and sketch the shape of different trees. What happens to the leaves left on-the ground?

- Make some "soil" by rubbing soft stones or bricks together. Compare this material with soil from the school yard and discuss what changes take place as the rock particles become soil.

- Demonstrate that soil contains water, air and living organisms.

- Find an area near the school where water or wind has moved the soil. Develop a project showing how to keep the soil in place.

- Take a walk on a windy day to observe how wind moves clouds, leaves, seeds and soil. Show how grass and shrubs keep soil from blowing.

- Show how plants depend on soil, water, air, and light.

- Make murals and sketches to show how items you use every day come from the soil.

- Visit someone in your community that uses natural resources in processing or making products.

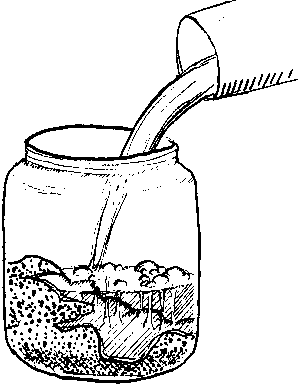

- Measure the amount of sediment in a jar of water taken from a stream immediately after a rainstorm, and measure the amount of sediment in water taken from the same stream a week after the rainstorm. Allow the water to stand at least 24 hours before measuring and comparing the amounts of sediment found in each jar.

- List ways people protect their natural resources and ways people use them carelessly.

(See Appendix A, C & F for further suggestions and information).

Objectives

- To understand how one natural environment differs from another natural environment.

- To learn how living things adapt to different environments.

- To understand how available natural resources influence the way people live.

- To understand how people change the environment as they Use natural resources.

- To learn about different conservation practices and to understand the need for them in taking care of natural resources.

Things to Talk About

- What is an environment? What are some of the natural factors that limit plant and animal life in your community?

- How is your environment different from the environment in which a bird lives? a fish? a cactus?

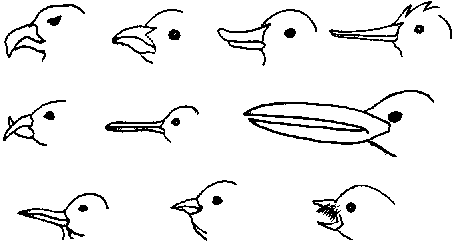

- Name some of the physical characteristics of plants and animals that enable them to adapt to different environments. How have people learned to adapt to different environments? Why can some animals live in several different environments?

- Why are most towns and cities located along rivers or near lakes? Where does your community get its water supply?

- In what ways are farmland, grazing land, forests, wildlife and minerals important to your community?

- Discuss the different purposes for which soil is used in the city and in rural areas.

- In what forms have you seen water? What causes water to change form, and how do the different forms affect human activities?

- How are plants, animals, soil and water affected when people use large areas of land for houses or roads, or urban development?

- Where does soil go when water washes it off unprotected areas?

- What is sediment? How does sediment in rivers and lakes affect fish and wildlife? The water you use every day?

- What are some conservation practices used by farmers or others in your community to prevent soil from washing into rivers and lakes?

Things to Do

- Select a plant or an animal found on the school site; explain what it needs for survival and how the environment meets its needs.

- Visit a nearby park, wooded area, or pond. List the plants and animals that are the same as, and those that are different from, the ones found on the school grounds. Explain the physical characteristics of the plants and animals that enable them to live where they do. Examine the soils in each place. Describe how different soils affect the plants and animals living in each area.

- Build a balanced aquarium or terrarium and then change one element at a time to determine the effect on the environment.

- Draw the main characteristics of forest, grassland, and desert environments; describe how they differ from each other.

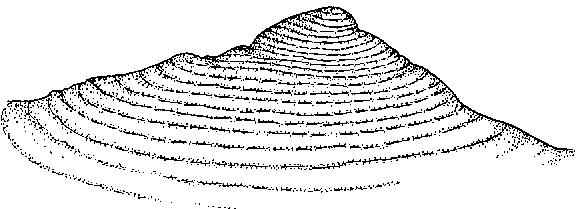

- Study a soil profile in a road cut or excavation site. Identify the surface soil, subsoil, and parent material. Describe the differences in color and texture of the three layers. (See page 118)

- Conduct an experiment to find out if soil particles are all the same size.

- Compare the water running off a bare slope with water flowing from a grass-covered slope during a gentle rain. Collect a jar of water from both areas and compare the amount of sediment in each.

- Visit a farm where conservation practices are used.

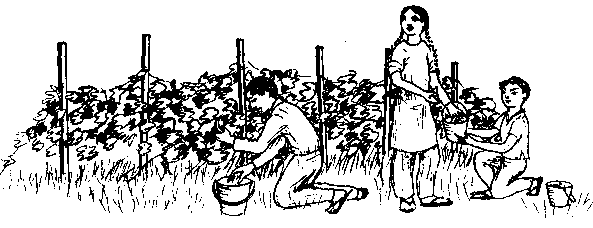

- Start a school garden with different kinds of plants. Learn how to manage soil and water resources to encourage the growth of these plants.

- Keep a daily weather chart for a month. Draw pictures of the cloud formations most likely to produce rain.

- List the products made from natural resources in your community and how and where they are used.

- Make a study of the school grounds and plan a conservation project to improve the environment for plants, animals, and people.

(See Appendix A, C & F for further suggestions and information).

Objectives

- To understand the inorganic and organic cycles within the natural environment.

- To learn more about the ways resources are changed through use.

- To understand the water cycle and how people in different environments manage water resources.

- To understand some of the relationships among natural resources within a watershed, and how the protection and management of watersheds affect the quality of the environment.

- To learn how conservation practices can help people improve their environment, and to understand some of the choices they must make in applying such practices.

Things to Talk About

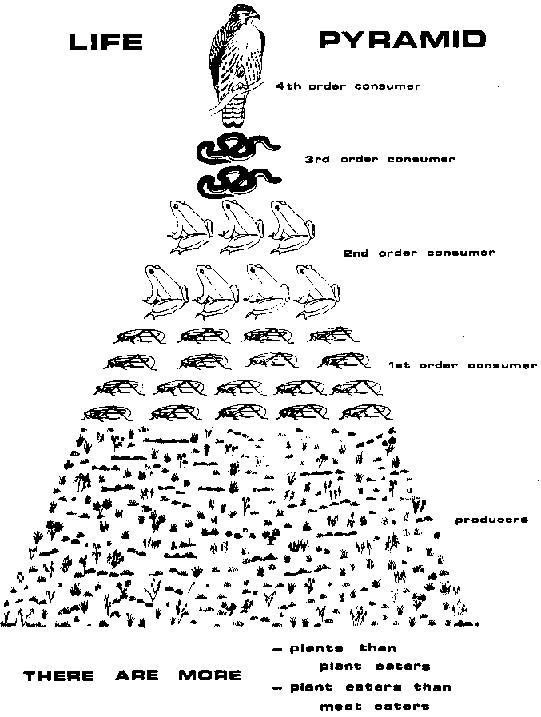

- What is a food chain? A food pyramid? Why does it take 1000 kilos of plant plankton to produce 10 kilos of commercial fish that can produce a weight gain of 1 kilo in a person?

- How are producers, consumers, and decomposers related?

- Is soil a renewable natural resource? How does soil develop? How do decomposers help return organic matter to the soil? Name some materials that do not decompose readily. Explain some methods people might use to recycle these materials.

- What are the sources of oxygen on earth? In how many ways do people use oxygen?

- What is a watershed? Does the way the land is used in the watershed affect water in small streams? In rivers?

- What happens to water when it falls on the road? Rooftops? Soil? 'What determines how much water runs off and how much soaks into the soil? How do the different kinds and amounts of plant cover help water soak into the soil?

- What happens to water once it enters the soil? Why is ground water important to plants and to people?

- How does the amount of soil that washes off unprotected land into streams, rivers and lakes affect your water supply?

- Trace the history of natural resource use in your watershed and community. What plants and animals were once found there? What new plants and animals have been introduced?

- What things should be considered when deciding how the water resources in your watershed are managed? What choices must be made? What different kinds of conservation practices might be used? Which ones are needed in your community?

Things to Do

- Show in a diagram, beginning with the soil, several food pyramids having at least three levels. Draw a food chain with people in it.

- Study the plants and animals on and near the school site, in the outdoor classroom, in a vacant lot, in a nearby field, in the woods or in a pond. How do the plants and animals differ in one area from those in another? How are they similar? How have people changed these areas? Discuss how plants or animals have adapted to the environment in these areas.

- Write or tell stories about some of the ways people have either improved or harmed the environment for living things, or how your environment has changed because of people's influence.

- Make a mural of the water cycle and show what happens to rain when it falls to earth.

- Visit a cutover or burned-over forest, or a building site, where topsoil is being washed away. Determine how the sediment-filled water drains to a stream and what effect it may have on your water supply and on the people and towns farther downstream.

- Where does your water come from? Can you visit the source? Is the water filtered, chemically treated or boiled before it is used?

- Draw a map of your watershed showing where conservation practices are needed and where they have been applied.

- Show the different rates at which water soaks into three different kinds of soil.

- Demonstrate how slopes and hills affect the way water runs off the land. Show some of the ways the water can be slowed down as it runs off a slope. Show how a hard rain splashes soil.

(See Appendix A, C & F for further suggestions and information).

Objectives

- To become aware of the way decisions about use of resources and energy by people affect the natural environment.

- To understand how the environment influences our way of life and the kind of work we do.

- To understand some of the effects of natural and man-made changes in the environment.

- To understand how natural resources contribute to the industrial development of a nation.

- To understand how social and economic factors influence use and management of soil, water, air, plants, animals, and minerals.

- To learn how people plan and take action to conserve natural resources.

Things to Talk About

- How are living things changed as their environment changes? What are some examples of living things that could not adapt to their changing environment? In what ways did people bring about these changes?

- How do people use science and technology in adapting to the environment? Have scientific (including medical) discoveries changed your environment? How?

- What role has the environment played in influencing the way of life for a tribe of nomads? a fishing village? a farming community? your community?

- How do droughts, floods, fire, soil erosion, water and air pollution, the construction of roads and cities affect plants? animals? people?

- What is the relation of population growth to the quality of your environment?

- What is the effect on people, animals, and plants when natural resources are abused, exhausted, or improved? What happens to the economy? to society?

- Name as many sources of energy as you can.

- How is the price of grain affected by factors in the environment?

- What should people know about resource potentials and problems in their area? What are some of the laws that affect use and management of natural resources in your community? Why are these laws necessary?

- How can you help improve your environment?

Things to do

- Interview older people in your community to learn about changes in the local environment during their lifetime. Include such things as changes in number of people, land use changes, scientific and technological discoveries, and changes in transportation systems. What effect has each of these changes had on soil, water, animals and people?

- Locate an area in which natural resources have deteriorated. Form small student groups to prepare reports detailing conservation needs. Outline a plan of action for improving the area.

- Select a resource problem area on the school site or nearby, and carry out a project, including application of a specific conservation practice, to improve the area.

- Make a chart of the natural resources of your country, and what they are used for.

(See Appendix A, C & F for further suggestions and information).

Objectives

- To understand our responsibilities for use and management of our environment.

- To develop additional understandings of natural resources needed to apply conservation practices.

- To learn how the natural environment serves as inspiration for creative art: painting, music, storytelling, and poetry, and how natural resources contribute to the production of materials used in painting, sculpture, and other art forms

- To learn what your community is doing to the environment.

- To learn what government agencies are doing to help protect and conserve natural resources.

- To understand the need to use ecological principles as guides for conservation action.

Things to Talk About

- What characteristics do people share with other living things? How does our ability to plan and achieve objectives make us different from other living creatures?

- What changes caused by people's use of resources have had or continue to have a detrimental effect on your environment? What changes have a beneficial effect?

- What are people's responsibilities to other living things as we make use of resources?

- How do resources contribute to the social and economic development of your country? of the world?

- Do the decisions on resource use in your community affect your country? What conservation practices can be used in your community to improve the resources needed by your country?

- How might natural resources serve as themes in painting, music, dance, writing or other creative work? What natural resources are used in the creation of art? What art materials are made from natural resources?

- What are the conservation and environmental problems of your community? What treatments are needed? Why?

- What kinds of sewage and solid waste disposal are used in your community? What effects do these methods have on underground water supplies? on public health? on environmental quality? Do these methods contribute to water or air pollution?

Things to Do

- Locate an eroding area on the school site or nearby, and determine the probable cause or causes of the erosion. Design and carry out a plan to control the erosion and to prevent similar problems in the future.

- List how the family of each student in your class makes use of natural resources.

- Make a map of your community to show the boundaries of several watersheds, and to show how these watersheds form the drainage basin of a river.

- Visit artists in your community to learn how they use natural resources as inspiration for their works.

- Think of songs which show how music can interpret the environment. Write a song that describes some aspect of the natural environment.

- Compile a list of government agencies with conservation and resources management responsibilities. Contact a conservation office in government or a university to find out what conservation measures they are taking which might affect your community. Can you help in any way?

- Visit a state park, forest, wildlife refuge, or farm; report on the resource management objectives and procedures used to achieve them.

- Make a conservation inventory of your community. Determine alternative solutions for several of the problems observed. Make sketches when collecting information.

- Develop an outdoor classroom for your school. Select an area with many different learning opportunities. Inventory the existing vegetation, boulders, streams, and special areas that could be used for learning. What kinds of information on soil and water conservation are needed? Make a guidebook for younger classes to use,

- Design a conservation oriented science fair. Develop projects and estimate the time needed to prepare them so that all projects will be ready for the fair.

- Construct a simple, functioning habitat containing at least three different plants and two different animals. Make and record observations daily for a month.

(See Appendix A, C & F for further suggestions and information).

Adapted with permission from the U.S. Soil Conservation Service publication "An Outline for Teaching Conservation in Elementary Schools".

A science fair is a gathering together for public display of a school's scientific studies, presented on charts, graphs, posters, in exhibits, experiments and collections, for the purpose of communicating information. When the theme of the fair is Conservation, then those informational charts and graphs, experiments and collections all deal with the many aspects of conservation which the students have investigated. Since there are many ways conservation techniques can improve community life, a conservation science fair can be a valuable opportunity to demonstrate ideas which can be adapted for individual application.

You will find subjects for display at a conservation science fair in the outline for school study beginning in Appendix A, Exhibits and Study Materials; in Appendix C, Landscaping; and in Appendix C, Live Animals. See also Chapter Sources.

The subjects that you chose as projects for a conservation science fair should be those which are most directly related to the local conditions This will make the fair more interesting and understandable to its visitors.

Before beginning a project for the fair, you should know what you want to demonstrate; then plan the project for that purpose. When the project is ready for display, be sure it is carefully and effectively labelled to give all the information you want to communicate.

Conservation science fair projects

Soil Conservation Society of America

7515 N. E. Ankeny Road

Ankeny, Iowa 50021, USA

L'Enseignement de la nutrition à l'école1

(also available in English and Spanish)

Etudes de nutrition de la FAO #25

Food & Agricultural Organization of the United Nations

available from FAO agents world-wide; or Distribution & Sales Section FAO, Via delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy

Environmental education activities manuals

Environmental Education Program

School of Natural Resources

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104, USA

Environmental education, an annoted bibliography of selected materials and services

Smithsonian institution - Peace Corps Environmental Program

Washington, D.C. 20560, USA

*Glossary of environmental terms. Spanish-English, English-Spanish2

** Peace Corps information Collection & Exchange

Program & Training Journal, Reprint series #17

Room M-1214

806 Connecticut Avenue N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20525, USA

*Manual didactico: Huertos escolares y nutricion2

** Peace Corps information Collection & Exchange

Program & Training Journal, Reprint series #18

Room M-1214

806 Connecticut Avenue N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20525, USA

Nosotros y la naturaleza: Guia para professores, Guia para estudiantes

Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje

Division Agropecuaria

Region de Neiva

Colombia

Outline for teaching conservation in elementary schools (PA-268)

Soil Conservation Service

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Washington, D.C, 20250, USA

People and their environment (8 guides)

Teachers Curriculum Guide to Conservation Education

J.G. Furguson Publishing Co.

6 N. Michigan Avenue

Chicago, Illinois 60602, USA

Soil & water conservation in Barbados

4-H Division Extension Services

Ministry of Agriculture

Barbados

Teacher's guide to minigardens

Science Study Aid #2

Agricultural Research Service

U.S. Department of Hyattsville,

Maryland, 20782, USA

The teaching of rural science in tropical primary schools1

UNESCO publication

Paris 7, France

Teaching soil & conservation: A classroom & field guide (PA-341)

Soil Conservation Service

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Washington, D.C. 20250, USA

Forest Service

Environmental Education Office

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Washington, D.C. 20250 USA

(materials related to environmental education)

Martin County Schools

Environmental Studies Center

2900 N.E. Indian River Drive

Jensen Beach, Florida 33457

(primary school manuals for ocean-related environmental studies)

National Audubon Society

950 3rd Avenue

New York, New York, 10022, USA

(many kinds of environmental materials available)

National Wildlife Federation

1412 16th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036 USA

(many kinds of environmental materials available including "Ranger Rick's Nature Magazine", "Environmental Discovery Units")

Soil Conservation Service

Education information Office

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Washington, D.C. 20240 USA

(materials related to conservation, including "Soil Conservation" monthly magazine)

1

English editions of UN and FAO publications available from:UNIPUB

P.O. Box 433

Murray Hills Station

New York, New York 10016, USA

2

Multiple copies available from: National Technical informationService

5285 Port Royal Road

Springfield, Virginia 22161, USA

*Available to Peace Corps Volunteers from:

Peace Corps information Collection & Exchange

Room M-1214

806 Connecticut Avenue N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20525, USA

**Single copies available to individuals and non-profit organizations working in the Third World from the above address

All living things, together with all non-living things, form our ecosystem. People are a part of the ecosystem; people are a natural resource; since conservation is concerned with the care of natural resources, people must take care of themselves as well as the rest of their environment. Health care is conservation too'

In many parts of the world the major problems of health are malnutrition and diseases carried by insects and parasites. These are environmental problems.

An environment in which there is improper or insufficient food is usually the result of poor agricultural production, poor soil, poor food storage methods, and lack of knowledge about nutrition. An environment which supports a disease-carrying insect cycle, such as the mosquito/malaria cycle, or the tsetse fly/sleeping sickness cycle, is a bad environment for people. An environment which supports the unchecked growth of bacteria is a bad one for people.

People can change the environment to improve the soil, agricultural production and nutrition, to break the cycle of disease carriers, or slow the growth and spread of bacteria, if they understand the problem and learn what steps to take.

A health center provides medical care for its community. It should also provide health education. Just as conservation education shows the relationship between all things in an environment, health education can show the relationship between health problems and the local environment.

To establish a health conservation education program in your community health center, you will need to identify those health problems which are most directly related to your own environment, and which are caused by such things as poor sanitation, erosion or crop destruction, or insect carriers. Choose one of these problems at a time, if your center is small, as a demonstration and education project.

The results of malnutrition on a nation's development cannot be ignored. When a large portion of the population is unable to realize its potential due to improper physical development or disease caused by poor diet, the loss to the nation is great. The periods of infancy and childhood require sizeable resources from both the family and the nation in terms of food and health care. When a child dies in adolescence, his/her use of those resources is totally lost. If he/she does not have a reasonably long or useful working life, again the food and health care used in his development will not be fully repaid, and the nation is losing a valuable natural resource.

The World Health Organization believes that protein calorie deficiency is the greatest public health problem in the world today. A health center conservation project that could be developed in cooperation with an agricultural agency would demonstrate how to develop better soil, how to choose an acceptable protein-rich plant food to grow, and how to prepare it for eating. (Protein-rich soybeans might be a possible crop to introduce). You will need a piece of land for a demonstration garden (see Appendix C for growing information and Chapter 5 for agricultural information).

If other kinds of diet deficiencies are an important problem in your area, a demonstration garden could grow those plant foods which would eliminate the deficiencies. You would have to work with the agricultural agent to identify which plants would grow well, and would also be culturally acceptable to these garden demonstrations. If the climate is suitable, papaya trees could be introduced to provide an easily grown source of vitamins A and C.

Another possibility might be the introduction of fish culture through a program following the Peace Corps/VITA manual, Freshwater Fish Pond Culture and Management Fish are an important protein-rich food and to grow fish in ponds is a more certain way of supplying fish for food than trying to catch fish from lakes, rivers or streams.

Nutrition education can be supported through the schools where children can learn the basic principles of good nutrition. They could grow fresh vegetables or fruits in a school demonstration garden, which they could take home to eat. A government-sponsored food program might be available to provide school children with a nutritionally balanced meal each day.

If floods or erosion are a frequent cause of crop loss in your area, you should encourage efforts in flood and erosion control by farmers, with help from agricultural agents, which would improve the local food supply. (See Chapter 5).

Where food supplies are threatened by loss during preservation and storage, improvement such as that detailed in the Peace Corps/VITA manual, Small Farm Grain Storage (see Chapter Sources), should be actively encouraged and supported by cooperative efforts with agricultural agents. Proper storage can reduce grain loss from 33% to 3% thus making an increased quantity of food available.

In urban areas, nutritional problems are intensified by the fact that consumer goods compete for whatever money is earned, and often the family diet loses out in this competition. An approach to this problem could be to illustrate, by using a flannelgraph story in the health center, that the balanced nutritious diet improves weight, muscular strength, endurance, and capacity to work as well as resistance to disease All of these qualities would tend to increase a person's ability to compete successfully in his/her environment.

Perhaps you could locate some land within the urban area which could be transformed into a community garden for supplementary food needs.

The health center should actively promote food cultivation as a health conservation measure. The health center must be the leader in suggesting and developing ideas to improve the community's nutrition. For an excellent book on the subject, see Learning Better Nutrition by Jean Ritchie/FAO (See Chapter Sources).

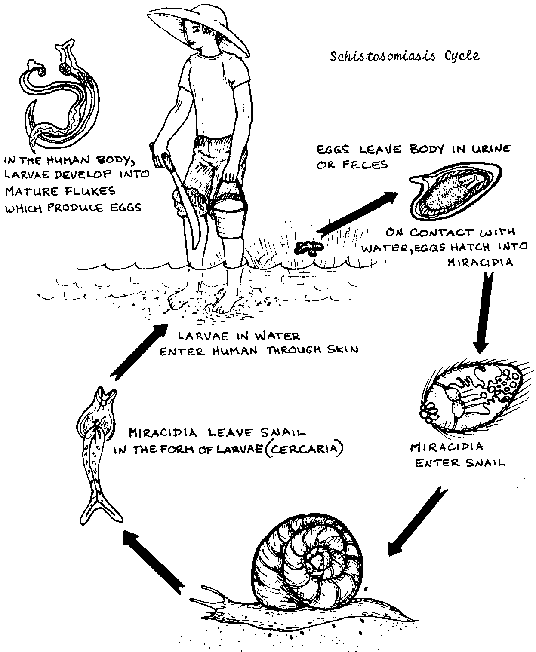

Sanitation is the planning and application of measures to maintain a healthy environment. These measures should apply to water supply, sewage and garbage disposal, and control of disease-carrying insects and animals.

WATER SUPPLY

A community's water supply may come from a ground water well, a spring, a stream, a river or a lake. Unless there is a community-wide water purification system, whatever water there is should be considered to be a potential source of infection and parasites, because human or animal feces or urine, or other untreated sewage, often infect the supply. Therefore, water should be disinfected by each user. The most effective method of preventing water-carried infection and parasites is to boil the water hard for at least ten minutes. This kills bacteria and parasite eggs in the water.

Water purification can be done on a community-wide basis by adding chlorine or iodine to a water storage area. These methods are discussed in the Village Technology Handbook by VITA (See Chapter Sources).

A health center should be concerned with educating a community to develop a clean water source. This would involve educating people to (1) build and use latrines, not the river or lake; (2) put their garbage in compost piles not in or near the water supply; (3) not bathe in the water supply; (4) keep domestic animals out of the water supply; (5) Use erosion control techniques to keep topsoil from washing into the water supply. Other local sources of water contamination should be studied and remedied.

SEWAGE

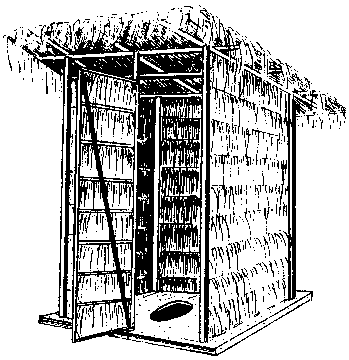

Sewage is the term used for human wastes. Sewage can be properly disposed of by use of latrines. Latrines can be built for each family, or one or several can be built for the community as a whole. A family is likely to keep its latrine clean, and is likely to use it; too often no one feels personal responsibility for keeping the community latrine clean or in good repair. Where possible, you should encourage people to build family rather than community latrines.

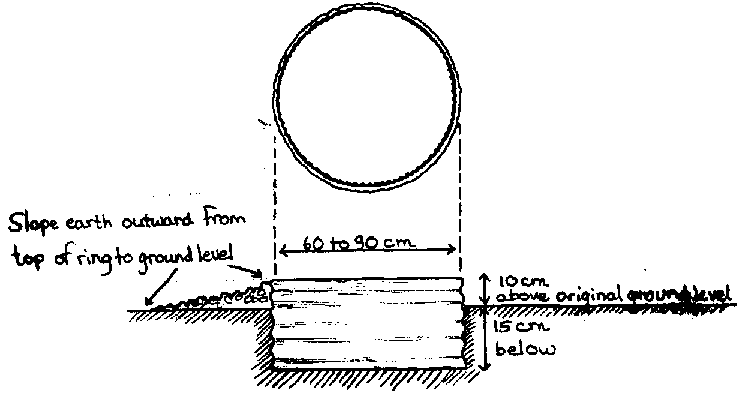

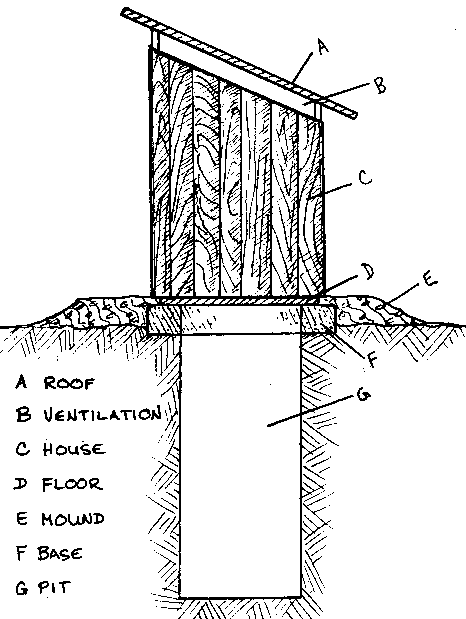

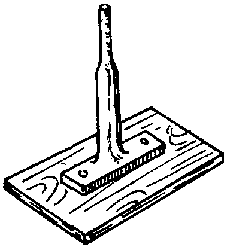

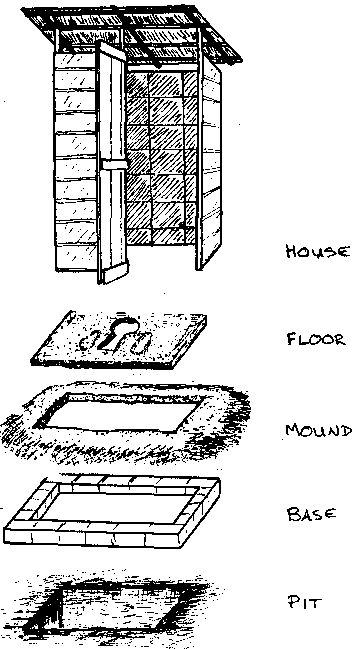

Pit Latrines

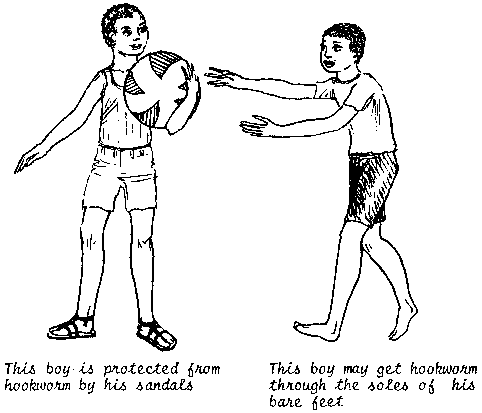

A pit latrine is basically a hand-dug hole in the ground, covered with a slab, preferably of concrete, either for squatting or with a seat. A shelter is built around it. Human wastes are isolated and stored in the pit latrine, so that no harmful bacteria or parasites can be passed on from the wastes to new hosts. In the pit, the wastes decompose, first into odorous ammonia products, then into nitrites and nitrates. This decomposition process generally kills the majority of harmful organisms. An exception is the hookworm's eggs which remain alive for up to five months in wet. sandy soil.

Hookworm larvae can climb up pit walls and survive on a cracked wooden or earth floor, and once there, they can be picked up by bare feet. It is highly recommended that a concrete slab provide the cover for the pit and that it be effectively and frequently flushed with water. Flies are common carriers of disease organisms found in feces. They crawl and feed on this material, which sticks to the flies' bodies, and which later to the flies' bodies, and which later may be deposited on human food, either directly or through the fly's feces. For this reason, it is important to try to discourage flies in a latrine. The best way to do this is to plan a well-ventilated, dark shelter, since flies do not like darkness, Use fine-mesh screening to cover openings if it is available. A 10% surface layer (2.5 cm) of borax has been found to discourage flies. Use of insecticides has been found to develop a fly population resistant to insecticide control. A cover for the nit opening in strongly suggested.

A health center should provide help and information about latrine building. The most complete source of information and directions is Excreta Disposal for Rural and Small Communities, published by WHO, portions of which appear in Village Technology Handbook by VITA.

You should build a pit latrine at an easy distance from the home so as not to discourage its use. It should be down-hill from any ground water supply, in a dry, well-drained area, above flood level. Around the latrine, clear an area 2 m wide of all vegetation and debris, to discourage shelter for animals and insects. This may be done gradually, to gain acceptance of a latrine in a spot where the surrounding vegetation was formerly used.

Since each geographical area will have certain taboos about the collection and disposal of human waste, you will have to identify these before developing an acceptable solution. Privacy and the separation of the sexes may be important considerations. (Also see Appendix E).

GARBAGE

Garbage is basically food waste, but can also include other unwanted materials such as paper, cans, bottles. The more a community consumes, the more garbage to be disposed of.

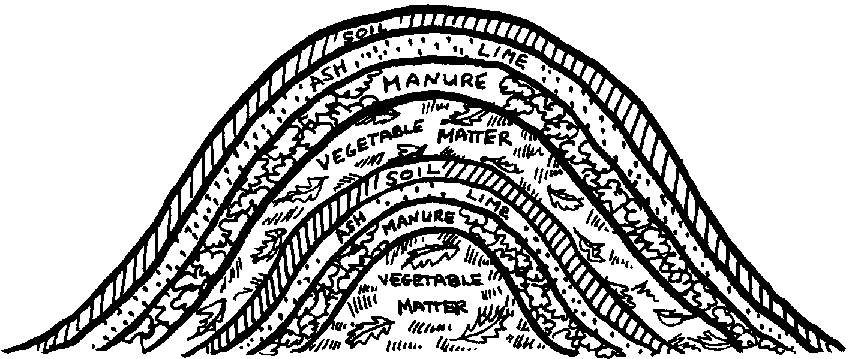

From a conservation standpoint, food wastes should be returned to the soil as a compost material. This adds both nutrients and organic materials to the soil which will increase its fertility. See Appendix C, for information on making a compost pile. A compost pile can be a family or a community project. If there is space available outside a health center, a demonstration compost pile can be built with organic wastes from the community members. When the compost is ready for garden use, it can form the basis for a demonstration garden, or can be divided among the community members for their own garden use.

Non-organic wastes such as metals or glass should be disposed of in a single community site, a large pit for example, to keep the community clean and free from litter. If possible, the disposal area should be visually separated from the community, either by distance or by a screen of plants.