Original editon 1981

Second printing 1984

Report of an Ad Hoc Panel of the

Advisory Committee on Technology Innovation

Board on Science and Technology for International Development

Commission on International Relations

National Research Council

HUGH POPENOE, Director, International Programs in Agriculture, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA, Chairman

STEVE P. BENNETT, Bennett's Animal Clinic, Port of Spain, Trinidad, West Indies

CHARAN CHANTALAKHANA, Dean, Department of Animal Science, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand

DONALD D. CHARLES, Senior Lecturer, Meat Production, Department of Animal Husbandry, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Queensland, Australia

W. ROSS COCKRILL, Livestock Expert, Food and Agriculture Organization (retired), Rome, Italy

WYLAND CRIPE, Department of Veterinary Science, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA

TONY J. CUNHA, Dean, School of Agriculture, California Polytechnic University, Pomona, California, USA

A. JOHN DE BOER, Winrock International Livestock Research and Training Center, Morrilton, Arkansas, USA

MAARTEN DROST, Department of Veterinary Science, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA

MOHAMED ALI EL-ASHRY, Department of Animal Production, Faculty of Agriculture, Shoubra el Khiema, Cairo, Egypt

ABELARDO FERRERD ., Former Director, Breeding Administration Centers, Animal Sciences Division, Ministry of Agriculture, Caracas, Venezuela

JEAN K. GARDNER, Former Chief, Logistics Division USAID/Philippines, Jackson, Mississippi, USA

JAMES F. HENTGES, Department of Animal Science,University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA

JACK HOWARTH, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, California, USA

NELS M. KONNERUP, Livestock Expert, Agency for International Development (retired), Washington, D.C., USA

A. P LEONARDS, Water buffalo breeder, Lake Charles, Louisiana, USA

JOHN K. LOOSLI, Department of Animal Science, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA

JOSEPH MADAMBA, Director, Asian Institute of Aquaculture, Iloilo, Philippines

CRISTO NASCIMENTO,Director, Brazilian Agriculture Research Corporation (EMBRAPA), Agriculture Research Center for Humid Tropics (CPATU), Belem, Para, Brazil

DONALD L. PLUCKNETT, Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, The World Bank, Washington, D.C., USA

WILLIAM R. PRITCHARD, Dean, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, California, USA

J. THOMAS REID, (deceased), Department of Animal Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA

JOHN H. SCHOTTLER, Animal Production Officer, Department of Primary Industries, Lae, Papua New Guinea

DALBIR SINGH DEV, Dean, Animal Science Department, College of Agriculture, Agricultural University, Ludhiana, Punjab, India

ROBERT W. TOUCHBERRY, Dean, Department of Animal Science, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA

DONALD G. TULLOCH, Division of Wildlife Research, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Winnellie, Australia

NOEL D. VIETMEYER, Board on Science and Technology for International Development, National Research Council, Washington, D.C., Staff Study Director

MARY JANE ENGQUIST, Board on Science and Technology for International Development, National Research Council, Washington, D.C., Staff Associate

The water buffalo is an animal resource whose potential seems to have been barely recognized or examined outside of Asia. Throughout the world there are proponents and enthusiasts for the various breeds of cattle; the water buffalo, however, is not a cow and it has been neglected. Nevertheless, this symbol of Asian life and endurance has performed notably well in recent trials in such diverse places as the United States, Australia, Papua New Guinea, Trinidad, Costa Rica, Venezuela, and Brazil. In Italy and Egypt as well as Bulgaria and other Balkan states the water buffalo has been an important part of animal husbandry for centuries. In each of these places certain herds of water buffalo appear to have equaled or surpassed the local cattle in growth, environmental tolerance, health, and the production of meat and calves.

Although these are empirical observations lacking painstaking, detailed experimentation, they do seem to indicate that the water buffalo could become an important resource in tropical, subtropical, and warm temperate zones in developing and developed countries.

If this is the case, then it is clear that many countries should begin water buffalo research. Serious attention by scientists could help dispel the misperceptions and uncertainties surrounding the animal and encourage its true qualities to emerge.

This report describes the water buffalo's attributes as perceived by several animal scientists. It is designed to present the apparent strengths of buffaloes compared with those of cattle, to introduce researchers and administrators to the animal's potential, and to identify priorities for buffalo research and testing.

The panel that produced this report met at Gainesville, Florida, in July 1979. It was composed of leading water buffalo experts (particularly those from outside Asia who have directed the beginnings of water buffalo industries in their countries) and leading American animal scientists, many of whom are also familiar with the animal.

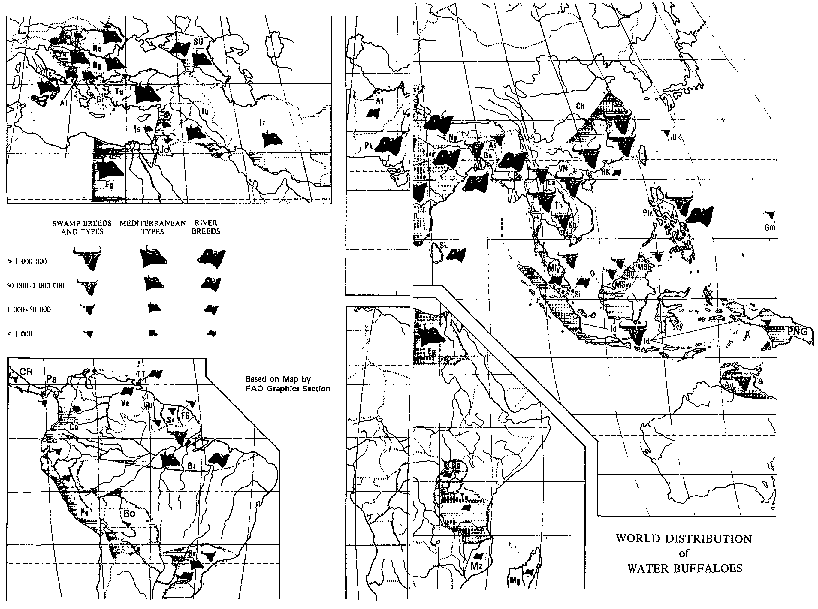

This report complements The Husbandry and Health of the Domestic Buffalo, edited by W. Ross Cockrill and published in 1974 by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Cockrill's 933-page book is a "bible" of water buffalo knowledge and provides details of breeds, world distribution, physiology, and an extensive bibliography.

The present report is an introduction to the water buffalo and its potential. It is written particularly for decision makers, as well as scholars or students, in the hope that it will stimulate their interest in the animal and thereby increase the appreciation of, and funding for, buffalo research. The report includes much empirical observation, largely from the panel members. Some of these observations may, in the long run, prove not to be universally applicable. Much benchmark information needs to be obtained.

Since its creation in 1971, the Advisory Committee on Technology Innovation (ACTI) has investigated innovative ways to use current technology and resources to help developing countries. Often this has meant taking a fresh look at some neglected and unappreciated plant or animal species. The committee assembles ad hoc panels of experts (usually incorporating both skeptics and proponents) to scrutinize the topics selected. The panel reports serve to draw attention to neglected, but promising, technologies and resources. (For a list of ACTI reports, see page 115.) ACTI reports are provided free to developing countries under funding by the Agency for International Development (AID).

Program costs for this study were provided by AID'S Office of Agriculture, Development Support Bureau, and staff support was provided by the Office of Science and Technology, Development Support Bureau.

The final draft of this report was edited and prepared for publication by F. R. Ruskin. Bibliographic editing was by Wendy D. White. Cover art was by Deborah Hanson.

The domesticated water buffalo Bubalus bubalis numbers at least 130 million-one-ninth the number of cattle in the world. It is estimated that between 1961 and 1981 the world's buffalo population increased by 11 percent, keeping pace with the percentage increase in the cattle population.

Although there are some pedigreed water buffaloes, most are nondescript animals that have not been selected or bred for productivity. There are two general types-the Swamp buffalo and the River buffalo.

Swamp buffaloes are slate gray, droopy necked, and ox-like, with massive backswept horns that make them favorite subjects for postcards and wooden statuettes in the Far East. They are found from the Philippines to as far west as India. They wallow in any water or mud puddle they can find or make. Primarily employed as a work animal, the Swamp buffalo is also used for meat but almost never for milk production.

River buffaloes are found farther west, from India to Egypt and Europe. Usually black or dark gray, with tightly coiled or drooping straight horns, they prefer to wallow in clean water. River buffaloes produce much more milk than Swamp buffaloes. They are the dairy type of water buffalo. In India, River buffaloes play an important role in the rural economy as suppliers of milk and draft power. River buffaloes make up about 35 percent of India's milk animals (other than goats) but produce almost 70 percent of its milk. Buffalo butterfat is the major source of cooking oil (ghee) in some Asian countries, including India and Pakistan.

Although water buffaloes are bovine creatures that somewhat resemble cattle, they are genetically further removed from cattle than are the North American bison (improperly called buffalo) whose massive forequarters, shaggy mane, and small hindquarters are unlike those of cattle. While bison can be bred with cattle to produce hybrids,( This is not, however, very successful, the male progeny (at least of the F 1 generation) are sterile).there is no well-documented case of a mating between water buffalo and cattle that has produced progeny.

Parts of Asia and even Europe have depended on water buffaloes for centuries. Their crescent horns, coarse skin, wide muzzles, and low-carried heads are represented on seals struck 5,000 years ago in the Indus Valley, suggesting that the animal had already been domesticated in the area that is now India and Pakistan. Although buffaloes were in use in China 4,000 years ago, they are not mentioned in the literature or seen in the art of the ancient Egyptians, Romans, or Greeks, to whom they were apparently unknown. It was not until about 600 A.D. that Arabs brought the animal from Mesopotamia and began moving it westward into the Near East (modern Syria, Israel, and Turkey). Water buffaloes were later introduced to Europe by pilgrims and crusaders returning from the Holy Land in the Middle Ages. In Italy buffaloes adapted to the area of the Pontine Marshes southeast of Rome and the area south of Naples. They also became established in Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, Greece, and Bulgaria and have remained there ever since.

Villagers in medieval Egypt adopted the water buffalo, which has since become the most important domestic animal in modern Egypt. Indeed, during the last 50 years, their buffalo population has doubled to over 2 million head. The animals now supply Egypt with more meat-much of it in the form of tender "veal"-than any other domestic animal. They also provide milk, cooking oil, and cheese.

Other areas have capitalized on the water buffalo's promise only in very recent times. For instance, small lots of the animals brought to Brazil (from Italy, India, and elsewhere) during the last 84 years have reproduced so well that they now total about 400,000 head and are still increasing, especially in the lower Amazon region. Buffalo meat and milk are now sold widely in Amazon towns and villages; the meat sells for the same price as beef. Nearby countries have also become familiar with the water buffalo. Trinidad imported several breeds from India between 1905 and 1908, while Venezuela, Colombia, and Guyana have been importing them in recent decades. During the 1970s Costa Rica, Ecuador, Cayenne, Panama, Suriname, and Guyana introduced small herds. By 1979 the buffalo in Venezuela numbered more than 7,000 head.

Across the Pacific, the new nation of Papua New Guinea has found the water buffalo well suited to its difficult environment. For 9 years the government has attempted to run cattle on the Sepik and Ramu Plains on Papua New Guinea's north coast, where the temperatures are high and the forage of poor quality. But the cattle remain thin and underweight. In the 1960s animal scientists began evaluating water buffaloes already living in Papua New Guinea and, encouraged by the results, introduced additional buffaloes from Australia. These have performed remarkably well, producing greater numbers of calves and much more meat than the cattle in the region. The buffaloes appear to maintain appetite despite the heat and humidity, whereas cattle do not. The government of Papua New Guinea has since imported more water buffaloes and today has thriving herds totaling almost 3,500 head.

The United States has been slow to recognize the water buffalo's potential, but the first herd (50 head) ever imported for commercial farming arrived in February 1978.(Air-freighted from the wilds of Guam, the U.S. island possession on the western Pacific, by panel member Tony Leonards. Prior to that time (in 1974), four head of water buffalo were imported to the Department of Animal science' university of Florida, for study. The only other water buffaloes in North America were a few animals in zoos.) The humble water buffalo, normally considered fit only for the steamy rice fields of Asia, is now proving itself on farm fields in Florida and Louisiana. As a result, interest in the animal is on the rise in U.S. university and farm circles.

From experience accumulated in Asia, Egypt, South America, Papua New Guinea, Australia, the United States, and elsewhere, animal scientists now perceive that many general impressions about the water buffalo are incorrect.

For example, it is widely believed that the water buffalo is mean and vicious. Encyclopedias reinforce this perception, and in the Western world it is the prevalent impression of the animal. The truth is, however, that unless wounded or severely stressed, the domesticated water buffalo is one of the gentlest of all farm animals. Despite an intimidating appearance, it is more like a household pet-sociable, gentle, and serene. In rural Asia the care of water buffaloes is often fumed over to small boys and girls aged about four to nine. The children spend their days with their family's gentle buffalo, riding it to water, washing it down, waiting while it rolls and wallows, and then riding it to some source of forage, perhaps a grassy field or thicket. It is not uncommon to see a buffalo patiently feeding, with a young friend stretched prone on its broad gray back, asleep.

Perhaps the notion about the viciousness of water buffaloes stems from confusing them with the mean-tempered African buffalo Syncerus caffer, actually a distant relative with which they will not interbreed and which is classified in a different genus.

Ferocity is the most blatant misconception concerning the water buffalo, although other fallacies are widely reported as well.

One generally held belief is that water buffaloes can be raised only near water. Actually, buffaloes love to wallow, but they grow and reproduce normally without it, although in hot climates they must have shade available.

Another belief is that the water buffalo is exclusively a tropical animal. River-type buffaloes, however, have been used to pull snow plows during Bulgarian winters. They are found in Italy (over 100,000 head), Albania, Yugoslavia, Greece, Turkey, the Georgia and Azerbaijan areas of the Soviet Union (almost 500,000 head) and other temperate-zone regions as well. They are also found in cold, mountainous areas of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Nepal.

Yet another misconception is that the water buffalo is just a poor man's beast of burden. In addition to providing fine lean meat, buffaloes in fact provide rich milk. Mozzarella cheese, one of the most popular in Europe, comes from the buffaloes in Italy. Buffalo milk has a higher content of both butterfat and nonfat solids than cow's milk does. It therefore often brings higher prices than cow's milk. Throughout much of India it is in such demand that cow's milk is sometimes hard to sell.

Many of the misconceptions generally held about buffaloes are based on little data and much prejudice. For instance, it is widely believed that water buffalo meat is tough and less desirable than beef. However, when the animals are raised for meat, buffalo steaks are lean, as tender as beef, and in appearance it is difficult to distinguish the two. In taste-preference tests at the University of Queensland, buffalo steaks were preferred over those from Angus and Hereford cattle. Tests conducted in Trinidad, Venezuela, the United States, and Malaysia produced similar results.

Australia has shipped water buffalo meat to Hong Kong, the United States, Germany, and Scandinavia. Buffalo meat is now available in stores in Australia's Northern Territory, where demand exceeds supply. It sells at competitive prices and is particularly sought for barbecues and the famous Australian meat pie. In the Philippines, two-thirds of the meat consumed in homes and restaurants is actually water buffalo, a fact that many Filipinos do not realize.

Compared with cattle,waterbuffaloes apparently have an efficient digestive system, one which extracts nourishment from forage so coarse and poor that cattle do not thrive on it. Thin cattle are commonly seen in Asia and northern Australia, for example, but it's rare to see a protruding rib on a buffalo, even though it uses the same source of feed.

In Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, water buffaloes live on coarse vegetation on the marginal land traditionally left to the peasants. They help make human survival possible. An old Chinese woman in Taiwan once told panelist W. Ross Cockrill: "To my family the buffalo is more important than I am. When I die, they'll weep for me; but if our buffalo dies, they may starve."

A better understanding of the water buffalo could be invaluable to many developing nations. In particular, improved production of water buffalo meat offers hope for helping feed India, the second most populous nation on earth. Although India for religious reasons forbids the slaughter of cows, it has no prohibitions regarding slaughter of water buffaloes or the consumption of buffalo meat.

Most developing countries are in the tropics, and the water buffalo is inherently a tropical animal. It is comfortable in hot, humid environments. In the Amazon, for example, buffaloes are now common on the landscape and may even replace cattle completely.

Tropical countries have more serious disease problems than temperate countries do. Although susceptible to most cattle diseases, the water buffalo seems to resist ticks and often appears to be more resistant to some of the most devastating plagues that make cattle raising risky, difficult, and sometimes impossible in the tropics. Several researchers report that when water buffaloes are allowed to wallow, their mud-coated skin seems to deter insect and tick ectoparasites and they consequently require greatly reduced treatment with insecticides. Although the buffalo fly (Siphona exigua) affects the animals, other pests such as the warble fly and the screwworm, for example, seldom affect healthy buffaloes. AIso, despite their inclination for living in swamps, Avers, and ponds, diseases of the feet such as foot rot and foot abscesses are rare.

Another benefit to developing countries is the water buffalo's legendary strength. A large part of the total farm power available in South China, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, the Indochina states, India, and Pakistan comes from this "living tractor." Dependable and docile, the animals pull plows, harrows, and carts with loads that weigh several tons. In the Amazon buffalo teams pull boats laden with cargo and tourists through shallows and swamps.

The petroleum crisis has forced many farmers to reconsider animal power even in some of the technically advanced countries. Buffaloes are not only extraordinarily strong, they can also work in deep mud that may bog down a tractor. Even up to their bellies they forge on, dragging both plow and driver through the mud. Although its average walking speed is only about 3 kilometers per hour, the buffalo, unlike its mechanical competition, doesn't need gasoline or spare parts and its working life is often 20 years or more.

Breeds

As already noted, the major genetic divisions of the water buffalo are the Swamp buffalo of the eastern half of Asia, which has swept-back horns, and the River buffalo of the western half of Asia, which usually has curled horns. There is also the Mediterranean buffalo, which is of the River type but has been isolated for so long that it has developed some unique characteristics. (Records of the buffalo in Italy date back 1,000 years, during which there have been no reported imports.) Mediterranean buffaloes are stocky, high yielding animals that combine both beef and dairy characteristics.

Although there is only one breed of Swamp buffalo, certain subgroups seem to have specific inherited characteristics. For example, the buffaloes of Thailand are noted for their large size, averaging 450-550 kg, and weights of up to 1,000 kg have been observed. Elsewhere, Swamp buffaloes range from 250 kg for some small animals in China to 300 kg in Burma and 500-600 kg in Laos.

Only in India and Pakistan are there well-defined breeds with standard qualities. There are eighteen River buffalo breeds in South Asia, which are further classified into five major groups designated as the Murrah, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Central Indian, and South Indian breeds. These are the five groups and main breeds:

|

Group |

Breeds |

|

Murrah |

Murrah, Nili/Ravi, Kundi |

|

Gujarat |

Surti, Mehsana, Jafarabadi |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

Bhadawari, Tarai |

|

Central Indian |

Nagpuri, Pandharpun, Manda, Jerangi, Kalahandi, Sambalpur |

|

South Indian |

Toda, South Kanara |

The best-known breeds are Murrah, Nili/Ravl, Jafarabadi, Surti, Mehsana, and Nagpuri. Most of the buffaloes of the Indian subcontinent belong to a nondescript group known as the Desi buffalo. There is no controlled breeding among these animals and most are quite small, yield little milk, and are variable in color.

Genetics

The Swamp buffalo has 48 chromosomes, the River buffalo, 50. The chromosomal material is, however, similar in the two types and they crossbreed to produce fertile hybrid progeny. Cattle, however, have 60 chromosomes and although mating between cattle and buffaloes is common, hybrids from the union are unlikely to occur.( In 1965 a reputed hybrid was born at Askaniya Nova Zoopark in the Soviet Union (see Gray, A., 1971. Mammalian Hybrids, Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, Slough, England, p. 126). Hybrids have also been reported from China (Van Fu-Czao 1959, Gibridy buivolc i krupnogo i rogatogo skota(buffalo and cattlehybrids)Zhivotnovodstro, Mosk., 21:92). Both of these reports seem doubtful because despite many attempts, no other hybrids have ever been claimed to have been produced).

Individual buffaloes show large variation in milk yield, conformation, horn shape, color, meat production, temperament, growth rate, and other characteristics. Selection for survival under adverse conditions has occurred naturally (those that could not stand adversity died early) and farmers have probably tended to select animals of gentle temperament. But systematic genetic improvement has almost never been attempted. It seems likely that further selection could quickly improve their productivity.

Unfortunately, the large bulls that would be best for breeding purposes are often being selected as draft animals and castrated, or sent to slaughter, or (as with some feral animals in northern Australia and on the Amazon island of Marajo) shot by hunters. The result is that the buffalo's overall size in countries such as Thailand and Indonesia has been decreasing as the genes for large size and fast growth are lost.

Limitations

The buffalo is still largely an animal of the village, and many of its reported limitations are caused more by its environment than by the animal itself. Moreover, much of the animal's genetic potential is obscured by environmental influences. For example, for many breeds and types the genetic variations in milk yield and growth cannot be accurately determined because they are overwhelmed by the effects of inadequate nutrition and management.

Nevertheless, some inherent limitations of buffaloes can be identified. For instance, buffaloes suffer if forced to remain, even for a few hours, in direct sunlight. They have only one-tenth the density of sweat glands of cattle and their coating of hair is correspondingly sparse, providing little protection from the sun. Accordingly, buffaloes must not be driven over long distances in the heat of the day. They must be allowed time for watering and, if possible, for wallowing. Driving under a hot sun for long hours will cause heat exhaustion and possibly death; losses can be very high and can occur suddenly. Young calves are particularly affected by heat.

Buffaloes are also sensitive to extreme cold and seem less able than cattle to adapt to truly cold climates(A rule of thumb is that buffaloes don't do well where the sun is inadequate to ripen, say, cotton, grapes, or Ace. Kaleff, B., 1942. Der Hausbuffel und seine Zuchtungsbiologie im Vergleich zum Rind. Zeitschsift Tierzucht Biologze, 51:131-178). Sudden drops in temperature and chill winds may lead to pneumonia and death.

The water buffalo is usually found m areas where there is ready access to a wallow or shower. This is not a necessity, but when temperatures are high the availability of water is important for maintaining buffalo health and productivity. It seems clear, then, that the buffalo is not suitable for arid lands.

Increasing buffalo productivity through breed improvement is just now beginning. Throughout Asia buffalo mating is almost completely haphazard, and so the animal lacks the quality improvement through breeding that most cattle have had. Therefore, most buffaloes are of nondescript heritage and genetic potential.

On poor quality feed water buffalo grow at least as well as cattle, but under intensive conditions they probably won't grow as fast as the best breeds of cattle. In feedlots, therefore, the buffalo is likely to be less productive than improved cattle. Weight gains of about 1 kg per day have been recorded, some exceptional cattle may gain at almost twice that rate.

The buffalo has long been considered a poor breeder-slow to mature sexually, and slow to rebreed after calving. Accumulated experience now shows, however, that this is mainly a result of poor management and nutrition. Buffaloes are not sluggish breeders. Nevertheless, their gestation period is about a month longer than that of cows, buffalo estrus is difficult to detect, and many matings occur~at night so that~ farmers are likely to encounter more problems breeding buffaloes than cattle.

Buffaloes are gentle creatures, but if roughly or inexpertly handled they can, through fear or pain, become completely unmanageable. Buffalo behavior sometimes differs from that of cattle. For example, most buffaloes are not trained to be driven. Instead, the herdsman must walk alongside or ahead of them; they then instinctively follow. Also, because of their innate attachment to an individual site or herd it is more difficult to move buffaloes to new locations or herds. In addition, buffaloes respect fences less than cattle do and when they have the desire to move they are harder to contain. (Electric fences, however, will stop them.)

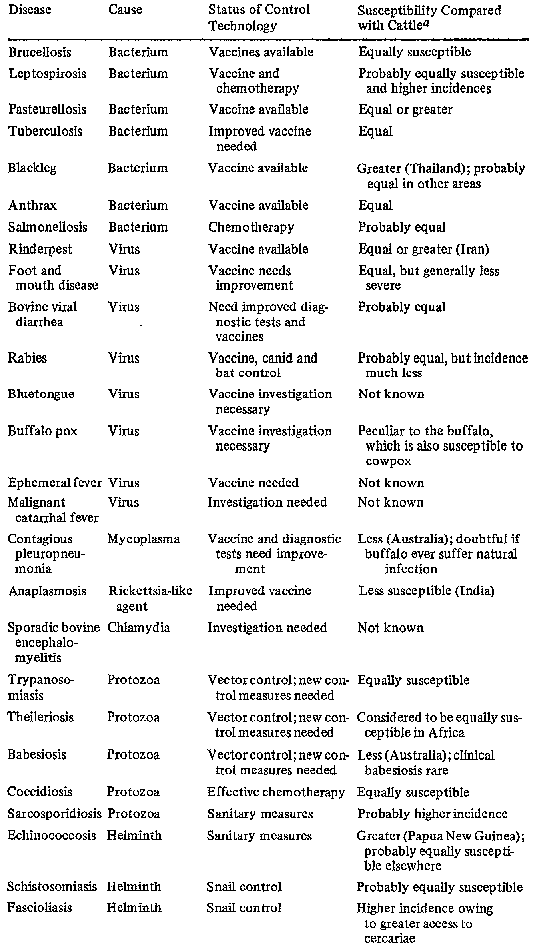

Despite their general good health, buffaloes are probably as susceptible as cattle to most infections. However, the buffalo seems to be peculiarly sensitive to a few cattle diseases and resistant to a few others (see chapter 7). Reactions to some diseases seem to vary with region, environment, and breed, and the differences are not well understood.

Destruction of the environment is sometimes attributed to buffalo wallowing. This danger seems to have been overstated, except in cases where stocking rates were unreasonably high.(An ongoing study in Northern Australia of environmental degradation widely attributed to buffalo has now shown that the effects are caused by man and climatic changes and only very slightly by buffaloes. (information supplied by D. G. Tulloch.) ) However, buffaloes rub against trees more often than cattle do, and they sometimes de-bark the trees, causing them to die.

Unfortunately, some of the best genetic stocks of water buffaloes exist in areas where certain infections and viral and other diseases sometimes occur. Thus, many countries are reluctant to permit importation of water buffaloes, despite the fact that modern quarantine procedures under conditions of maximum security can essentially eliminate the risk.

Finally, it must be emphasized that because buffalo research has been largely neglected, most results reported in this and other buffalo writings cover small numbers of animals and short periods of time. Many are merely empirical observations that have not been subjected to independent confirmation.

Selected Readings

Anonymous. 1972.Buffalo at the crossroads. World Farming 14(n:l0-l3.

Asian and Pacific Council. 1979. Priorities in buffalo research identified.ASPAC News letter No. 43.

Bowman, J. c. 1977. Animals for Man. Edward Arnold Publishers, Ltd., London, United Kingdom.

Buffalo Bulletin. Newsletter published by the Buffalo Research Committee of Kasetsart University, Bangkok' Thailand. (In English and Thai.)

Buffalo World. Newsletter published by the National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, 132001, Haryana, India.

Chantalakhana, C. 1975. The buffaloes of Thailand-their potential, utilization and conservation. In: The Asiatic Water Buffalo. Proceedings of an International Symposium held at Khon Kaen, Thailand, March 31-April 6, 1975. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

Chantalakhana, C., and Na Phuket, S. R. 1979. The role of swamp buffalo in small farm development and the need for breeding improvement in Southeast Asia. Extension Bulletin No. 125. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

Cockrill, W. R. 1967. The water buffalo. Scientific American 217:118.

Cockrill, W. R., ed. 1974. The Husbandry and Health of the Domestic Buffalo. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

Cockrill W. R. 1975. The domestic buffalo. Blue Book for the Veterinary Profession No. 25. Animal Production and Health Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

Cockrill, W. R. 1976. The Buffaloes of China. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

Cockrill, W. R., ed. 1977. The Water Buffalo. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

Cockrill, W. R. 1977. The water buffalo: domestic animal of the future. Bovine Practitioner 12:92-98.

Cockrill, W. R. 1978. Domestic water buffaloes. In: The Care and Management of Farm Animals, edited by W. N. Scott. Bailliere TindaU, London, United Kingdom.

Cockrill, W. R. 1980. The ascendant water buffalo-key domestic animal. World Animal Review 33:2-13.

DeBoer, A. J. 1972. Technical and economic constraints on bovine production in three villages in Thailand. Dissertation Abstracts International 33(5):1935.

DeBoer, A. J. 1975. Livestock and Poultry Industry in Selected Asian Countries. Report of Survey on Diversification of Agriculture: Livestock and Poultry Production. Asian Productivity Organization, Tokyo, Japan.

de Guzman, M. R., Jr. 1979. An overview of recent developments in buffalo research and management in Asia. Extension Bulletin No. 124. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

Documentation Center on Water Buffalo. 1978. Abstract Bibliography on Water Buffalo, 1971-1975. Documentation Center on Water Buffalo, University of the Philippines at Los Banos Library, College, Laguna 3720, Philippines.

Fahimuddin, M. 1975. Domestic Water Buffalo. Oxford and IBH Publishing Company, New Delhi, India

Fischer, H. 1975. The water buffalo and related species as important genetic resources: their conservation, evaluation and utilization. In: The Asiatic Water Buffalo. Proceedings of an International Symposium held at Khon Kaen, Thailand, March 31-April 6 1975. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

Ford, B. D., and Tulloch, D. G. 1977. The Australian buffalo-a collection of papers. Technical Bulletin No.18. Department of the Northern Territory, Animal Industry and Agriculture Branch, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, Australia.

Gupta, H. C. 1977. Possibilities and realities of developing buffalo's performance, breeding and feeding. Indian Dairyman 29(6):337-346.

Kartha, K. P. R.1965. Buffalo. In: An Introduction to Animal Husbandry in the Tropics edited by G. Williamson and W. J. A. Payne. Longman, London, United Kingdom.

McKnight, T. L. 1971. Australia's buffalo dilemma. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 61(4):759-773.

Madamba, J. C., and Eusebio, A. N. 1979. Developments in the strengthening of buffalo research in Asia. Buffalo Bulletin 2(3):7-16.

Mahadevan, P. 1978. Water buffalo research-possible future trends. World Animal Review 25: 2-7.

Oloufa, M. M. 1979. Buffaloes as producers of meat and milk. Egyptian Journal of AnimalProduction 19:1-10.

Pant, H. C., and Roy, A. 1972. The water buffalo and its future. In: Improvement of Livestock Production in Warm Climates, edited by R. E McDowell. W. H. Freeman and Company, San Francisco, California, USA.

Philippine Council for Agriculture and Resources Research. 1978. The Philippines Recommends for Caraboo Production, PCARR, Los Banos, Laguna 3732, Philippines.

Ranjhan, S. K., and Pathak, N. N. 1981. Management and Feeding of Buffaloes. Vikas Publishing House, New Delhi, India

Robinson, D. W. 1977a. Livestock in Indonesia. Research Report No. 1. Centre for Animal Research and Development, Bogor, Indonesia. (In English and Indonesian.)

Robinson, D. W. 1977b. Preliminary Observations on the Productivity of Porking Buffalo in Indonesia. Research Report No. 2. Centre for Animal Research and Development, Bogor, Indonesia. (In English and Indonesian.)

Sundaresan, D. 1979. The role of improved buffaloes in rural development. Indian Dairyman 31(2):73-78.

Tulloch, D. G. 1978. The water buffalo, Bubalus bubalis, in Australia: grouping and home range.Australian Wildlife Research 5:327-34.

Wahid, A. 1973. Pakistani buffaloes. World Animal Review 7:22~28.

The water buffalo offers promise as a major source of meat, and the production of buffaloes solely for meat is now expanding.

Because buffaloes have been used as draft animals for centuries, they have evolved with exceptional muscular development, some weigh 1,000 kg or more. Until recently, however, little thought was given to using them exclusively for meat production. Most buffalo meat was, and still is, derived from old animals slaughtered at the end of their productive life as work or milk animals. As a result, much of the buffalo meat sold is of poor quality. But when buffaloes are properly reared and fed, their meat is tender and palatable.

Water buffaloes are exported for slaughter from India and Pakistan to the Middle East and from Thailand and Australia to Hong Kong. Demand for meat is so great that Thailand's buffalo population has dropped from 7 million to 5.7 million head in the last 20 years, a period in which the human population has more than doubled.

Carcass Characteristics

All buffalo breeds-even the milking ones-produce heavy animals whose carcass characteristics are similar to those of cattle.

Despite heavier hide and head, the amount of useful meat (dressing percentage) from buffaloes is almost the same as in cattle. Mediterranean type buffalo and Zebu cattle steers in Brazil yielded dressing percentages of 55.5 and 56.6 percent respectively. Swamp buffalo dressing percentages have been measured in Australia at 53 percent.

Buffaloes are lean animals. Although a layer of subcutaneous fat covers the carcass, it is usually thinner than that on comparably fed cattle. Even animals that appear to be fat prove to be largely muscle. Australian research on Swamp buffaloes reveals that buffaloes with more than 25 percent fat are difficult to produce, whereas average choice-grade beef carcasses may contain

In general, the buffalo carcass has rounder ribs, a higher proportion of muscle, and a lower proportion of bone and fat than beef has.

Buffalo hide is so thick that it can be sliced into two or three layers before tanning into leather.

Meat Quality

Buffalo meat and beef are basically similar. The muscle pH (5.4), shrinkage on chilling (2 percent), moisture (76.6 percent), protein (19 percent), and ash (1 percent) are all about the same in buffalo meat and beef. Buffalo fat, however, is always white and buffalo meat is darker in color than beef because of more pigmentation or less intramuscular fat (2-3 percent "marbling," compared with the 3-4 percent in beef).

Eating Quality

Taste-panel tests and tenderness measurements conducted by research teams in a number of countries have shown that the meat of the water buffalo is as acceptable as that of cattle. Buffalo steaks have rated higher than beefsteaks in some taste tests in Australia, Malaysia, Venezuela, and Trinidad.

In taste-panel studies in Trinidad, cooked joints from three carcasses Trinidad buffalo, a crossbred steer (Jamaica-Red/Sahiwal), and an imported carcass of a top-grade European beef steer-were served. The 28 diners all had experience in beef production, butchery, or catering and were not told the sources of the various joints. All the carcasses were held in cold storage for one week before cooking. The buffalo meat was rated highest by 14 judges; 7 chose the European beef; 5 thought the crossbred beef the best; and 2 said that the buffalo and crossbred were equal to or better than the European beef. The buffalo meat received most points for color (both meat and fat), taste, and general acceptability. There was little difference noted in texture.( Information supplied by P. N. Wilson.)

Buffalo veal is considered a delicacy. Calves are usually slaughtered for veal between 3 and 4 weeks of age; dressed weight is 59-66 percent of live weight.

There is some evidence that buffaloes may retain meat tenderness to a more advanced age than cattle because the connective tissue hardens at a later age or because the diameter of muscle fibers in the buffalo increases more slowly than in cattle(Joksimonc, 1979) In one test the tenderness (measured by shearing force) of muscle samples from carcasses of buffalo steers 16-30 months old was the same as that from feedlot Angus, Hereford, and Friesian steers 12-18 months old. This gives farmers more flexibility in meeting fluctuating markets while still providing tender meat.

Selected Readings

Anonymous. 1976. Livestock Production in Asian Context of Agricultural Diversification. Asian Productivity Organization, Tokyo, Japan.

Arganosa, F. C., Sanchez, P. C., Ibarra, P. I., Gerpacio, A. L., Castillo, L. S., and Arganosa, V. G. 1973. Evaluation of carabeef as a potential substitute for beef. Philippine Journal of Nutrition 26(2).

Arganosa, F. C., Arganosa, V. G., and Ibarra, P. I. 1975. Carcass evaluation and utilization of carabeef. In: The Asiatic Water Buffalo. Proceedings of an International Symposium held at Khon Kaen, Thailand, March 31-April 6, 1975. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

Bennett, S. P. 1973. The "buffalypso"-an evaluation of a beef type of water buffalo in Trinidad, West Indies. Paper presented at the Third World Conference on Animal Production, Melbourne, Australia.

Borghese, A., Gigli, S., Romita, A., Di Giacomo, A., and Mormile, M. 1978. Fatty acid composition of fat in water buffalo calves and bovine calves slaughtered at 20, 28, and 36 weeks of age. In: Patterns of Growth and Development in Cattle: A Seminar in the EEC Programme of Coordination of Research on Beef Production, held at Ghent, October 11-13,1977. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, Netherlands.

Charles, D. D., and Johnson, E. R. 1972. Carcass composition of the water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Australian Journal of Agriculture Research 23:905-911.

Charles, D. D., and Johnson, E. R. 1975. Live weight gains and carcass composition of buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) steers on four feeding regimes. Australian Journal of Agriculture Research 26:407-413.

Cockrill, W. R. 1975. Alternative livestock: with particular reference to the wafer buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). In: Meat. Proceedings of the 21st Easter School in Agricultural Science, University of Nottingham, edited by D. J. A. Cole and R. A. Lawrie. Butterworth, London, England.

El-Ashry, M. A., Mogawer, H. H., and Kishin, S. S. 1972. Comparative study of meat production from cattle and buffalo male calves. Egyptian Journal of Animal Production 12:99-107.

El-Koussy, H. A., Afifi, Y. A., Dessouki, T. A., and El-Ashry, M. A. 1977. Some chemical and physical changes of buffalo meat after slaughter. Agriculture Research Review 55:1-7.

Johnson, E. R., and Charles, D. D. 1975. Comparison of live weight gain and changes in carcass composition between buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) and Bos taurus steers. Australian Journal of Agriculture Research 26:415- 422.

Joksimovic, J. 1979. Physical, chemical and structural characteristics of buffalo meat. Arhiv za Polloprivredne Nauke 22:110.

Joksimovic, J., and Ognjanovic, A. 1977. A comparison of carcass yield, carcass composition, and quality characteristics of buffalo meat and beef Meat Science 1:105 -110.

Mai, S. C., and Wu, T. H. 1974. TSC's intensive feed-lot system for cow-calf and beef production program. Taiwan Sugar 21(6):198-211.

Matassino, D., Romita, A., Cosentino, E., Girolami, A., and Cloatruglio, P. 1978. Myorheological, ohemical, and colour characteristics of meat in water buffalo and bovine calves slaughtered at 20, 28 and 36 weeks. In: Patterns of Growth and Development in Cattle: A Seminar in the EEC Programme of Coordination of Research on Beef Production, held at Chent, October 11-13, 1977. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, Netherlands.

Mogawer, H. H., El-Ashry, M. A., and Mahmoud, S. A. 1976. Comparative study of meat production from cattle and buffalo male calves. II. Effect of different roughage concentrate ratios in ration on carcass traits. Journal of Agriculture Research {Tanta University) 2:6-12.

Ognjanovic, A. 1974. Meat and meat production. In: The Husbandry and Health of the Domestic Buffalo, edited by W. R. CockrilL Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

Rastogi, R., Youssef, F. G., and Gonzalez, F. D. 1978. Beef type water buffalo of Trinidad-Beefalypso. World Review of Animal Production 14(2) :49 -56.

Romita, A., Borghese, A., Gigli, S., and Di Giacomo, A. 1978. Growth rate and carcass composition of water buffalo calves and bovine calves slaughtered at 20, 28 and 36 weeks. In: Patterns of Growth and Development in Cattle: A Seminar in the EEC Programme of Coordination of Research on Beef Production, Held at Chent, October 11-13, 1977. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, Netherlands.

Wilson, P. N. 1961. Palatability of water buffalo meat. Journal of the Agricultural Society of Trinidad 61:457, 459-460.

More than 5 percent of the world's milk comes from water buffaloes. Buffalo milk is used in much the same way as cow's milk. It is high in fat and total solids, which gives it a rich flavor. Many people prefer it to cow's milk and are willing to pay more for it. In Egypt, for example, the severe mortality rate among buffalo calves is due in part to the sale of buffalo milk, which is in high demand, thus depriving calves of proper nourishment. This also occurs in India, where in the Bombay area alone an estimated 10,000 newborn calves starve to death each year through lack of milk. The demand for buffalo milk in India (about 60 percent of the milk consumed; over 80 percent in some states) is reflected in the prices paid for a liter of milk: about 130 paisa for cow's milk compared with about 200 paisa for buffalo milk.

Twelve of the 18 major breeds of water buffalo are kept primarily for milk production (although males may be used for traction and all animals are eventually used for meat). The main milk breeds of India and Pakistan are the Murrah, Nili/Ravi, Surti, Mehsana, Nagpuri, and Jafarabadi. The buffaloes of Egypt, Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Romania, Yugoslavia, and the USSR), and Italy are used for milk production and there are also herds used principally for this purpose in Iran, Iraq, and Turkey.

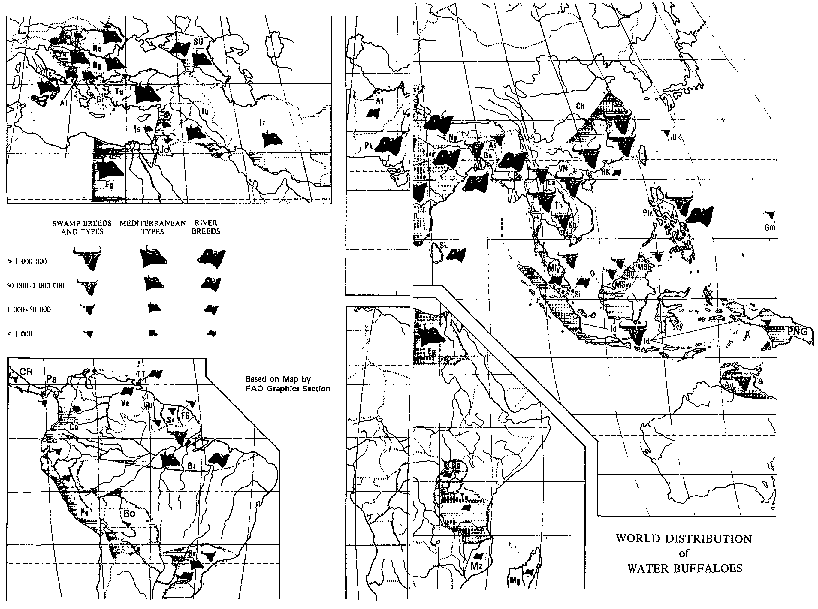

Composition

Buffalo milk contains less water, more total solids, more fat, slightly more lactose, and more protein than cow's milk. It seems thicker than cow's milk because it generally contains more than 16 percent total solids compared with 12-14 percent for cow's milk. In addition, its fat content is usually 50-60 percent higher (or more) than that of cow's milk. Although the butterfat content is usually 6-8 percent,( An analysis of 7,770 records of Nili/Ravi buffaloes in herds at the Pakistan Research Institute showed that average butterfat content was 6.40 (a mean based on 10 tests over 10 months). of all the samples tested, 77 percent ranged between 5 and 8 percent butterfat and 12 percent were below 5 percent butterfat. -information supplied by R. E. McDowell.) it can go much higher in the milk of some well fed dairy buffaloes and in the milk of Swamp buffaloes (which are not normally used for milking). Cow's milk butterfat content is usually between 3 and 5 percent.

Because of its high butterfat content, buffalo milk has considerably higher energy value than cow's milk. Phospholipids are lower but cholesterol and saturated fatty acids are higher in buffalo milk. Studies have shown that digestibility is not adversely affected by this. Because of the high fat content, the buffalo's total fat yield per lactation compares favorably with that of improved breeds of dairy cattle; it is much higher than that of indigenous cows.

Normally the protein in buffalo milk contains more casein and slightly more albumin and globulin than cow's milk. Several researchers have claimed that the biological value of buffalo milk protein is higher than that of cow's milk, but this has not yet been proved conclusively.

The mineral content of buffalo milk is nearly the same as that of cow's milk except for phosphorus, which occurs in roughly twice the amount in buffalo milk. Buffalo milk tends to be lower in salt.

Buffalo milk lacks the yellow pigment carotene, precursor for vitamin A, and its whiteness is frequently used to differentiate it from cow's milk in the market. Despite the absence of carotene, the vitamin A content in buffalo milk is almost as high as that of cow's milk. (Apparently the buffalo converts the carotene in its diet to vitamin A. The two milks are similar in B complex vitamins and vitamin C, but buffalo milk tends to be lower in riboflavin.)

Milk Products

Buffalo milk, like cow's milk, can provide a wide variety of products: butter, butter oil (clarified butter or ghee), soft and hard cheeses, condensed or evaporated milks, ice cream,yogurt, and buttermilk. It is of great economic importance in India in preparing "toned" milk-a mixture of buffalo milk and milk made by reconstituting skim milk powder.

The richness of buffalo milk makes it highly suitable for processing. To produce 1 kg of cheese, a cheese maker requires 8 kg of cow's milk but only 5 kg of buffalo milk. To produce 1 kg of butter requires 14 kg of cow's milk but only 10 kg of buffalo milk. Because of these high yields, processors appreciate the value of buffalo milk.

Buffalo cheese is pure white. It many countries it is among the most desirable cheeses (mozzarella and ricotta in Italy, gemir in Iraq, the salty cheeses of Egypt, and pecorino in Bulgaria, for example). In Venezuela all the cheese produced from the small La Guanota milking herd in the Apure River basin (about 100 kg a day) is bought by the Hilton Hotel and sells for 15 bolivars per kg compared with 8 bolivars per kg for cheese made from cow's milk.

Although much in demand for making soft cheese, buffalo milk is less desirable for making hard cheeses such as cheddar or gouda. During cheesemaking it produces acid more slowly than cow's milk, retains more water in the curd, and loses more fat in the whey.

Cheeses are becoming increasingly popular throughout the world. Demand is rising at a rate that is among the highest for any food product. Cheese offers particular benefit to areas where refrigeration is not widely available, where transporting high-protein foods to remote areas is difficult, and where seasonal fluctuations affect milk supplies. Buffalo milk may make cheesemaking profitable on an even smaller scale than conventional dairying; it is more concentrated than cow's milk and requires relatively less energy to transport and process (an increasingly important factor where fuels are limited).

Yield

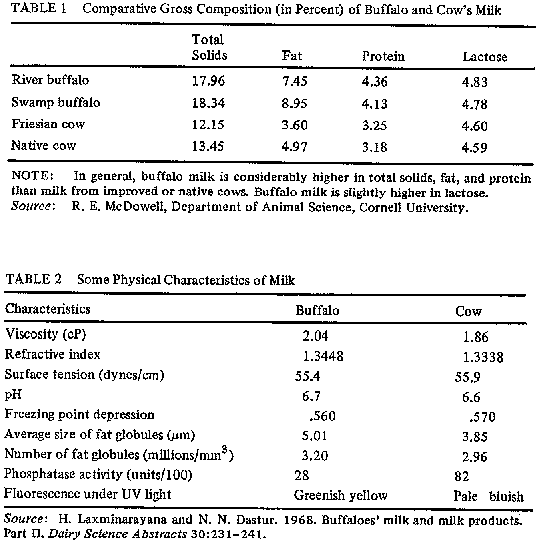

In countries like India and Egypt, the milk yield of buffaloes is generally higher (680-800 kg) than for local cattle (360-500 kg). However, since selection for exceptional milk production is not conducted systematically, large variations in yield occur between individual animals, and milk production of dairy buffaloes falls short of its potential.

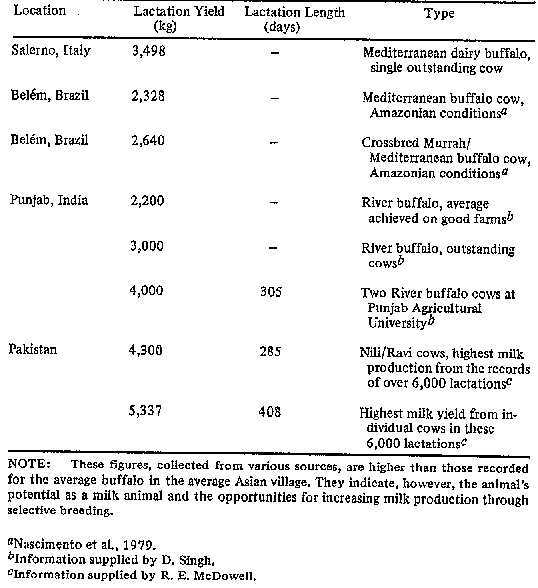

Nonetheless, some outstanding yields have been recorded. On Indian government farms, average yields for milking buffaloes range from 4 to 7 kg per day in lactations averaging 285 days. Daily yields of 12 kg have been reported for some Bulgarian buffalo cows and a daily production of over 20 kg has been reported for some remarkable animals in India. A peak milk yield of 31.5 kg in a day has been recorded from a champion Murrah buffalo in the All India Milk Yield Competition conducted by the Government of India (see Table 3).

At Caserta, Italy, a herd of 1,600 machine-milked, pedigreed dairy buffaloes has produced average yields of 1,500 kg during lactations of 270 days. In Pakistan an analysis of over 6,000 lactations of Nili/Ravi buffalo cows showed an average yield of 1,925 kg during lactations averaging 282 days(Average adjusted for year and season and calving. Cady et al., in press.) . In India the average milks yield of Murrah buffaloes in established herds is also reported to be about 1,800kg(*"Williamson and Payne, 1965.)Table 4 lists some outstanding lactation yields reported from different parts of the world.

As with cattle, the percentages of fat, protein, and total solids decrease as the milks yield increases.

The Swamp buffaloes of Southeast Asia are usually considered poor milk producers. They are used mainly as draft animals, but it may be that their milk potential has been underestimated. In the Philippines Swamp buffalo cows with nursing calves have produced 300-800 kg of milk during lactation periods of 180-300 days(*Philippines Council for Agriculture and Resources Research (PCARR). 1978. The Philippines Recommends for Caraboo Production, PCARR, Los Banos, Philippines)In Thailand Swamp buffaloes selected and reared for milk production have yielded 3-5 kg per day during 305-day lactations.(Information supplied by Charan Chantalakhana.)

The Nanning Livestock Research Institute and Farm in Kwangsi Province,which is representative of many others in South China, is upgrading the native Swamp buffaloes (or Shui Niu) by selective breeding for size and weight and by crossbreeding with dairy breeds such as the Murrah and Nili/Ravi. The crossbreeds that are milked yield 4-5 kg daily.(*CockriH, W. R. 1976. The Buffaloes of China. FAO, Rome.)

Dairy Management

The characteristics of the dairy buffalo so closely approximate those of the dairy cow that successful methods of breeding, husbandry, and feeding for milks production for the cow can be applied equally to the dairy buffalo. Buffaloes, however, have not been bred for uniform udders and it is more difficult to milk them by machine.(Some thousands of buffaloes are machine milked in Bulgaria and Italy, however. At Ain Shams University in Egypt, buffaloes have adapted to machine milking. The calves are separated from their dams immediately after birth and no problems of milk letdown have been observed. -information supplied by M. El Ashry.)Also, some buffaloes have more of a problem with milks letdown than dairy cows (although not as much of a problem as some native cattle breeds in the tropics). Frequently, a calf is kept with the cow and is tied to her foreleg at milking time. In India, Burma, and other countries a dummy calf may be provided; playing music seems to work, too.

Selected Readings

Addeo, F., Mercier, J. C., and Ribadeau-Dumas, B. 1977. The caseins of buffalo milk. Journal of Dairy Research 44(3):455-468.

Agarwala, O. P. 1962. Certain factors of reproduction and production in a water buffalo herd. Indian Joumal of Dairy Science 15(2):45-51.

Albourco, F., Mincione, B., Addeo, F., and Ameno, M. 1969. Buffaloes' milk. II. Variations in composition during lactation of milk produced without change in feeding. Industrie Agraria 7(5):210-219.

Associazione Italiana Tecnici del Latter. 1970. Buffaloes' milk and cheese. Scienza e Tecnica 21(3):175-196.

Bhatnagar, V. K., Lohia, K. L., and Monga, O. P. 1961. Effect of the month of calving on milk yield, lactation length and calving interval in Murrah buffaloes. Indian Journal of Dairy Science 14(3): 102-108.

Bhasin N. R., and Desai, R. N. 1967. Effect of age at first calving and first lactation yield on life time production in Hariana cattle. Indian Veterinary Journal 44:684694.

Cady, R. A., Shah, S. K., Schermerhorn, E. C., and McDowell, R. E. In Press. Factors affecting performance of Nili-Ravi buffaloes in Pakistan. Journal of Dairy Science.

Castillo, L. S. 1975. Production, characteristics and processing of buffalo milk. In: The Asiatic Water Buffalo. Proceedings of an International Symposium held at Khon Kahn, Thailand, March 31-April 6, 1975. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

Dassat, P. M., de Paolis, P., and Sartore, G. 1966. Environmental effects on milks yield in Italian buffalo.Acta Medica Veterinaria 12(6):587-593.

Dave, B. K., and Taylor, C. M. 1975. A study on relationship of persistency with other first production traits in Indian water buffaloes. Indian Journal of Animal Health 14(1) :77-80.

Deshmukh, S. N., and Choudhury, P. N. R. 1971. Repeatability estimates of some economic characteristics in Italian buffaloes. Zentralblatt fuer Veterinaer-medizen 18:104-107.

Ganguli, N. C. 1979. Buffalo milk technology. World Animal Review 30:2-10.

Gomez, I. V. 1977. The manufacture of semihard cheese (Danish type) from carabao milk. Philippine Agriculturalist 61(3/4) :78-86.

Gurnani, M., and Nagarcenkar, R. 1971. Evaluation of breeding performance of buffaloes and estimation of genetic and phenotypic parameters. Annual Report of the National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, India.

Katpatal, B. G. 1977. Dairy cattle crossbreeding in India. I. Growth and development of crossbreeding. World Animal Review 22: 15-21.

Kay, H. D. 1974. Milk and milk production. In: The Husbandry and Health of the Domestic Buffalo, edited by W. R. Cockrill. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

Kohli, M. L., and Malik, D. D. 1960. Effect of service period on total milk production and lactation length in Murrah buffaloes. Indian Journal of Dairy Science 13(3): 105-111.

Nascimento, C. N. B., Moura Carvalho, L. O. D., and Lourenco, J. B. 1979. Irnportancia do Bufalo para a Pecuarfa Brasileira. Agricultural Research Center for Humid Tropics (CPATU), Belem, Para, Brazil.

Raafat, M. A., El-Sayed, Abou-Hussein, Abou-Raya, A. K., and El-Shirbiny A. 1974. Some nutritional studies of colostrum and milk of cows and buffaloes E:gyptian Journal of Animal Production 14(1) :137-148.

Ragab, M. T., Asker, A. A., and Kamal, T. H. 1958. The effect of age and seasonal calving on the composition of Egyptian buffalo milk. Indian Journal of Dairy Science 11(1):18-28.

Saudi Arabia Standards Institution. 1978. Raw milk. Saudi Arabia Standard 98.

Sebastian, J., Panthulu, P. C, and Bhimasena, M. 1971. Composition of Surti buffalo milk. Annual Report of the National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, India.

Sekhon, G. S., and Gehlon, M. S. 1966. Repeatability estimates of some economic traits in the Murrah buffalo. Ceylon Veterinary Journal 14:18-22.

Singh, B. B., and Singh, B. P. 1971. Comparative study of lifetime economics of Hariana versus Murrah buffaloes. Indian Veterinary Journal 48:485-489.

Singh, R. P. 1966. A study of production up to ten years of age in buffaloes maintained at military farms. Indian Veterinary Journal 43:986-992.

Singh, S. B., and Desai, R. N. 1962. Production character of Bhadawari buffalo cow. Indian Veterinary journal 39:332-343.

Venkayya, D., and Anantakrishnan, C. P. 1957. Influence of age at first calving on the performance of Murrah buffaloes. Indian Journal of Dairy Science 10(1):20-24.

Williamson, G., and Payne, W. J. A. 1965. An Introduction to Animal Husbandry in the Tropics. Longman, London, United Kingdom.

The water buffalo is the classic work animal of Asia, an integral part of that continent's traditional village farming structure. Probably the most adaptable and versatile of all work animals, it is widely used to plow; level land; plant crops; puddle rice fields; cultivate field crops; pump water; haul carts, sleds, and shallow-draft boats; carry people; thresh grain; press sugar cane; haul logs; and much more. Even today, water buffaloes provide 20-30 percent of the farm power in South China, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and Indochina(Figures provided by A. J. de veer. In India water buffaloes contribute much less to farm power (6-12 percent); bullocks are more commonly used. In Pakistan buffaloes are little used for farm power (1-2 percent) but provide much of the road haulage. Papua New Guinea has no tradition of using any work animal, but villagers are increasingly using buffaloes for farm work and the government is employing Fillipinos to train them) . Millions of peasants in the Far East, Middle East, and Near East have a draft buffalo. For them it is often the only method of farming food crops.

As fuel becomes scarce and expensive in these countries, the buffalo is being used more frequently as a draft animal. ln 1979 water buffalo prices soared in rural Thailand because of the increased demand.

Although Asian farms have increasingly mechanized in the last 20 years, it has often proved difficult to persuade the farmer to replace his buffalo with a tractor since the buffalo produces free fertilizer and does not require diesel fuel. Now there is renewed official interest in draft power. Sri Lanka has recently opened up large new tracts of farmland in the Mahawali Valley, creating such a demand for work animals that buffalo shortages have become a national development problem. Indonesia's transmigration schemes are also handicapped by shortages of animal power.

For many small farmers the buffalo represents capital. It is often the major investment they have. Buffalo energy increases their productivity and allows them to diversify. Even small farms have work animals that, like the farmer himself, subsist off the farm. Tractors usually require at least four hectares for economical operation, which precludes their use on most peasant farms. Further, the infrastructure to maintain machinery is often not readily available.

Buffaloes are also used for hauling. Buffalo-drawn carts carry goods between villages where road surfaces are unfit for trucks. The animals easily traverse ravines, streams, paddies, and narrow and rocky trails. In the cities carts can compete economically with trucks where the road surface is unprepared, where loading or unloading takes longer than the journey itself, or where the loads are too small and distances too short to make trucking economical. For road haulage buffaloes are generally shod: the shoes are flat plates fitted to each hoof.

Capacity for Work

The water buffalo is a sturdy draft animal Its body structure, especially the distribution of body weight over the feet and legs, is an important advantage. Its large boxy hooves allow it to move in the soft mud of rice fields. Moreover, the buffalo has very flexible pastern and fetlock joints in the lower leg so that it can bend back its hooves and step over obstacles more easily than cattle. This water-loving animal is particularly well adapted to paddy farming because its legs withstand continual wet conditions better than mules or oxen(Australian animal scientists working in Bogor, Indonesia, found that the puddling effect of buffalo hooves on the soil was critical for rice cultivation in the local soils. Tractors produced fields so porous that they drained dry. (Information supplied by A. F. GurnettSmith.) On one research station near Darwin, Australia, buffaloes were used to prevent water draining from a dam. (Information supplied by D. G. Tulloch.).

Although buffaloes are preferred by farmers in the wet, often muddy lowlands of Asia, mules, horses, and cattle move more rapidly and are preferred in the dryer areas.

Water buffaloes do not work quickly. They plod along at about 3 km per hour. In most parts of Southeast Asia they are worked about 5 hours a day and they may take 6-10 days to plow, harrow, and grade one hectare of rice field. Their stamina and drawing power increase with body weight.

Because they have difficulty keeping cool in hot, humid weather (see next chapter), it is necessary to let working buffaloes cool off, preferably in a wallow, every 2 hours or so. Without this their body temperatures may rise to dangerous levels.

A pair of 3-year-old buffaloes costs about the same as a small tractor in Thailand. But many farmers raise their own calves and there is no investment beyond labor. The "fuel" for the animals comes mainly from village pastures and farm wastes such as crop stubble and sugarcane tops. Buffaloes have an average working life of about 11 years, but some work to age 20.

Harness

The yoke used on working buffalo in Asia has changed very little in the last 1,500 years. It is doubtful that a working buffalo can exert its full power with it. The hard wooden yoke presses on a very small area on top of the animal's neck, producing severe calluses, galls, and obvious discomfort. The harness tends to choke the animal as the straps under the neck tighten into the windpipe. Since the traditional hitch is usually higher than the buffalo's low center of gravity, the animal cannot pull efficiently. Considerably more pulling power and endurance can be obtained by improving the harness. The situation is not unlike that in Western agriculture in the twelfth century when the horse collar-one of the most important inventions of the Middle Ages first appeared. Before that, horses were yoked like buffalo and the harness passed across their windpipes and choked them as they pulled. Use of the horse collar improved pulling efficiency and speeded the development of transportation and trade.

The curved yoke now universally used on water buffalo contacts an area of the neck that is only about 200 cm2 (little more than half the size of this page). The entire load is pulled on this small area and causes the wood to dig into the flesh.

A horse collar is a padded leather device that encircles the animal's neck. One modified in Thailand for use on water buffalo (see page 43) had a contact area of 650 cm2, more than three times that of the yoke it replaced. The collar's padding pressed against the animal's shoulders, not its neck, and therefore did not choke it. Attached to the collar were wooden hames with the traces for hitching the animal to a wagon or plow. In trials a buffalo pulled loads 24 percent heavier with the collar than with the yoke, and the horsepower it developed increased by 48 percent(These trials were conducted by J. K. Garner in Thailand in 1958. In the maximum-load test the yoked buffalo failed to move a load of 570 kg, but it moved a load of 640 kg when fitted with the horse collar. In an endurance test the yoked animal took 35 minutes to pull a load 550 m, but harnessed with the collar it took only 21 minutes).

Another potentially valuable harness is the breast strap, a set of broad leather straps that pass over the animal's neck and back. One breast strap modified for water buffalo use had a contact area of 620 cm2, almost as much as that of the horse collar, and in trials the buffalo pulled a load 12 percent heavier than with a yoke and the horsepower it developed increased by almost 70 percent( The same animal used in the horse collar trials pulled 700 kg with the breast strap, in the endurance test it took 18.5 minutes to travel the 550-m distance).

These seem very good innovations. In the humid tropics, however, leather collars and breast straps may decay rapidly. To make them widely practical may require experimentation with, or development of, special leather treatments or more durable materials.

Selected Readings

Cockrill, W. R. 1974. The working buffalo. In: The Husbandry and Health of the Domes tic Buffalo, edited by W. R. Cockrill. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

Cockrill, W. R. 1976. The Buffaloes of China. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

de Guzman, M. R., Jr. 1975. The water buffalo-Asia's beast of burden and key to progress. In: The Asiatic Water Buffalo. Proceedings of an International Symposium held at Khon Kaen, Thailand, March 31-April 6, 1975. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

Garner, J. K. 1958 (Reprint 1980) Increasing the Work Efficiency of the Water Buffalo Through Use of Improved Harness. (Copies available from Office of Agriculture, Development Support Bureau, Agency for International Development, Washington, D.C. 20523)

Kamal, T. H., Shehata, O., and Elbanna, I. M. 1972. Isotope Studies on the Physiology of Domestic Animals. International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Austria.

Robinson, D. W. 1977. Preliminary Observations on the Productivity of Working Buffalo in Indonesia. Research Report No. 2, Center for Animal Research and Development, Bogor, Indonesia.

Vaugh, M. 1945. Report on a detailed study of methods of yoking bullocks for agricultural work. Indian Journal of Veterinary Science 15:186-198.

Ward, G. M., Sutherland, T. M., and Sutherland, J. M. 1980. Animals as an energy source in Third World agriculture. Science 208:570.

Heat Tolerance

While the buffalo is remarkably versatile, it has less physiological adaptation to extremes of heat and cold than the various breeds of cattle. Body temperatures of buffaloes are actually lower than those of cattle, but buffalo skin is usually black and heat absorbent and only sparsely protected by hair. Also, buffalo skin has one-sixth the density of sweat glands that cattle skin has, so buffaloes dissipate heat poorly by sweating. If worked or driven excessively in the hot sun, a buffalo's body temperature, pulse rate, respiration rate, and general discomfort increase more quickly than those of cattle(Failure to appreciate this has caused many buffalo deaths in northern Australia when the animals were herded long distances through the heat of the day as if they were cattle).. This is particularly true of young calves and pregnant females. During one trial in Egypt 2 hours' exposure to sun caused temperatures of buffalo to rise 1.3°C, whereas temperatures of cattle rose only 0.2-0.3°C.

Buffaloes prefer to cool off in a wallow rather than seek shade. They may wallow for up to 5 hours a day when temperatures and humidity are high. Immersed in water or mud, chewing with half-closed eyes, buffaloes are a picture of bliss.

In shade or in a wallow buffaloes cool off quickly, perhaps because a black skin rich in blood vessels conducts and radiates heat efficiently (Tests at the University of Florida have shown that buffaloes in the shade cool off more quickly than cattle. -Robey, 1976). Nonetheless, wallowing is not essential. Experience in Australia, Trinidad, Florida, Malaysia, and elsewhere has shown that buffaloes grow normally without wallowing as long as adequate shade is available.

Cold Tolerance

Although generally associated with the humid tropics, buffaloes, as already noted, have been reared for centuries in temperate countries such as Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and in the Azerbaijan and Georgian republics of the USSR. In 1807 Napoleon brought Italian buffaloes to the Landes region of southwest France and released them near Mont-deMarsan. They became feral and multiplied prodigiously in the woods and dunes of the littoral, but unfortunately the local peasants found them easy targets, and with the fall of Napoleon the whole herd was killed for meat(In the twelfth century Benedictine monks introduced buffaloes from their possessions in the Orient to work the lands of their abbey at Auge in northeastern France. In the thirteenth century a herd was introduced to England by the Earl of Cornwall, the brother of Henry III. Nothing is known about how well either herd survived). Buffaloes are also maintained on the high, snowy plateaus of Turkey as well as in Afghanistan and the northern mountains of Pakistan.

The buffalo has greater tolerance of cold weather than is commonly supposed. The current range of the buffalo extends as far north as 45° latitude in Romania and the sizable herds in Italy and the Soviet Union range over 40° N latitude(Philadelphia and Peking are at comparable latitudes. In the Southern Hemisphere the 40° line of latitude easily encompasses Cape Town, Buenos Aires, Melbourne, and most of New Zealand's North Island). Cold winds and rapid drops in temperatures, however, appear to have caused illness, pneumonia, and sometimes death. Most of the animals in Europe are of the Mediterranean breed, but other River-type buffaloes (mainly Murrahs from India) have been introduced to Bulgaria and the Soviet Union, which indicates that River breeds, at least, have some cold tolerance.

Altitude

Although water buffaloes are generally reared at low elevations, a herd of Swamp buffaloes is thriving at Kandep in Papua New Guinea, 2,500 m above sea level. And in Nepal, River buffaloes are routinely found at or above 2,800 m altitude.

Wetlands

Water buffaloes are well adapted to swamps and to areas subject to flooding. They are at home in the marshes of southern Iraq and of the Amazon, the tidal plains near Darwin, Australia, the Pontine Marshes in south-central Italy, the Orinoco Basin of Venezuela, and other areas.

In the Amazon, buffaloes (Mediterranean and Swamp breeds) are demonstrating their exceptional adaptability to flood areas. Buffalo productivity outstrips that of cattle, with males reaching 400 kg in 30 months on a diet of native grasses( Information supplied by C. Nascimento).

The advantage of water buffaloes over Holstein, Brown Swiss, and Criollo cattle was demonstrated in a test at Delta Amacuro, Venezuela, when the cattle developed serious foot rot In the wet conditions of the Orinoco Delta and had to be withdrawn from the test. The area of Venezuela is flooded 6 months of the year and creates constant problems for cattle, yet the buffalo seems to adapt well(*Information supplied by A. Ferrer).

High humidities seem to affect buffaloes less than cattle. In fact, if shade or wallows are available, buffaloes may be superior to cattle in humid areas.

In southern Brazil, trials comparing buffalo and cattle on subtropical riverine plains have favored the buffalo also. This work is being carried out on native pastures, mostly in the State of Sao Paulo.

Selected Readings

Hafez, E. S. E., Badreldin, A. L., and Shafei,M. M. 1955. Skin structure of Egyptian buffaloes and cattle with particular reference to sweat glands. Journal of Agricultural Science, Cambridge 46:19-30.

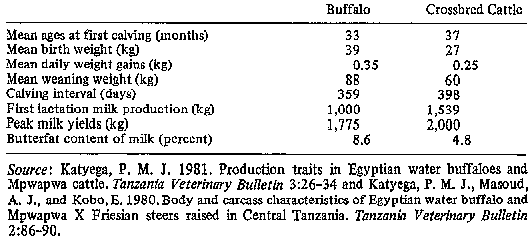

Katyega, P. M. J., Masoud, A. J., and Kobo, E. 1980. Information on body and carcass characteristics of Egyptian water buffalo and Mpwapwa x Friesian steers raised in central Tanzania. Tanzania Veterinary Bulletin 2:86-90.

Mason, I. L. 1974. Environmental physiology. In: The Husbandry and Health of the Domestic Buffalo, edited by W. R. Cockrill. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

Moran, J. B. 1973. Heat tolerance of Brahman cross, buffalo, Banteng and Shorthorn steers during exposure to sun and as a result of exercise. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 24(5) :775 -782.

Nair, P. G., and Benjamin, B. R. 1963. Studies on sweat glands in the Indian water buffalo. 1. Standardization of techniques and preliminary observations. Indian Journal of Veterinary Science 33:102.

Pandey, M. D., and Roy, A. 1969a. Studies on the adaptability of buffaloes to tropical climate. I. Seasonal changes in the water and electrolyte status of buffalo cows. Indian Journal of Animal Science 39:367.

Pandey, M. D., and Roy, A. 1969b. Studies on the adaptability of buffaloes to tropical climate. II. Seasonal changes in the body temperature, cardio-respiratory and hematological attributes in buffalo cows. Indian Journal of Animal Science 39:378.

Prusty, J. N. 1973. Role of the sweat glands in heat regulation in the Indian water buffalo. Indian Journal of Animal Health 12(1):33-37.

Robey, C. A., Jr. 1976. Physiological Responses of Water Buffalo to the Florida Environment. M.S. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA.

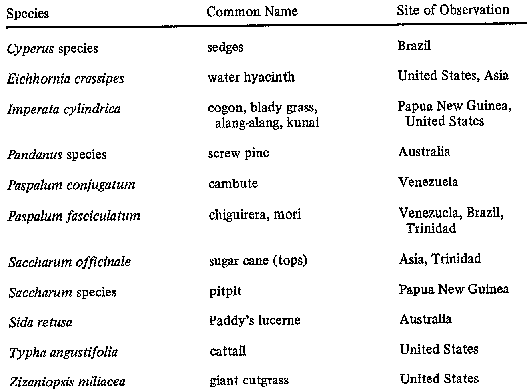

Most buffaloes are located in countries where land, cultivated forage crops, and pastures are limited. Livestock must feed on poor-quality forages, sometimes supplemented with a little green fodder or byproducts from food, grain, and oil seed processing. Usually feedstuffs are in such short supply that few animals have a balanced diet, but the buffalo seems to perform fairly well under such adverse conditions.

Growth Rate

Insufficient measurements have been taken to allow unequivocal state. meets about the relative growth rates of cattle and buffaloes. However, many observations made in various parts of the world indicate that the buffalo's growth is seldom inferior to that of cattle breeds found in the same environments. Some observations are given below.

· Trials in Trinidad in the early 1960s involved buffaloes grazing pangola grass (Digitaria decumbens) together with Brahman and Jamaican Red cattle. Over a period of 20 months the buffaloes gained an average of 0.72 kg per day, whereas the cattle on a comparable nearby pasture gained 0.63 per day(Experiments performed by P. N. Wilson. -Information supplied by S. P. Bennett.).

· In the Orinoco Delta of Venezuela unselected Criollo/Zebu crossbred cattle gained 0-0.2 kg per day on Paspalum fasciculatum, whereas the water buffaloes with them gained 0.25-0.4 kg per day(Cunha et al., 1975).

· In the Apure Valley of Venezuela, 100 buffalo steers studied in 1979 reached an average weight of 508 kg in 30 months, whereas the 30-month old Zebu steers tested with them weighed 320 kg. The feed consumed was a blend of native grasses (25 percent of the diet) and improved grasses (such as pangola, pare, and guinea grass)( Information supplied by A. Ferrer). In the same valley 200 buffalo heifers (air freighted from Australia) produced weight gains averaging 0.5 kg per day over a 2-year period (and 72 percent of them calved). Government statistics for the area record average weight gains in crossbreeds between Zebu and Criollo cattle as 0.28 kg per day (with 40 percent calving).

· In the Philippines, buffaloes showed weight gains of 0.75-1.25 kg per day, the same as those of cattle.

· Daily weight gains of over 1 kg have been recorded for buffaloes in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia.

· Liveweight gains of 0.80 kg per day have been recorded for buffaloes in Papua New Guinea. In a very humid, swampy area of the Sepik River coastal plains liveweight gains by males averaged 0.47 kg per day and females 0.43 kg per day for more than a year. The average weight of 30 4-year-old female buffaloes was 375 kg, while the average weight of 4-year-old female Brahman/ Shorthorn crossbred cattle was 320 kg.

· At the research station near Belem in the Brazilian Amazon weaned Murrah buffaloes, pastured continuously on Echinochloa pyramidalis (a nutritious grass), gained 0.8 kg daily and reached 450 kg in about 18 months.

· Liveweight gains of 0.74-l.i kg per day have been obtained in Australia. Buffalo steers grew as fast or faster than crossbred Brahman cattle on several improved pastures near Darwin, but on one very poor pasture, 40-year-old buffaloes each weighed only 400 kg, whereas the Brahman crossbred steers reared with them weighed 500 kg. The reason for this is not clear.

Efficiency of Digestion

Indian animal nutritionists have investigated water buffaloes intensively over the past two decades. Many have reported that buffaloes digest feeds more efficiently than do cattle, particularly when feeds are of poor quality and are high in cellulose.One trial revealed that the digestibility of wheat straw cellulose was 24.3 percent for cattle and 30.7 percent for buffalo. The figures for berseem (Trifolium alexandrinum) cellulose were 34.6 percent for cattle and 52.2 percent for buffalo. In another trial the digestion of straw fiber was 64.7 percent in cattle, 79.8 percent in buffalo.

Other nutrients reported to be more highly digested in buffaloes than in cattle (Zebu) are crude fat, calcium and phosphorus, and nonprotein nitrogen.

Recent experiments in India suggest that buffaloes also are able to utilize nitrogen more efficiently than cattle. Buffaloes digested less crude protein than cattle in one trial but increased their body nitrogen more (and they were being fed only 40 percent of the recommended daily intake of crude protein).

The ability of buffaloes to digest fiber efficiently may be partly due to the microorganisms in their rumen. Several Indian research teams have published data indicating that the microbes in the buffalo rumen convert feed into energy more efficiently than do those in cattle (as measured by the rate of production of volatile fatty acids in the rumen).