AFRICA-CARIBBEAN-PACIFIC - EUROPEAN UNION

Dossier

Communication and the media

Press freedom, regarded as a fundamental human right, is also a key component in the democratization process.

With the help of experts in the field, we look at what various organizations are doing to combat censorship and promote a free press in ACP countries and elsewhere.

We also highlight the new trend of donor support for projects aimed at promoting press freedom. These include, notably, provisions for the training of journalists. And as new means of communication, such as the World Wide Web, develop, we consider what is being done to prevent the opening up of a new divide - this time between the 'information rich' end the 'information poor'.

Country report

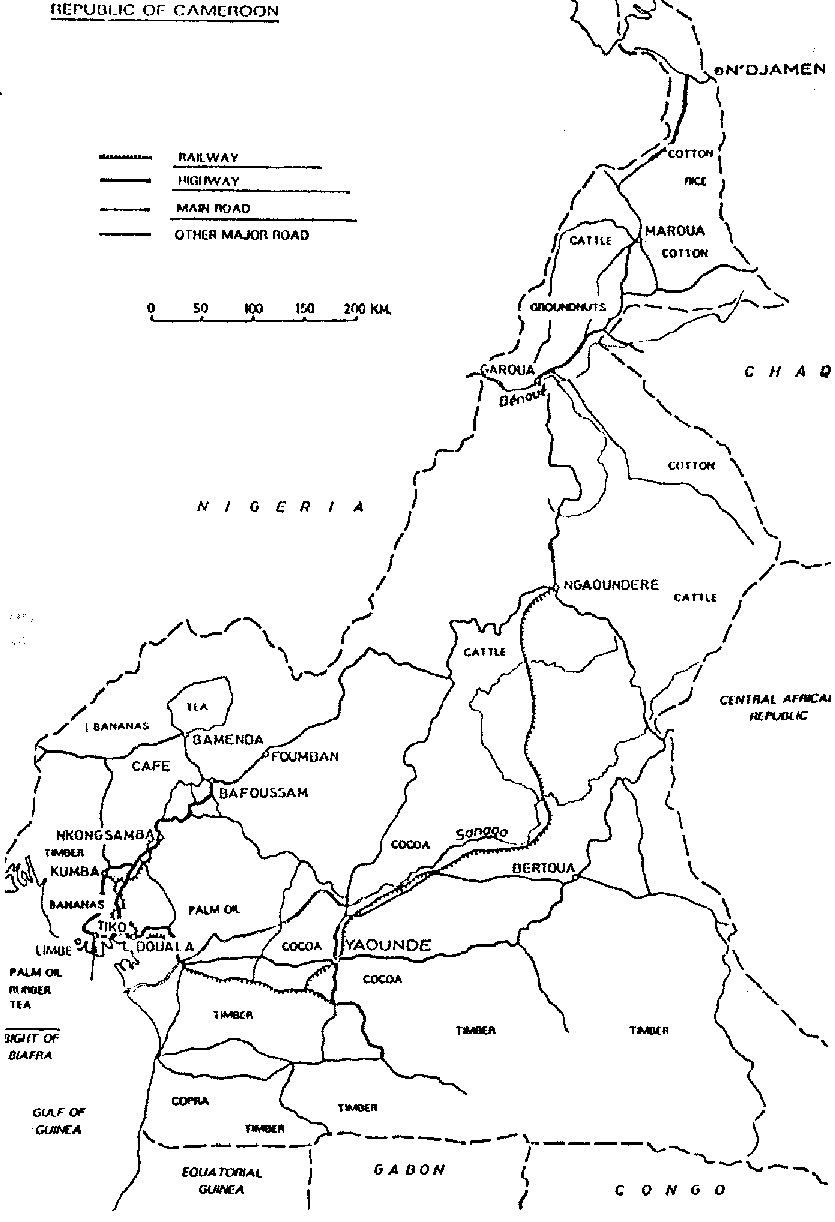

Cape Verde

Among the least-developed countries, Cape Verde is seen as a model of good governance and stable democracy. It is also admired for its perseverance in the struggle against the exigencies of history and climate. The country suffers from almost permanent drought and has virtually no regular supplies of fresh water.

Its history has been punctuated by serious famines and while the people are no longer hungry, they still face formidable economic difficulties.

Cape Verde produces just 10% of what it consumes and its exports are one fifteenth of its imports. The one bright spot is in services, where it enjoys a positive trade balance. This sector (in particular, international transport and tourism), together with the country's cultural industries, offer the best hope for future development.

'Combating attacks on press freedom

'Reporters sans frontières' was founded in June 1985 in Montpellier where Robert Ménard was working as a journalist with Radio France. Now based in Paris, RSF has two main policy areas. In the first place it alerts international public opinion and the media to situations involving violations of press freedom (via publications such as 'RSF News letter' the Annual Report and specific books and reports). Secondly, RSF actively intervenes by sending letters of protest to official bodies and assisting victims. Last year RSF dealt with more than 350 cases involving the press throughout the world. The organisation's ambition, according to Mr Ménard, is to be a kind of Amnesty International in the press field. The interview began with Mr Ménard giving a detailed description of RSF's work.

- We do two things - we report violations of press freedom and help journalists who are the victims of such violations. Take the former Yugoslavia, for example. It would have been unthinkable to monitor what was going on in that war-torn country without, at the same time, helping the media who were victims of the repression. So we sent over lawyers to help in trials involving the press, helped the families of imprisoned journalists and gave general assistance to the media. In the case of Oslabodenje, the Sarajevo daily, this went on for four years. We did similar work in Rwanda where RSF helped the media to get back on its feet after the genocide. In Algeria at the moment we are involved in aiding journalists who are obstructed when doing their work. We also give help in Europe - currently to refugee journalists in Belgium, France, Spain, Switzarland and Germany. That's basically what we do; reporting violations of press freedom and helping those who are the victims of it.

· Do you work with other organisations, for example the United Nations ?

- We work with various types of organisations. We have daily contact with other NGOs specialising in press freedom, such as Article 19 in London and the Committee for the Protection of Journalists in New York, to give just two examples. We also have contacts with NGOs involved in human rights issues in general and, above all, with Amnesty International.

Then there are our links with international organisations and, first and foremost, with the UN system. RSF has submitted reports in response to requests from various organisations, ranging from the UN Committee for Human Rights to UNESCO. We also work with the Council of Europe and the Organisation of African Unity. But our closest relationship is with the European Union, or two reasons; firstly because it is RSF's main financial backer and secondly Because the EU enables us to do three things. It has helped us set up and has Financed a vast network of correspondents in 130 different countries and, to my mind, this is the most important thing in terms of defending human rights and press freedom. We also publish reports, which we write in response to EU requests, on press freedom in one country or another and which are made available to the EU and European Parliament. Our third \ink comes in the form of assistance. We manage an aid fund to help where the press is in difficulties, and the money is provided by the Union.

-You have mentioned a network of correspondents which has been set up. How does it operate ?

- It is a network of people who are in daily contact with RSF and who tip us off when a situation requiring our attention arises. Whenever there is a violation of press freedom in a country where the network operates, our correspondent lets us know - that's the first priority. Then, they make enquiries at our request. The third stage is to set up events. For example May 3 was World Press Freedom Day and, on that day, in about 20 countries in Africa, our correspondents organised events on the theme of press freedom. A fourth aspect of our correspondents' work is that they are often responsible on the ground for helping journalists in difficulty. They also help the media in general because we give them documents and supply them with information which they distribute in their particular country. Their task, therefore, is to alert us to a situation, meet our requirements for information and, on our behalf, physically to assist people on the ground, set up events and disseminate information.

-Are the correspondents all nationals of the countries in which they work ?

- Yes. Also, about 90% of them are joumalists and they are all paid for what they do. Their relationship with us is clear-cut. It is very important for them to be paid because this means that we can ask certain things of them. If you work as a volunteer no-one can give you a deadline to produce such and such a document. In our case, we pay them to do this work for RSF.

· Do you choose countries where the situation is already problematic ?

- Unfortunately, problems exist in many countries. Less than half the countries in the world show any degree of respect for press freedom and that means we have a great deal of work. In addition, information arriving at RSF from the correspondents is distributed to other organisations. We have set up a system called Infex which is an electronic mailbox.

All RSF's information is put on a computerised system and immediately disseminated to all the organisations involved in the defence of human rights, and press freedom in particular.

· So the technological revolution is a positive thing as far as you are concerned ?

- Absolutely. Both the Imais and Internet systems are unbelievably useful tools which have completely revolutionised our work. For example, RSF might protest about the situation in some country or other. Take China, for example - we regularly lodge protests against the lack of press freedom there. There are 17 journalists in jail, no freedom for the press and a great many problems. However, people in China are not aware of what we do and in order to get information they have to listen to international radio stations. On the Internet, RSF's services are available in French, English and Spanish and it is consulted by people the world over. It is thus one of their sources of information. Another example would be a case where we set up an operation and inundate a number of people in a particular country with faxes, in order to pass on the information. Modern technology enables us to break down the fortresses which totalitarian or dictatorial regimes attempt to construct around themselves.

- RSF has just published its 1996 Report. What do you have to say regarding the current position of press freedom ? Has progress been made ?

- I would say two things. In the long term, the situation is improving. If you remember, 25 years ago, the regimes in half the countries in Latin America were dictatorships, communism dominated half of Europe and nearly all of Africa had single-party systems. Even in Europe, there were dictatorships - in Spain, Portugal and Greece. So we cannot deny that there has been progress. The problem is that, for three or four years now, there has been a noticeable rise in new threats to press freedom, and this is a great source of concern to us. Here I am thinking of the rise in power of fundamentalist movements, particularly religious fundamentalism. In a number of countries nowadays - the best example, or perhaps I should say the worst example, is Algeria - journalists are not only threatened by the state but are being killed by armed Islamic groups. The rise in religious fundamentalism is indeed a real danger.

The second type of threat confronting the press is the increased influence of mafia-type criminals. You will, of course, have heard about drug trafficking in places like Colombia or Peru. Nowadays, in some countries where communism has been overthrown, the big threat comes from these criminal gangs. Not so long ago in Russia, the star presenter on the main TV channel was killed because he got in the way of 'Mafia' interests.

The third threat comes from uncontrolled actions by groups fighting for autonomy or independence, like the Kurdish movement in Turkey (the PKK), and a number of separatist groups in India. The EU is no stranger to this either

- ETA poses a continual threat to the press, as do members of the FLNC in Corsica. It is only a few months since members of the latter group machine gunned a journalist's house. A fourth and new kind of threat, particularly in countries with a democratic system, comes from the rise of the extreme right.

Lastly, a point I draw particular attention to in our recent report is, in fact, a dual phenomenon. On the one hand there are states which pass laws under which any criticism is a crime and may lead to prosecution. An example of this is Egypt where the government has enacted a law which has led to charges being brought against some 60 journalists since summer 1995. On the other hand, there are states where justice simply does not operate and there is no will to make it function.

Last year, 51 journalists were killed and a number of others were attacked, but there has not been a single trial or conviction. It is a real culture of impunity. In some countries, the justice system either does not operate, or it is not independent. In such places, the authorities are reluctant to identify and prosecute those responsible for attacks on journalists.

· RSFcurrently has project running in Rwanda, in collaboration with the EU. Could you tell us something about this ?

- The EU is helping us to meet a wide range of needs in Rwanda, as well as in Burundi, where sadly, the situation is rather similar. In Rwanda, there are those who governed the country before the genocide and those in power at the moment. There was a specific problem there in that nearly half of Rwanda's journalists were killed during the genocide - 49 out of about 100. We had virtually to reconstruct the press system and the EU gave us the means to do this.The press currently has difficulties vis-à-vis the authorities but it is attempting to do its job. in Burundi, where our work is of a more conventional type, we see continuing attacks on press freedom. There, RSF is trying to resist the pressure, again supported by the EU. In fact, thanks to the EU, we are helping a number of countries' media to survive despite difficult conditions.

Another quite new problem is that before and during the genocide in Rwanda, the media were used as vehicles for disseminating hatred. They issued calls for people to kill their compatriots, in this instance the Tutsis, and the language they used was unbelievably violent. On Radio Mille Collines, presenters would say - and I quote; 'The graves are not full yet'. They would give out the addresses of people who had to be killed and when the murders had been carried out they would actually say, 'You killed them too quickly - you should have killed them more slowly to make them suffer more', or, 'You didn't kill the children, go back and kill the childreni. We actually have recordings of statements like this.

In such a situation, journalists must be made to answer for what they have done and be brought to justice.

The EU has helped us conduct a number of surveys which will enable the international criminal court in The Hague to charge Rwandan journalists with complicity or incitement to genocide. We expect this to take place in the very near future.

Of course in Rwanda, all that is in the past but the same thing is happening today in Burundi where there is a radio station called 'Radio Democracy' - what a joke! A number of journalists there are issuing calls for people to be killed and we have a copy of one of their newspapers whose front page offers a cash reward to anyone who kills such and such a person. This is not journalism. RSF has lodged complaints against these people and one of these 'journalists' has just been charged.

We are doing three things in Rwanda and Burundi: denouncing violations of press freedom by the authorities, helping media victims and - something new - reporting what has come to be known as 'the media of hatred'. Unfortunately, this type of media is not restricted to Rwanda and Burundi. it is a phenomenon that we see in a number of African countries, in the former Yugoslavia, the Caucasus and the

Middle East. Perhaps you are aware that the 50th anniversary of the Nuremberg trials has just passed ? But did you know that there were two journalists among the accused? The press has forgotten that journalists played a part in the rise of Nazism. RSF is pointing out that the same thing is happening today in many countries and we have to fight it.

'The EU is a perfect partner

· Given what you have just said, should restrictions be placed on press freedom ?

- This is a very complex subject. You have to remember that international texts, particularly the convention on civil and political rights, place restrictions on press freedom. Article 19, which defines press freedom, stipulates that there are certain limits to this and Article 20 forbids any dissemination of racist or antisemitic ideas and any incitements to violence.

RSF has two things to say. First, governments which have signed the agreements must ensure they are observed. These set limits. Journalists are not above the law and they must be punished when they say certain things. So states must face up to their responsibilities and apply the treaties they have signed. Second, I feel that the international community, and Europe in particular - when it signs agreements or gives aid to third countries - should demand that they respect press freedom but clamp down on the media of hatred.

· RSF has just published a draft model legislation governing the press. In preparing this, were you influenced by your experience of the extremist media ?

- Perhaps we were influenced too much. I am my own worst critic. We sent a mission to Rwanda before the genocide but did not appreciate the full effects of the evil disseminated by the media of hatred, particularly Radio Mille

Collines. We underestimated the situation and are concerned at what is happening. We believe there must be express limits on press freedom and this draft framework law is one way of formulating such restrictions. It is not necessarily the best way of going about things, but our profession has to ask itself questions regarding the definition of press freedom and the limits we must not exceed.

· Are you satisfied with what the EU is doing in this area ?

- The EU is a perfect partner and has never exerted any pressure. With the Union, we are able to do things that would not be possible with individual Member-State government because the latter conduct foreign policy in defence of certain interests. Each country has its own cultural history linguistic links or links arising out of former colonial times which prevent it financing RSF's studies unconditionally. As far as our missions are concerned, RSF decides what it wants to do and we send our reports to the EU. They have also granted us a budget enabling us to give immediate aid to people in difficulty. This is the most positive action possible If the EU were not there, there would unfortunately be no-one else to finance an organisation like ours. 60% of our budget comes from the Union, 20%from various companies. We generate the remaining 20% ourselves through sales of books and contributions. Because the EU is a grouping of governments, the Commission has some room for manoeuvre. This is the only possible kind of support for organisations like RSF and, if it were not there, it would be the end for the people whom RSF supports. interview by Dorothy Morrissey

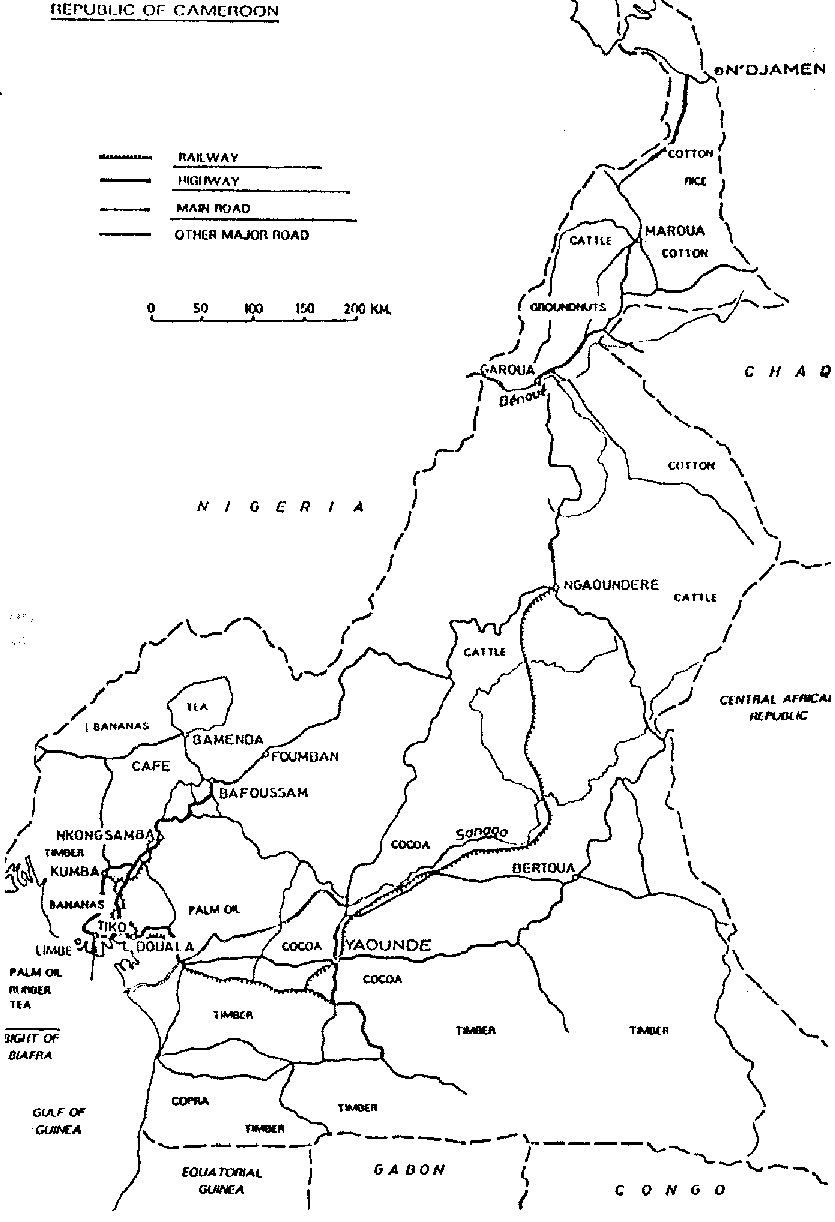

It is an astonishing sight to behold during the rainy season. As you drive along the road from Yaoundé to Bamenda, you come to a point where human habitation starts - and it then continues unbroken for more than 100 kiLométres. Just before Bafoussam, and as far as the eye can see, every patch of land is cultivated. Bananas, oranges, mangoes, sugarcane, cassava, palm trees, groundnuts and maize grow luxuriantly in open fields and in the front and back gardens of many houses. This route, of course, takes you mainly through the western part of Cameroon, home to the Bamilelrés, recognised as one of the country's most enterprising and industrious ethnic groups. The population density here is 200 per km2 as opposed to 1 per km2 in the East.

The impact of this widespread farming, carried out by a large number of smallholders, is visible in the local markets, whether in Bafoussam, Mbouda or Bamenda. There, the stalls overflow with fruits and vegetables and prices are very low - a virtual paradise for the middlemen whose unmistakable presence is signalled by the significant number of trucks loading the produce for distribution throughout the country.

These scenes come as no surprise to the long-time observer of Cameroon's economy. The country achieved virtual self-sufficiency in food over 15 years ago. It is one of the few African countries to have been able to do this, thanks both to its physical endowments and an early recognition of its agricultural vocation.

Cameroon is often described as a microcosm of Africa, not just in terms of its make-up of English- and French speaking communities, but because it enjoys almost all the continent's climatic conditions. The south is equatorial, with two rainy seasons and two dry seasons of equal duration, the centre is Savannah country with one rainy season and one dry season, while the extreme north (part of the Sahel) is hot and dry. The country has a very good supply of rainfall - from 5000 mm annually in the southwest to around 600 mm near Lake Chad.

Such varied climates favour the cultivation of a variety of crops. Timber is produced mainly in the southern provinces while palm oil, tea, cocoa, coffee, rubber, timber and foodcrops are produced in the southwestern and western areas. The central and north provinces specialise in cattle and cotton production.

Concentration on agriculture

Cameroon has, not surprisingly, concentrated on agriculture. Indeed the government has given top priority to the sector in all its development plans since independence in 1960. It has been involved in the marketing of the main export crops and has provided subsidies to farmers in the form of low-priced fertilisers and pesticides for their cocoa, coffee, rubber, palm oil, etc. Almost three-quarters of the working population (the majority of whom are smallholders) are engaged in farming. And despite a low level of mechanisation, they are very efficient. The rate of growth in food outstrips the rate of population growth. Only a few largescale farmers or firms are involved in the production of cash crops.

Until the early 1980s, when oil came into the picture, these large scalefarmers and firms amounted for more than 70% of export earnings, 40% of state revenue and 32% of the Gross Domestic Product. The plan initially was to use oil revenues to further boost and transform agriculture. However, the dramatic increase in the country's oil production, combined with much higher world petroleum prices during the first half of the 1980s, made the sector not only Cameroon's biggest export earner, but also, in a certain sense, a 'spoiler' for agriculture. Increased revenues enabled the government to maintain the level of prices paid to farmers, even though world prices had slumped to disastrous levels. This created distortions in the market. (Later, when the oil price slumped, and revenues dropped sharply, producer prices were also reduced, bringing them closer into line with international prices.)

Agriculture's contribution to GDP declined steadily to around 21 % in 1985, rose to 27% in 1989 and has hovered around 30% ever since. The sector's share of export earnings has also fallen to about 40% of total exports by value.

Despite this, Cameroon's agriculture remains, comparatively, in a much better shape than that of most African countries. Indeed, it contributed in large measure to the country's reputation as one of Africa's economic successes in the 1980s. During that decade, growth averaged 8% per annum. However, the period was also marked by dramatic increases in oil revenues which induced significant policy changes as well as leading to maladministration. The government paid less attention to taxation and customs duties as sources of income and turned a virtual blind eye to smuggling which harmed the manufacturing sector. The civil service, on the other hand, expanded beyond reason, a phenomenon that some have attributed to patronage by the ruling single party.

Boom in public expenditure

Protected somewhat against fluctuations in earnings from export crops, by a strong but overvalued CFA franc, the government embarked on a wide range of capital expenditure and imports. Then, in 1987, international oil prices fell as dramatically as they had risen earlier in the decade. At the time, public spending was running at CFAF 8 billion - well above the CFAF 5.6bn the country actually earned. Revenues from oil continued their downward slide to CFAF4.5 bn in 1988, CFAF 2.8 bn in 1991 and CFAF 2.5 bn in 1994. 1995 saw a modest rise to CFAF 3 bn.

1987 thus marked the beginning of a rapid deterioration in Cameroon's financial situation. In the period which followed, civil servants' salaries were unpaid for months, several of the country's foreign missions were left without resources and both domestic and foreign debts worsened. In 1993, the government owed commercial banks around CFAF 3.3bn. Its external debt stood at around $7.5bn with a service ratio of more than 25% of foreign exchange earnings. The devaluation of the CFA franc in January 1994 improved the internal debt situation significantly. In February, the government signed a letter of intent with the IMF after agreeing to a series of reforms which included, among other things, rationalising the banking and insurance sectors, raising revenue from non-oil sources, bringing inflation down and reducing the budget deficit. In return the IMF provided a stand-by loan equivalent to CFAF 1.4bn. However, the agreement was suspended just a few months later when the Fund reached the conclusion that the government lacked the will to carry the reforms through. The 1994/95 budget foresaw a deficit of 4.5% of GDP - well above the IMF's guideline of 1.5%.

Meanwhile the country's financial situation had become so critical that it could no longer service its debts, most notably, those it owed to the World Bank. France, which had traditionally been ready to come to the rescue, refused to bail Cameroon out and it finally dawned on the authorities that structural adjustment was unavoidable. When, in September 1995, talks resumed with the IMF, the commitment to adjustment was no longer in doubt. The government agreed, in addition to fiscal reforms, to liberalise trade in cocoa, coffee and timber, to prune the civil service and to privatise state enterprises which dominate the industrial sector.

Commitment to reforms

Since then the reform process has been in full swing. The first and most important task has been to improve the government's financial position. The civil service, which employs more than 175000 people, is gradually being reduced and salaries have been cut. Trade is also being liberalised and subsidies are being removed. The 1995/96 budget, unveiled in June last year, was welcomed by the IMF. It included, for the first time in a long while, increases in income tax and a widening of tax bands. A series of measures have also been introduced to combat tax evasion and fraud. External signs of wealth, water and electricity consumption, and telephone bills are now being used as means of assessing income tax.

Responsibility for the collection of customs duties has been removed from the Customs Department which was often accused in the past of corruption and inefficiency. The task has been given instead to a Swiss-based preshipment inspection company.

The donor community has responded positively. With French assistance, the government has been able to clear its outstanding debt to the World Bank. The IMF has provided a stand-by credit facility of $101 million in support of the adjustment programme for 1995/ 96 and debts to the Paris Club covering the same period have been rescheduled. In addition, now that Cameroon has been reclassified as a poor country, it is entitled to benefit from the terms of the Naples Agreement, which allow for up to 67% of debts to western govemments to be written off. A number of creditor nations have either forgiven the country its debts or have reduced them substantially. More loans have come from France and a number of other donors, including the World Bank and the European Community.

The EC is financing a series of projects within the framework of the adjustment programme, including the restructuring of the civil service and preparation of the ground for privatisation.

Lately though, the donor community has been showing signs of disenchantment, following allegations of misuse of funds and perhaps even outright embezzlement. Last March, an IMF mission to Yaoundé failed to obtain an adequate explanation concerning the allocation of certain sums. The result, at the time The Courier went to press, was that an IMF loan for settlement of Cameroon's debt to the African Development Bank was being held up.

Dealing with the negative social impact

The sudden devaluation of the CFA franc in January 1994 halved Cameroon's purchasing power overnight. The government has since cut wages twice. The average salary of a top civil servant, which stood at around CFAF 300 000 before devaluation, is now less than CFAF 180 000 while the lowest paid government employees receive just CFAF 30 000. At the same time, prices, particularly of imported manufactured goods and inputs, have risen sharply. Increases of up to 150% have been recorded. By way of example, the price of a baguette (french bread), which was only CFAF 80 in January 1994 had risen to CFAF 130 by March 1996.

Although there is considerable hardship, Cameroonians are a great deal more fortunate than fellow Africans in many other countries undergoing a similar adjustment process. Staple food remains cheap and affordable to the vast majority, thanks to the continuing strength of agriculture. As a result, there are few, if any, cases of malnutrition.

A number of donors, including China, Belgium and the EC, are concentrating on health and education with the specific aim of reducing the negative social impact of adjustment. The EC, for example, has a project designed to strengthen health provision at the grassroots. This entails rehabilitating infrastructures (health centres and district hospitals in particular) and establishing medical supply centres in areas that are not covered by other donors. The project is governed by the principle of cost-recovery to ensure viability and sustainability. But one area where the donors cannot do much is in the field of job creation. There is growing unemployment and job prospects in the formal sector, at least in the short term, are not good.

In macro-economic terms, things are locking up slightly for Cameroon. After recording economic growth of 3% in 1994/95, the hope is for a 5% increase in 1995/96. However, Cameroon's main economic operators, grouped under the umbrella of GICAM (Groupement inter-patronal du Cameroun), expressed fears late last year that the country would not achieve this level of growth.

Cameroon exports a variety of primary commodities, most of whose prices have recovered in recent years, and devaluation has had a positive impact on the country's balance of trade. Specifically, it has helped make exports more competitive and in 1994/ 95 the trade surplus was a healthy CFAF 349bn, almost double the CFAF 128bn recorded in the previous year. There was a noticeable slowdown in the export of timber in the latter half of last year and the qualities of coffee and cocoa being sold were not up to the usual standard, a situation that led to both crops being shunned in the world market. Bananas exported to France were also meeting stiffer competition from French Caribbean bananas. However, the fact that rubber production has risen by more than 10%, while aluminium output and sales have increased, should help Cameroon to record another positive trade balance when the figures are next published.

The forestry sector, which has huge foreign-exchange earning and employment potential, is being rationalised as part of the current structural adjustment programme. The Canadian Agency for International Development

(CAID) has a five-year project to conserve and regenerate some 30 000 hectares. In fact, half of Cameroon is covered by forest and less than 500 000 ha is currently being exploited. The objective is to ensure that forest resources are exploited in the future at a sustainable level.

The private sector

Industry, which is still in its infancy, has been developed by the government since independence largely with a view to import-substitution, although with some gearing towards the regional market. It accounts for about 14% of GDP and is currently dominated by aluminium smelting. Although devaluation has lately improved the competitiveness of those enterprises that add value to locally available raw materials, the manufacturing sector as a whole faces two major challenges now that the government has accepted the idea that the economy is best driven by the private sector.

The first relates to private investments, which have been sluggish over the past ten years; a clear illustration of a lack of confidence in the economy. This was amply demonstrated when Cameroonians with funds abroad failed to repatriate them to take advantage of the CFAF devaluation as was widely expected. This phenomenon puts the whole privatisation exercise in jeopardy as it means that the government is more likely to have to rely on foreign entrepreneurs. The best the authorities can therefore expect in the short term, some observers say, is to convert those state enterprises that are not already joint-ventures into ones where private investors become the majority shareholders. Complete divestment will then take place gradually over a longer timescale. Overall, 150 state enterprises have been earmarked for sale.

According to André Siaka, director of Cameroon's Brewery, who is also Chairman of GICAM, another reason for the lack of investment was high interest rates. These hovered around 20% for many years. Even now, after the reform of the banking sector, interest rates remain very high and there are no borrowers, he told The Courier.

Donors again have been conscious of this and some of their interventions have reflected this concern. For example, Canada is providing funds for the establishment in Douala (the commercial capital) of a centre for the development of private enterprises. Meanwhile, the Chinese have promised to provide CFAF 7bn to enable a line of credit to be opened for small and medium sized enterprises.

The government itself is puting in place a number of incentives, according to Minister of Trade and Industry Eloundou Mani Pierre. The liberalisation of the economy and the reform of the customs regime in collaboration with UDEAC, to which Cameroon belongs, are part of these. Mr Mani told The Courier that with a population of under 12 million, Cameroun's most important market was Central Africa. He also, perhaps surprisingly, has high hopes for the new World Trade Aareement.

Cameroon meanwhile is reviewing its plan for the establishment of export processing zones with the help of its main donors.

It is also looking at other ways of attracting foreign investment, particularly in 'value-added' enterprises involved in the processing of locally available raw materials such as cotton, cocoa, coffee and timber.

Social and political peace

The second, and by far the more serious challenge facing manufacturing, is the problem of large-scale smuggling by petty traders.

Evidence of this abounds in the booming central market of Douala, where goods of all kinds can be found at very reasonable prices. Ironically the measures which were being taken and judged to be relatively effective against smuggling in recent years have had to be abandoned under structural adjustment rules imposed on the government.

As Mr Siaka pointed out, petty traders dealing in smuggled goods put pressure on enterprises, 'because they do not pay tax', and threaten to render domestic manufacturing uncompetitive. It is also widely acknowledged, however, that the small-scale traders, who dominate the informal sector, provide job opportunities to Cameroonians, which is important at a time of economic austerity. Indeed petty trading has arguably been the safety-valve, helping to ease the social pressures brought about by structural adjustment, and thus preventing civil unrest.

But the extent to which that safety-valve can withstand the emerging political pressures is a different matter. Democratisation, understandably, was one of the conditions imposed by donors for assistance to Cameroon. After a series of elections - presidential, legislative and municipal - which were marred by violence and deaths, there are still doubts about the health of democracy in the country. Indeed, there are signs that tension is mounting. And few would dispute that if Cameroon is to succeed economically, it needs both social peace and political stability.

Augustin Oyowe

by Alex Kremer

Commission President's visit to West Africa

The European Union's commitment to regional development in sub-Saharan Africa is as strong as ever, but sustainable development can only come from Africa's own initiative. This was the message delivered by Jacques Santer, President of the European Commission, in his address to African heads of state at the UEMOA (Economic and Monetary Union of West Africa) summit in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, on May 10.

'I wish to emphasise from the start,' Mr Santer declared to the Presidents of Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'lvoire, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo, 'that the European Commission and the European Parliament are both determined to make our partnership even more dynamic and in tune with today's rapidly changing world.'

The presence of the Commission President at the UEMOA summit marks a milestone in the European Community's support for regional integration in the developing world. With its own Commission, Council of Ministers and Court of Justice, the UEMOA appears to be consciously following the supranational model of regional integration pioneered by the European Union.

The sequencing of UEMOA integration, however, is almost the reverse of the European model. Already linked by a single currency in the CFA franc, the West African Union's member states are now pressing ahead with plans for integration of their 'real' economies. The implementation timetable agreed in Ouagadougou covers freedom of establishment, free movement of capital, mutual macroeconomic monitoring and the first steps to customs union with the harmonisation of external tariffs and the lowering or removal of intra-regional barriers to trade.

President Santer indicated that the European Commission is keen to discuss how the European Development Fund (EDF) can support these initiatives. Such aid could take the form of technical assistance and training as well as direct budgetary support to mitigate the short-term costs of customs union.

UEMOA is not, however, an aid project. Its member states have designed it to stand on its own feet financially from the start. A 'community solidarity levy' was due to come into effect on 1 July 1996. The money will be used for a structural fund programme beginning in late 1997, as well as to finance the Union's operating costs.

Meeting with the President of Burkina Faso, Blaise Compaoré, Mr Santer said that it was particularly significant that his first official visit to Africa as President of the European

Commission was to Ouagadougou. Not only was it a reaffirmation of the partnership between Africa and the EU, and a statement of the EU's willingness to support regional integration in the developing world. It was also a tribute to the determination of the people of Burkina Faso and other African countries to promote their own development.

The European Community is Burkina Faso's second largest donor, contributing 10% of total aid payments in 1994. Since 1991, the EC has committed an average of ECU 45 million each year to development cooperation with this country, rising to a peak of ECU 100m in 1995.

Mr Santer visited the EDF-financed road improvement site at Tougan, close to the frontier with Mali, and noted that intra-regional transport links were an essential complement to the legislative programme of the UEMOA. He concluded his tour of regional cooperation projects with a visit to a photovoltaic pumping system financed by the EC under its West African solar energy programme.

Finally, on a more personal note, the Commission President was able to drop in on a project managed by the charity Chrétiens pour le Sahel. Mr Santer worked for this Luxembourg-based organisation before starting his career in politics and he was visibly pleased to see that it was still going strong - supporting home-grown African initiatives with a little financial help from the European Community.

A.K.

When the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) was inaugurated 11 years ago in Ede, Prince Claus of the Netherlands - whose interest in development issues is well-known - attestded as guest of honour. On 19 April, he returned to take part in the official opening of the CTA's new building in neigh bouring Wageningen in the Dutch province of Gelderland. The siting of the purpose built premises is significant. The town of Wageningen has long been an important European centre for agricultural research and the Dutch, of course, are renowned for their commitment to cooperation with developing countries.

The CTA may only have moved a short distance from its previous headquarters, but the Centre's 38-strong staff are also aware of the need to move with the times when it comes to fulfilling their role in the field of agricultural information. This point was particularly emphasised by CTA Director, Dr. R.D. Cooke in his presentation at the opening ceremony. Recalling the Centre's main tasks (see box) Dr Cooke spoke of the 'changing horizons and challenges' which they faced, and he focused on four specific aspects.

The first of these is the big change taking place in national agricultural systems, with the state withdrawing more and more in favour of the private sector and NGOs. This is being accompanied by a trend towards decentralisation with the result that the CTA has many more potential partners to cater for and work with.

Global liberalisation has also had an effect on the kind of information being sought by the CTA's 'customers'. In the past, demand was almost exclusively for scientific or technical information, notably aimed at increasing productivity. Dr Cooke reported that while this remained important, there was now an increasing interest in marketing and socio-economic aspects to facilitate decision-taking.

It came as no surprise to hear the Director highlight the challenge posed by new technologies such as electronic networking and digital storage. The key point here, he stressed, was to find ways of adapting these to ACP needs and realities. 'In the next century,' he argued, 'the haves and the heve-nots will be defined by their access to information.'

Finally, Dr Cooke referred to the growing significance of regional linkages. He indicated that the CTA was locking at ways in which it could help its partners to devise regional development programmes.

The declaration signalling the official opening of the building was made in the preceding presentation by E.F.C. Niehe who is Deputy DirectorGeneral for European Cooperation at the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In his speech, Mr Niehe emphasised the relevance of the CTA, pointing out that while the world food situation had improved, 'we are now on the threshold of structural food insecurity'. He also spoke in more general terms about the future of ACP-EU cooperation and acknowledged that 'partnership, sovereignty and equality had been somewhat neglected' by donors. However, he suggested that these concepts were now 'coming back'.

From the ACP side, the Swaziland ambassador, CS. Mamba,who is co-President of the Committee of Ambassadors, took up the theme of food shortages in sub-Saharan Africa and identified some of the difficulties encountered by African producers, particularly in respect of new technologies and marketing. He also referred to the environmental challenges facing ACP countries, especially in the Caribbean and Pacific. He was keen, however, to stress that the picture was 'not entirely negative'. Thus, for example, new technologies and methods had had a positive impact on grain production in Zimbabwe, horticulture in Kenya, and cocoa and coffee in West Africa. Mr Mamba echoed Dr Cooke in stressing the advantages of regional markets, and concluded with a firm statement of support for continuing ACP-EU cooperation.

'History,' he said, 'will show that the Lomé Convention played a central role in the momentum of development.'

The final speaker was Steffen Smidt, Director-General for Development at the European Commission, who suggested that the CTA had played a pioneering role in developing a sectoral approach at a time when the focus of development cooperation tended to be on individual projects. 'The Centre', he said, 'has become a well-respected international institution in the field of agricultural information.' The Director General focused on the need for ACP countries to develop their own capacities and on the gap that exists 'between potential and reality', because of capacity limitations. The Centre, he believed, could 'help bridge this gap.' Mr Smidt also reiterated a point made earlier that the information flow should not just be in one direction. 'Information from South to North is vital,' he argued, to ensure better targeting of programmes in future.

After the speeches, guests had an opportunity to learn more about the CTA's work by speaking to the Centre's personnel and visiting a special exhibition illustrating the nature and purpose of the Centre's activities. _

Simon Homer About the CTA

The CIA's tasks are:

- to develop and provide services which improve access to information for agricultural and rural development ;

- to strengthen the Opacity of ACP countries to produce, acquire, exchange and utilise information in these areas.

Programmes are organised around three principal themes:

Strengthening information centres - designing strategies for improving agricultural information services; - promoting use of new information technologies; - providing training; - donating books.

Promoting contact and exchange of: experience among CTA's partners in rural development - seminars; - study visits.

Providing information on demand - publication s; - radio and audiovisual materials; - literature services for researchers; - Question and answer service.

(The address of the Technical Centre for Agriculture and Rural cooperation can be found in the CTA section towards the end of the white pages in this issue.)

By Martin Dihm

What do the Windward Islands' banana industry and Hamlet have in common ? Both are intrigued by the same question: 'To be or not to be.' But unlike Hamlet, whose fete was decided rather quickly and tragically, the future of Windward Canibbean banana production is still open. And what is more, Windward producers have a distinct advantage over Hamlet. They can hire consultants to analyse their problem and come up with fresh solutions. That is what has happened. But before turning to the solutions, what have the problems been ?

The four Windward Islands; Dominica, St Lucia, St Vincent and Grenada, have long enjoyed preferential market access to the UK. This first permitted the creation of the industry and then secured its survival, even with production costs that are much higher than those of other producers.

A traumatic moment came when the European Community had to decide on a common market regime for bananas. Coming into effect in mid 1993 the regime maintained the principle of preferential access for traditional ACP producers. Nevertheless, it introduced a move towards greater market liberalisation. Fierce attacks on the regime by certain of the EU's trading partners have raised doubts about its viability. The system is due, in any case, to expire in 2002 when even further liberalisation seems likely.

All this could cause great difficulties for the Windward Islands which still depend substantially on banana exports to the EU. A decline in prices since mid-1993 and the appearance of new competitors in the previously protected UK market have further underlined the need for the Windwards to compete in a more liberal arena. The Islands commissioned a study, funded by the UK and the EC, into the competitiveness of their industry and on ways of improving its position. It was not the first study of this type, but earlier ones had had no real impact on the industry which had always been sufficiently protected to avoid swallowing the bitter pill of adjustment. This time, it was clear from the outset that action would have to be taken if the industry were to master the new situation.

The study provided a wealth of interesting insights and recommendations. The first big surprise - at least for outsiders - was the discovery that the industry was wasting considerable amounts each year through certain deficiencies in governance, management and production methods. The second theme of the study was the poor banana quality resulting from an inappropriate pricing system. In effect, price differences paid to farmers were not sufficient to reward extra attention to quality aspects.

The study's recommendations pertaining to management, production and quality were all agreed in a meeting on 29 September 1995, which brought together the Prime Ministers, the EC and other donors. Prime Minister Mitchell of St Vincent labelled this chance for the industry to get its business right as 'the last train to San Fernando'.

What has happened since then ? After some hesitation, the industry has indeed begun to 'take up arms against its sea of troubles' (to return to the Hamlet analogy). The EC, for its part, has taken the part of Horatio, the faithful friend. Its role is a delicate one though - for the EC has a lot of money available. Take, for example, the ECU 25m allocated to St Vincent in the 1994 STABEX exercise (roughly five times that country's national indicative programme). How are such funds to be injected reasonably into the islands without undermining their own strength and sense of purpose in pursuing the right strategy.

To answer this, one has to look at the actual requirements. Streamlining the banana industry is less a question of big infrastructure projects than of providing expertise to guide the necessary structural changes. It also means fewer people will be employed in the sector. Aid should, therefore, focus on technical assistance, promoting diversification, and social 'cushioning'.

The challenge, of course, remains considerable and the outcome will not be known for some time. But it is clear that the Windwards have taken bold steps in the right direction and that further steps are on the agenda. There is also little doubt that the islands small, sweet bananas can only be competitive in their market segment if they are produced and marketed professionally, and with dedication.

So what could Hamlet have learnt from this experience ? In short - get sound analysis and fresh advice from outside - and then boldly implement. And stick close to your good old friend, Horatio!

M.D.

The most recent meeting of the EC`s Development Council was one of the first to be hit by the non-cooperation policy adopted by the UK in protest at the export ban on British beef. The Overseas Development Minister, Linda Chalker, announced at the outset to her fellow ministers: 'I will not be able to agree today to the adoption of those texts... on which unanimity is required'. Britain is seeking agreement 'for a step-by-step lifting of the export ban', which was imposed after scientific evidence suggested a link between Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) - and its human 'equivalent', Creuzfeld Jakob Disease. Cases of BSE have been recorded across Europe, but the vast majority have been in the UK.

Texts which were approved included a regulation on refugees in non-Lomé developing countries. This makes available ECU 240 million over a four-year period (19961999) for longer term assistance to refugees and displaced persons - mainly in Asia and Latin America. Also agreed were two three-year programmes covering Aids control and environmental projects respectively. They will cover the period 1997-1999, and each has been allocated the sum of ECU 45m. In addition, ministers confirmed a regulation on the criteria for disbursing humanitarian aid.

But the British stance meant that a number of important resolutions were blocked, including a text on mounting projects which link emergency, rehabilitation and longer-term aid. Rino Serri, Italy's Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs who presided the Council meeting, said that once adopted, this approach would represent a 'qualitative leap for the EU's development policy.'

Other resolutions awaiting approval relate to the strengthening of coordination between Member States, evaluation of the environmental impact of development policies, decentralised cooperation, and migration and development. Since good headway was made on these subjects despite the British attitude, the texts are expected to be speedily agreed once the UK lifts its veto. Ministers also had an initial discussion on a paper presented by Commissioner Pinheiro on preventing conflicts in Africa.

As is customary at these biannual meetings, several delegations raised points of particular national concern. Belgium, for example, is worried about the Commission's proposal which would finally establish the single market in chocolate products while leaving Member States the choice of adapting their legislation to allow a vegetable oil content of up to 5% in chocolate. Belgium feels that this approach could ultimately prove harmful to cacoa-producing countries and claims that it will be difficult to control the exact percentage of oil used. Sweden, meanwhile, wants action to reform the UN institutions while Italy is keen to increase public awareness of development policies. Finland emphasised the need for better coordination between the European Community and its Member States on environmentally sustainable projects.

The Great Lakes region

There was backing for the June Round Table meeting on Rwanda organised by the UNDP, as well for the various diplomatic initiatives aimed at bringing stability to the Great Lakes region. On 27 May, the ministers dined with Emma Bonino, the European Commissioner responsible for humanitarian issues, and with former US President, Jimmy Carter, who has played a major role in the search to find a solution to the region's problems. Others active in this effort include South Africa's Archbishop Tutu, and former Presidents Nyerere and Touré of Tanzania and Mali respectively. Ministers also commended the efforts of the UN and the OAU.

Mr Serri said there was a 'desperate need for a ceasefire' in Burundi and called for a 'speeding up of the peace process and full deployment of available humanitarian and development aid.' He told journalists it was vital for the EU to make special efforts to strengthen the judicial systems in Rwanda and Burundi - 'so that the justice system can work properly and identify those responsible for the genocide.' He pledged that 'substantial resources' would be made available once peace is secured. Ministers also called for a control of arms sales to the region, although they have no power to legislate in this area, which remains the preserve of the Member States.

Outside the meeting place, Senegalese fishermen and NGOs joined forces to mount a protests against the effects of traditional EU fisheries agreements. These provide financial compensation to governments in exchange for access to their waters for EU vessels, but the protesters claim that they harm local fishing industries and disrupt food supplies. A significant number of agreements are due to come up for renewal later this year. NGOs are lobbying for a new and 'fairer' type of accord which provides for catch reductions, more selective fishing methods and the employment of locally-hired fishermen on EU boats. These proposals are all set out in a paper entitled 'The Fight for Fish: Towards Fair Fisheries Agreements,' published by Eurostep, a Brussels-based NGO.

D.P.

Cape Verde has been shaped by the harmattan, the hot dry wind which blows from Africa, strong ocean currents and five hundred years of Portuguese colonialisation. Portugal has been a constant presence in the archipelago's history since the fifteenth century, when it granted the colonists who were to settle on the islands of Cape Verde a monopoly over the slave trade. The country became an interface between Africa, Europe and the Americas, at the centre of the triangle of trade in slaves, hardware and gold. The intermingling of black populations of every origin who passed through the islands meant that the country was unable to present a united face against the colonialist culture. The colonists were therefore able to impose their own culture, with their fervent and proselytzing Catholicism becoming the principal ingredientin the mixture that is Cape Verde. Strong, scorching winds from the desert have shaped the islands' landscape and inhospitable ocean currents mean that approaches to the islands are difficult, their rocky cliff faces plunging into the sea.

The mythical Portuguese colonial oasis

Up to the eighteenth century, Cape Verde was no more than a commercial centre for Portugal, its population at the end of that century barely exceeding 50,000, to be halved by the great drought between 1773-75. Other periods of drought regularly decimated the population and the arrival of new colonists and slaves did not offset such losses or compensate for the massive exodus which began in the early nineteenth century with the arrival of American whalers in search of crew members for their ships. Seven hundred thousand Cape Verdians currently live abroad, half of these in the United States.

Only four hundred thousand have stayed in their own country.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a period which signalled a turning point in the country's history, the population still numbered no more than 150 000. At the time, major sea voyages were being undertaken and Cape Verde's geographical location was highly valued. Mindelo, on the island of São Vicente in the north of the archipelago, developed as a coal-and-watersupply port for English vessels plying the route between India and the Americas, and England helped construct this port. However, Portugal's policy towards Cape Verde was double-edged. On the one hand, the islands were regarded as a natural extension of the home country, but as a competitor in terms of port activities. This led to Mindelo's slow development, although the trade in skins, fishery produce, coffee and salt could have made it a thriving centre.

A

The mixing of races in Cape Verde has often been held up as, so-to-speak, 'humane colonisation', but this opinion is not corroborated by the under-developed state of the country at the time of independence and the fact that Portugal implemented food security measures to combat the ravages of catastrophic famines only when under pressure from public opinion, at the end of the first half of the twentieth century. The island's colonists had always used slave labour to produce food or fabrics which enabled them to purchase more slaves and it was only when the slave based economy began to decline, which resulted in the impoverishment of the colonists, that a major grouping of free Blacks and rebel or emancipated slaves came into being. That is when the intermixing of races began. Therefore, before the abolition of slavery (18641869-1878), the vast majority of the black population of the island was free; both unmarried and married colonists would generally emancipate their children born of a secret relationship with female slaves. The aristocracy and white upper-middle classes continued to live a cloistered, aloof life and did not mix with other races. A second factor which would suggest that Portuguese colonisation of Cape Verde was sympathetic in outlook is the reputation of this small country's intellectuals; although colonisation created only a small intellectual elite which was the product of a single institution, the Mindelo College, opened in 1917. In a quote by Michel Lesourd, Deirdre Meintel refers to this phenomenon as the mythical 'cultural oasis'.

A nation born of a middle class in tatters

Through its contradictions, it was this black, mulatto and 'petty white' middle class which was to forge the mixed-race culture and national identity, caught between its own privileges and its aspirations of aristocracy, between its rejection of African culture (they sought a 'lusotropical' culture) and the need to find allies amongst the lower classes who retained African cultural values. In order to acquire the wealth and attributes of power, this middle class was to take over the lands vacated by the decline of the slavebased economy and which were often much improved by the former slaves (renamed 'tenant farmers' without a major change in their living conditions) preventing a major economic upheaval which could have put an end to this iniquitous system. Their wholesale appropriation of land explains why, today, there is a very high proportion of landless farmers in Cape Verde, seasonal agricultural workers who survive only thanks to the State's welfare system.

This petty bourgeoisie was to give birth to growing awareness which would lead to calls for independence. Officially, Cape Verde was not a colony but a province, and its inhabitants in theory had the same rights or lack of rights as Portuguese citizens in Salazar's 'New State', where the right to vote depended on social and cultural status. In other Portuguese territories, members of the petty bourgeoisie held the rank of colonial administrators and, from their ranks, the pro-independence movements emerged. Such was the case of the PAIGC (Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde pro-lndependence Party), created by Amilcar Cabral, a symbolic figure in Africa's striuggles for independence and Cape Verde's national hero. He was assassinated in mysterious circumstances in Guinea-Conakry in 1973. His brother, Luiz Cabral, was to become president of Guinea-Bissau, and Aristides Pereira his successor as Party leader and Cape Verde's first president.

Cape Verde's uneventful transition to independence in July 1975 mirrored Portugalts Carnation Revolution and was quite unlike the fierce war entered into by Portugal in Mozambique and Angola. There was a clandestine struggle during which a number of combatants were imprisoned, but there was never any real guerilla warfare. The Portuguese governor remained at his post until he was replaced by an ambassador. The PAIGC was to govern both Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde until the coup d'état against Luiz Cabral in Guinea-Bissau in 1980, when it adopted the name of PAICV in Cape Verde, thereby signalling the end to any dream of a union between the two countries.

Diplomatic ventures

The new state pursued an even-handed diplomatic approach and accomplished the considerable diplomatic feat of remaining equidistant between the Cold wer's principal adversaries, adapting over time to all the changes which occurred on the world scene. Post-independence, embassies were opened by the United States, China and the Soviet Union. Cape Verde, with its marxist leanings, maintained the former links created with apartheid South Africa by Portugal. The arrival in power of a liberal party had no effect on this diplomatic tightrope-walking act. It was South Africa which was to provide aid to build the international airport at Sal. Ironically, after the establishment of democracy in South Africa, it was at this very airport that President Mandela was to stress his desire for strengthened links with the archipelago. Latterly, Cape Verde has demonstrated this flexible in its recent decision to Join the group of, French-speaking countries whilst still regarding itself as a mouthpiece for the Portuguese-speaking world, enjoying a privileged relationship with Portugal, the Azores, Brazil and African countries where the official language is Portuguese. It is also a very active member of the CEDAO (Community of West-African States) and its President is currently chairman of the CILSS (Inter national Commitee to Combat Drought). Cape Verde receives as much aid from China as from the US, from Russia and Sweden as from Cuba and Japan.

This diplomacy is in keeping with the atypical 'Marxist' Party which first initiated it. With its interventionist approach to economics, its highly developed social policy which gives priority to education, health and combating unemployment through public welfare, this party could be regarded as a socialist party, yet it opted decisively for a market economy. Its single-party structure mirrored the example of would-be popular democracies, but it never set up a system of repression and terror: only one opposition member's death is said to have taken place in suspicious circumstances on the island of Santo Antao. The population was able to discuss politics at popular assemblies and held no fear of openly criticising the government and, in the case of the well-off, of displaying its wealth. A mudança (change) was implemented calmly and collectedly by the PAICV when it was in power, sowing the seeds of its own downfall. With no pressure from street demonstrations and no insistent demands from political classes, the government of President Aristides Pereira and Prime Minister Pedro Pires adapted to the new situation created by the fall of the Berlin Wall. In early 1990, the PAICV gave up its privileged position as the single party and, one year later, at the legislative elections in January 1991 and presidential elections in February 1991, Africa witnessed the first democratic overthrow of a single-party government which had achieved independence. After the legislative elections, the PAICV, which had placed too great a reliance on being credited for its good governance, was silenced. The desire for change was too great and the position adopted by the Catholic church, anxious to punish a party which had dared to opt for a referendum on abortion, did the rest. President Aristides Pereira's personal prestige stood for little in the full face of this onslaught.

What change?

Prime Minister Carlos Veiga, who had founded the MPD only eight months before his overwhelming success in the 1991 elections, became the new figurehead in Cape Verde politics. His power sharing with Antonio Mascarenhas Monteiro was again successful at the most recent elections (December 1995 and January 1996). Shortly before the poll, the MPD experienced a near-fatal split, but the new party which emerged, the PCD, had only one representative as against 50 (an absolute majority) for the MPD and 21 for the PAICV, which continued to exist. Three other parties taking part in the elections fell by the wayside and the polarisation of Cape Verde's politics into two camps locks set to continue. This is the second time that the MPD has surprised its opponents - this time, the political adversaries had attacked the MPD's attempt to curry favour, but the majority of the electorate, concentrated on the island of Santiago, continued to show their appreciation of the visible signs of modernisation in their lives and also the government's seductive politics, particularly in the ran-up to the elections. The country had also had a good harvest and, although this was unconnected with the MPD, that party could only benefit from it.

Despite what MPD leaders might say, there has been no real ideological split, any political reorientation having been instigated in 1990 by the previous regime when it threw off its socialist trappings. Diplomacy remains pragmatic and the new government's liberal rhetoric and social policy, particularly in the areas of education and health, has essentially been maintained. Suspension of the State's collective works programme, the symbol of the State's interventionist social policy, is only temporary, according to statements issued by the Prime Minister, counter to several rumours.

More visible changes have taken place in the economy: partial liberalisation of the banking system; legislation relating to foreign investment; suspension of the requirement for preliminary import authorisation; despite the government's backtracking as regards certain basic products; privatisation of State assets, particularly in the hotel business, etc. Here, too, the PAICV government engineered the changes, but it can surely not be criticised for maintaining a delicate balance between the new demands of the global village and the social practices of a country which is very poor, but which is succeeding in putting an end to its poverty and creating a modest quality of life, but a secure one. Given its bleak geographical location, Cape Verde is simply continuing to make the best of history.

Hégel Goutier

The arrival in Praia on 30 April of a throng of IMF officials cannot have failed to cause the government some concern, despite its air of calm. Ministers repeated publicly that Cape Verde had already carried out its own programme of structural adjustments, that they were on the same wavelength as the Bretton Woods institutions, and that they could not, therefore, see any reason why any further adjustments should be imposed upon them. Nevertheless, the fact that the Cape Verde escudo has had rather a bumpy ride since last year's elections, trading sometimes by as much as 15% under its official rate on the parallel market, caused a certain degree of anxiety within financial circles, with the banks taking action by freezing certain credit facilities.

The government insists that this situation has by no means arisen because of a sudden anxiety raised by opposition parties as to the effects of possible devaluation The truth is that there is a genuine structural imbalance caused by the trade deficit, a disequilibrium which is only being partially offset by official development assistance and the transfer of currency by Cape Verde emigres. As a percentage of the GDP, the overall budgetary deficit has tripled between 1993 and 1994 (increasing from 3.3% to 13.6%). For a country which could always be relied upon to pay its debts promptly, Cape Verde is now, for the first time, in arrears with its payments (see the 1995 report of the Bank of Portugal). The servicing of external debts represents 25.7% of goods and services exported - although these are relatvely small compared with neighbouring countries - the country's total outstanding debt is now nearing $200 million.

Although Cape Verde is one of the LDCs (least developed countries) with a total GNP of approximately $850 per capita, out of a total of 174 States, it actually ranks 123 in the Human Development Indicator Tables, which take into account various factors such as life expectancy, education, etc. Its position near the middle of these tables clearly shows that, although the country is poor, its affairs are nevertheless being managed fairly efficiently. Boasting an adult literacy rate of 66% and a life expectancy of 64.7 years, Cape Verde is well ahead of those countries at the bottom of the list, which include a number of its Sahelian neighbours. Efficient administration of the State and the absence of rampant corruption are further feathers in the nation's cap. These achievements have earned Cape Verde much esteem from its sponsors, which goes to explain the prudence of the Bretton Woods institutions and their relative sympathies towards the country.

Unkind Mother Nature

Cape Verde's history has been punctuated by great famines. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries the country suffered no less than 30 famines, with this century seeing some of the cruellest: 16 000 people died in 1903-1904, the death toll in 1921 was 17000, in 1941-43 it was 25000 and between 1946-48 famine claimed 20 000 lives - a figure which at the time represented 20% of the total population of the archipelago. After the last famine, the colonial authorities, under pressure from international opinion, adopted food programmes which made the country more able to cope with the consequences of subsequent droughts. The last great famine ended 50 years ago. The nation may no longer be hungry, but the factors which make its inhabitants' lives so difficult remain. The main reason lies in the country's geography. Cape Verde has virtually no permanent springs and the topography of most of the islands, which are very mountainous, means that heavy rain simply runs down to the sea, the parched soil being unable to absorb it sufficiently. What is more, these downpours simultaneously wash away the little arable land that do" exist, thereby aggravating erosion. The whole situation is further worsened by the fact that the winter in this Sahelian region is very short. Despite huge efforts by successive governments, barely half the population has access to drinking water, with this figure barely reaching 25% in rural areas.

With a population of less than 400 000, there are just not enough people to pull off the miracle of making such an unforgiving soil bear fruit. Hence, although providing 50% of all jobs, agriculture represents only 17% of the nation's gross domestic product and produces only 10% of food consumed locally. The mountainous islands that make up Cape Verde are like teeth jutting out of the sea, and with virtually no continental shelf to speak of, small scale fishing is extremely difficult. Even with industrial equipment such as that installed on board large trawlers, catches are small - so small in fact that the country's fisheries agreement with the European Commission brings it only one million ECU over three years, one tenth of the proportional amount earned by neighbouring Senegal. Fishing thus represents less than 4% of the GDP.

Mere survival - a

Herculean task

Transport difficulties are another handicap for the economy. The sheer force of the harmattan, the strong ocean currents and the fog which often covers the region, make journeying by boat between the islands frequently hazardous. In addition, the volcanic relief of the islands makes them difficult to reach and means that there are very few locations that make suitable har bours. construction is both complex and costly due to the steep rocky barriers that seal off deep valleys. Those roads which have been built under the FAIMO scheme (Highly Labour-lntensive Projects) have sometimes turned into real labours of Hercules, and many areas, especially those on sparsely-populated islands, remain completely cut-off. The use of aeroplanes only partly solves the problem. Although competitive, the prices charged by the national airline, TAICV, are still too high for the average inhabitant.

Not only does the soil on Cape Verde contain very little water, it has virtually no natural resources: a few stones, lime, pozzolana and a little salt. Within the manufacturing sector (which makes up less than 20% of the GDP), only the construction and civil engineering industries, representing more than 10% of the GDP, contribute in any significant way to the economy, thanks partly to the transfer of currency from emigres who invest in the construction sector and works with wide public interest. These works, known as FAIMO schemes, have to some extent given this impoverished country a gloss that masks its poverty. Launched after Cape Verde gained its independence, they employ more than 25 000 people for up to ten months of the year in the construction of paved roads or in reafforestation projects, and ensure the survival of one hundred thousand people - over one quarter of the population. The workers are on the whole recruited from among farm labourers, with another large section of the workforce being made up of 'Solteiras' or 'single women', numerous in a country where the male population is constantly emigrating. Unfortunately, the liberal option adopted by the present government has cast some doubt as to whether these projects will continue and this year, for the first time, work ceased in April - three months ahead of the usual termination date. Yet the poor wages which these seasonal jobs pay (ECU 2 per day) are sometimes the only source of income for some families.

Only the tertiary sector shows a healthy balance of trade, accounting for more than 60% of the country's gross domestic production, with the biggest slice of the sector going to the hotel industry, followed by the transport industry. Although, overall, Cape Verde's balance of trade records a large deficit, the balance of trade for the services sector generally shows a profit, with the transport services provided by the international airport, Amilcar Cabral de Sal, alone accounting for 13% of exports.

Barely 10% of commercial goods are domestically produced and this has at times fallen below 5%. Cape Verde is therefore genuinely dependent upon foreign aid. Official development assistance represents 27.8% of the GNP (1989 figures), having risen from 17.7% to 27.2% of the GNP between 1980 and 1986. Cape Verde also relies on a second source of income - its emigrant population. In 1990 the currency transfers of its emigres represented nearly 20% of the GNP.

The colonial heritage

Contributing too to the country's poverty are relatively low educational standards. In this area too, successive governments have continued their predecessors' efforts to improve standards of education. However, at the time the country achieved independence, it was in a deplorable state. The reputation of a small intellectual elite of Cape Verdians had, over several decades, led the world to believe that Portuguese colonial rule had been 'enlightened'. This was a mere illusion. It was not until 1917, when the Mindelo grammar school was founded, that the country was able to claim an educational establishment of any cultural sophistication. The Mindelo school was the first state school in the country and it was to provide the nation with its first batch of 'home-grown' intellectuals. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, the Church, which was in charge of all matters educational, had provided basic primary education; then, at the end of the last century, it opened two secondary schools with the purpose of training students for positions in government and the civil service.

Even so, the Mindelo school remained an exception until the middle of this century. In 1950, no more than 5000 children received primary education and no more than 400 went to secondary school. Thirty years earlier, the figure was slightly higher, but Salazar, with his retrograde ideologies, saw education as dangerous and threatening and trimmed the number of schools on the islands from 150 to 60. True, Cape Verde was undoubtedly in a better state than other Portuguese colonies, but, with an illiteracy rate of 80% at the beginning of the 1960s, its position was nevertheless far from enviable. It was not until independence that any real progress was made, with 60% of children attending primary school in 1989 (the average for LDCs is 54%). However, this figure is still well below the average for developing countries, which stands at 90%, and even now, only 13 % of children have access to secondary education. As for higher education, this is virtually only available abroad; in Europe, Brazil, USA and Cuba, in particular.

Serious health problems still exist, exacerbated in particular by the scarcity of water. The cholera epidemic which has struck several African countries over the last two years has killed over 150 people in Cape Verde. The prevalence of AIDS exceeds the average for sub-Saharan Africa, with more than 2000 people being HIV positive and with some one hundred having developed the full-blown disease. According to official figures, 70 have died of the disease. The cholera epidemic which, unlike previous epidemics has affected towns much more than rural areas, is a sign of the deterioration of sanitary conditions in towns - particularly in Praia - affected by a lack of water, a dilapidated sewerage system and overcrowding.

Anchoring the country's economy in its culture