Africa - Caribbean - Pacific - European Union

Country reports

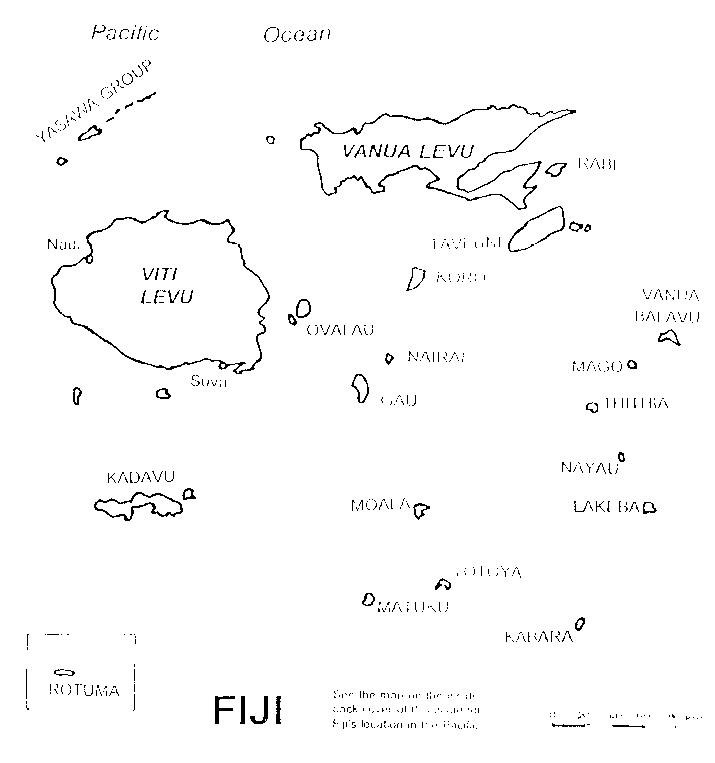

Fiji

Fiji is home to people of a variety of cultures but it would not be accurate to describe this Pacific island country as a 'melting pot'. Politics here are dominated by the difficult relationship between indigenous Fijians and the descendants of indentured Indian labourers brought in to work the sugar cane fields. We look at how this situation affects the economy - which everyone acknowledges has considerable potential, and examine the prospects for ethnic rapprochement as the nation begins a 'great debase' on the future shape of its Constitution.

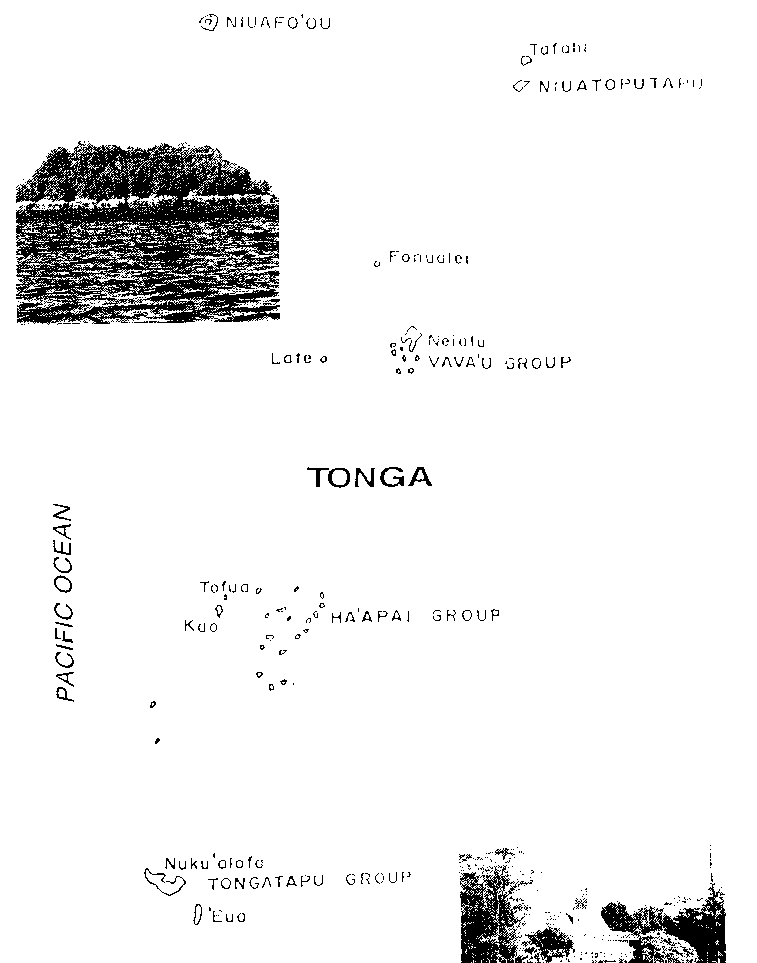

Tonga

Tonga appears like a haven of tranquility in a turbulent world. A society which respects hierarchies and is strongly attached to 'traditional values', it is also one of the few remaining places with a hereditary ruler who wields substantial power. But outside influences cannot be ignored altogether and nations everywhere are having to adapt to living in the 'global village'. Our report focuses on the possible consequences of this for the 'Friendly Islands' as the new millenium approaches.

Dossier

Habitat

The concept of 'habitat' conjures up different things to different people - from the right to a roof over one's head to the way in which we manage the flora and fauna of the planet. In our dossier, we consider the legacy of the United Nations 'Habitat' Conference held in Istanbul earlier this year. We also highlight some of the initiatives being taken to improve the quality of people's living environment.

The Courier: Africa - Caribbean - Pacific - European union

Address: Postal address (mail only) 'The ACP-EU Courier' Commission of the European Communities 200, rue de la Loi 1049 Brussels Belgium

The Courier office address (visitors) First floor Astrid Building 1, rue de Geneve Evere- Brussels Belgium

Publisher Steffen Smidt commission of the European communities 200, rue de la Loi 1049 - Brussels (Belgium) Tel. 00-32-2-299 1111

Director of Publications

Dominique David

Editor

Simon Homer

Assistant editors

Augustin Oyowe

Jeanne Remacle

Associate assistant editor

Hegel Goutier

Journalist:

Debra Percival

Production Manager:

Dorothy Morrissey

Secretariat:

Carmela Peters

Fax: 299-30-02

Circulation:

Margriet Mahy-van der Werf (299-30-1 2)

The main development battle must be fought in the towns and cities

Founded in 1972, Enda Tiers Monde ('Enda' stands for 'environment and development') is one of the few large international NGOs to be based in a developing country. It has a presence in a number of states in Africa, Latin America and Asia and has been concentrating its efforts on towns and cities, in the belief that this is where deprived populations can be best assisted. Jacques Bugnicourt, who is Enda's Executive Secretary, has some strong views about what needs to be done to tackle the problem of urban deprivation. When we interviewed him at the Enda headquarters in Dakar, Senegal, we began by asking him about the history of the organisation that he heads.

- When we launched Enda, I am not sure that we had any particular goal in mind. You would have to go back to the end of the 1950s, with the war in Indochina, the approaching conflict in Algeria, the independence of countries in Africa and the last-ditch struggles of the colonial powers, notably France. It was in Paris that links were forged between activists from many Third-World countries - in particular, we all took part in the street demonstrations mounted by people from the French colonies. There were some very strong groupings like the Federation of Students from Black Africa, and its equivalents set up by students from the Maghreb, Latin America and Asia. Ten years later, in the 1970s, we could see that the independence experiment was turning sour and the hopes we vested in the actions of determined and brilliant people had come to nothing. The United Nations was becoming increasingly bureaucratic. Some of our friends and colleagues who had government posts had their hands tied, while others were in prison and were equally powerless. In addition, the communists were disappointed at not being able to apply their doctrine to local conditions. Some did, in fact, manage to achieve small-scale results locally when working at the grass-roots, but by and large, their efforts were not successful. I came to Dakar, where I taught in a United Nations institute.

A lot of people had theories. But you cannot take up the battle for the poor without the poor themselves, or for those under the yoke of colonial rule without the participation of the subjugated population. To begin with, you have to appreciate the diversity of the various peoples in developing countries, and be aware of their daily life and struggle. Cesaire wrote that you had to ask questions about the soil, about cities, about men and about the sun. Later, once you have done this, you can act.

We need to dismantle the barriers. There can be no agronomy without economics, and no economics without sociology. If you are talking about jobs in Senegal, you also must talk about jobs in Mali and Guinea - treat Africa as a whole. Another thing is that you have to stand up for yourself and not allow yourself to be manipulated by people from the developed countries. One of the major problems we have noticed is that part of Africa's elite is out of touch with the general population.

These are the underlying reasons for the foundation of Enda. Nowadays, it is a non-profit-making international organisation working with various communities - an 'INGO', if you like, with the 'I' standing for 'international'. We have bases almost everywhere in the Third World, from Ho Chi Minh City to La Paz.

· Is each section of Enda independent, then ?

- Yes. We took the view that there was a danger of becoming too centralised and acting like a small-scale UNICEF or UNESCO, so we decided to guard our independence very carefully. We opted for the widest-ranging autonomy possible. This has its drawbacks of course, but these are far outweighed by the advantages.

· You mention drawbacks. Would it be true to say that the original enthusiasm which greeted the creation of Enda has fallen off somewhat ?

- That's something we are always concerned about. It is not structures which maintain cohesion, but the sharing of goals and the channelling of our actions towards the common good.

When the various sections get together, we find that we have a great many things in common. But there is no good reason why those of us in Dakar should try to influence the way people work in working-class districts in Santo Domingo, for example, where they are trying to tackle problems like AIDS and unemployment. We simply tell them what we are doing here and vice versa. If you want to serve the people, you have to have a decentralised set-up. It would be wrong to deal with a problem centrally, and to do so would be against our instincts. Most of us have no particular liking for institutions. An institution must be of service in the battle, not the other way round.

· How do you guarantee cohesion in practice ?

- It costs a great deal to travel of course, but we do have a lot of joint programmes. For example, the cities programme includes people from Bogota, Santo Domingo, Rabat, Dakar, Ho Chi Minh City and Bombay, all working together. They meet from time to time and, when they do, it is to get down to practical work. Together, their work is, say, three-quarters practical and one quarter reflective. Nevertheless, there is ongoing tension, particularly in the relationship between overall policy and local demands. Another conflict arises between grass-roots action and reflection.

· The impression one gets is that you yourself are the 'cement' between the various groups which make up Enda. Could this not be seen as a weakness which may make things difficult in the future ?

- That's what other people say, not what I think. I try to make my presence useful and those who come after me will do the same. What really holds us together is our belief in what we are doing. It is not a question of adhering to some kind of 'monolithic' faith. We simply believe that we can be of use, recognising that there are many limitations. Let me give you a practical example. If someone involved in recycling in Bogota were to meet up with someone from a poor district in Dakar who works at the rubbish tip, they would have a great deal in common and would find it useful to compare their problems and consider practical ways of solving them together.

· What are your most important activities in Senegal ?

- By far the most important is the one covering the city of Dakar. As well as being a focus for the country itself, Dakar is a metropolitan centre for the entire sub-region, with influence over Bamako, Conakry, Bissau and perhaps even Praia in Cape Verde and Nouakchott in Mauritania. What happens here has repercussions in all those cities. I do not want to sound too dramatic, but the decisive factor in our destiny will be the fate of young people and the poor in the major cities. Two-thirds of these people are facing chronic problems. Those under twenty make up more than half the population and their lives are continuing to spiral down into poverty.

Enda should obviously be operating in those areas where it can be of most use. And in the context of towns and cities, we have completely reviewed our strategy. For some years we gave priority to the countryside. For a long time, in fact, we believed that rural development would permit a much improved urbanisation process. There was even the view that people in developed countries would not object to paying a little more for agricultural produce, because they could be certain that the money was going to those who actually grew the cotton, groundnuts, cocoa or whatever.

Over the last fifteen years or so, though, we have come round to the view that our actions must be directed principally at towns and cities. We found initially that there were some interesting projects involving small groups - working to improve the position of children or banding together in cooperative savings ventures. It was good, long-term work which gave results. But that is all out of date now. We have to speak in terms of much larger numbers - tens of thousands and not tens or hundreds. Otherwise, there is no chance of making a real difference. That is why we have considerably altered our strategy. Three years ago, approximately two thousand children were able to go to holiday camps. Most of these holidays were paid for by companies, but fewer than 10% of the beneficiaries were genuinely poor. Last year, no fewer than 10 000 children were sent away on five days' holiday - to the coast near Dakar. Enda was involved in this programme working with 200 local cultural and sports associations. The idea was to give the children the chance to splash about in the sea, but also to use African resources to help them become full citizens and learn that our diversity is the source of our wealth. There are at least 100 000 children living in misery and many of them could end up joining the ranks of the street children. If you can give these youngsters five days holiday plus a bit of follow-up, you allow friendships to be built. It offers a brief escape from everyday reality. It may not be paradise, but it is something tangible.

Another example is the tontines that have been formed into a federation. We currently have nineteen thousand women participating in these and if you bear the large family sizes in mind - there are perhaps ten people in every family - that represents a lot of people. The women pay into the tontines and the money is used, not just for the security of their immediate family, but also to help young people set themselves up.

Then there is rubbish collection. Enda runs its own scheme but there are also a number of groups that have turned rubbish collection into a profession. The young people collect the rubbish and recycle it. There are about 50 000 people in the biggest district where we are involved in rubbish collection. There are also some young people in that district who are engaged in water recycling and although it only involves supplying about a hundred people at the moment, I believe this scheme will grow.

We also organise schools and are currently involved in making films for schools on the subjects of the environment, hygiene and solidarity.

· Enda has just opened an 'eco-centre'. If I understand it correctly, this is a showcase to promote a horizontal link between Enda's various activities.

- That is right. We want it to be a place of passage, meeting, exhibition, permeation and redistribution. We hope people will feel comfortable there, and that it will be a tool symbolising a new way of working. So the centre offers an experience, but we also want it to be used to promote activity. A variety of events have been organised there simultaneously - recently for example, a meeting of shoe-shiners, a gathering of teachers from a long-standing educational centre, an exhibition for the Biennial Festival of Contemporary African Art, and a local-community meeting about setting up a small production facility. Two days earlier, there was a preliminary holiday-camp meeting where the instructors got together to look at the best available teaching methods designed to make children more aware of the importance of solidarity. We believe that solidarity is essential in tackling problems.

So the centre has a multitude of uses, all of which contribute to the vitality of the local economy. You have to understand the crucial importance of the local economy. It responds to all the basic needs of the poorest people, who want to live their lives just like the rest of us.

· You talk of depending on the local (what some would call the informal) economy to live - or at least survive. But this sector is not viewed with enthusiasm by the international authorities ?

- Their policy is based on domination and fear: fear of those who accumulate assets. To see these hordes of people in the developing countries frightens them. It's a bit like the horror of the wealthy classes at the end of the nineteenth century when faced with a working class which dared to aspire to wealth. They will give to charity but are not prepared to make a long-term investment. The lack of support for the local economy stems from the fact that foreign aid is geared, first and foremost, towards major projects or emergency aid. Four or five years ago, the UN conducted a survey in 10 towns and cities in West Africa, but the results were not published because they showed that the average rate of growth of the local economy was 7.5%. So, you see, we are far from just muddling along. Great things could be achieved if only there were a change in attitude. It also requires a change of terminology. How can one justify the use of the word 'informal' and, worse still, treat the work of the poorest people and fraudulent activities under the same heading. Fraud may be formal or informal. Knowing African society as I do, I am aware that fraud is statistically more widespread amongst the prosperous and highly respected. So we must not cast stones at the little man selling socks who has no trading licence because he cannot afford one, or at the woman who sets up a stall at a school entrance without complying with the law which requires a recent certificate stating that she does not have tuberculosis. What is the bottom line here ? Must we respect the law or the people who want to live without being thieves, beggars or prostitutes ? It is unacceptable for force to lie with the law and for the majority to be cast into wretchedness.

In Senegal, there used to be fixed prices for milk. The World Bank protested, declaring that this was a restriction on free competition. Now we have to pay much more and many people can no longer afford to give their children-milk every day.

To put it in perspective, Senegal's economy is about the same size as that of the city of Bordeaux. So we must use all the available potential. Highly qualified managers should do their job looking after the high-tech sectors. But, at the same time, we should not be driving out the poor people who are just trying to eke out a living. The informal sector creates services for a very small investment, and people also require services. Economic policy must allow society to walk on two legs, not just one. What that means is that we need a great deal of flexibility, and perhaps a complete review of the law. Contraceptive implants have to be licensed so that there are no more back-street abortions. And it must be possible for girls to attend school even if they do not have a proper birth certificate - why should they be excluded from education for want of a piece of paper. It should be possible to trade with a simple one-day ticket which people should be able to buy in post offices or cinemas. What would be wrong with that? And we should have a moratorium on a number of regulations. We need to wage war on the destitution that we are suffering and that means taking decisive measure.

Although the agenda was, as usual, heavily laden with a variety of long-standing issues ranging from regional cooperation, fisheries, the cocoa content of chocolate and bananas to the situation in several ACP states (in particular Rwanda and Burundi), the future of ACP-EU relations was at the forefront of discussions at the ACP-EU Joint Assembly, which was held in Luxembourg from 23-26 September 1996.

Opened in the presence of the Grand Duke and Grand Duchess of Luxembourg, the Assembly's general attitude was not one of speculation as to whether or not the European Union would abandon the ACP states when the Lomé IV Convention expires in the year 2000 - a feeling that was rife shortly after the signing of the revised version in Mauritius in November 1995. Instead, it was one of positive thinking and of exploring the kind of agreement that would succeed it. 'There is no question of the European Union getting out of a relationship which took decades to build', Luxembourg's Prime Minister Jean-Claude Junker, told participants in his welcoming address.

As pessimism gives way to guarded optimism, ACP-EU parliamentarians have taken an important initiative, even before the Commission's Green Paper is published, in what is bound to be a long and passionate debate. A special summit of ACP Heads of State is planned for Gabon later in 1997 to discuss the issue.

Options for the future

A general report, introduced by Mr Firmin Jean-Louis (Haiti), provided the main platform for the Joint Assembly's deliberation. Although presented too late for representatives to have the opportunity to examine it in detail, the exchange of views on the floor was wide-ranging and reflected the report's content to a considerable degree.

The report encapsulates all the ideas that have emerged so far in various fore. It analyses framework options for future ACP-EU relations - bilateral, regional and multilateral - and raises pertinent questions and concerns. Noting that international cooperation is increasingly dictated by economic and security considerations, and that North-South solidarity is, as a result, being pushed to the background, it regrets the fact that certain EU member states appear to indicate a preference for bilateral over multilateral cooperation. The author of the report warns that this trend would not only diminish the credibility of the Union but also its international influence.

Any instrument of cooperation, the report says, should take into account the different levels of development among ACP states as well as the regional vocation of many others. Its objective must be poverty eradication, sustainable economic and social development, and the harmonious integration of the ACP states into the global economy.

It recognises the need to secure the support of European public opinion which is largely unconvinced that EU aid to ACP states has been effective over the past 20 years. Not enough publicity; it says, has been given to its positive aspects. The report goes on to warn that solidarity and development are at stake and that the debate on the future of ACP-EU relations should not be left to politicians and technocrats. It should also involve wider civil society.

In the Joint Assembly debate, the commitment of EU political leaders to the development of the ACP states was often called into question. Francis Wurtz (EUL-F) summed it up when he said there were worrying signs that the EU intends to downgrade its relationship with the ACP states - signs which go back to the negotiations on the Lomé IV second financial protocol, when several countries refused to increase their contributions to the 8th EDF. The EU draft budget for 1997, which he said revealed a substantial reduction in the funds allocated to the developing countries outside the Mediterranean region, provided further evidence of this. 'We must be vigilant,' he told his colleagues, 'and must not allow the Lomé Convention to be revised downwards.' Mr Wurtz agreed that greater efforts were needed to create awareness and mobilise European opinion in favour of development. The European public should know that EU development policy was not based on charity but on self-interest. 'Without Africa developing, Europe has little chance of maintaining growth in the long run.'

Lord Plumb (EPP-UK), the European Co-President of the Joint Assembly, admitted that it would not be easy to influence European public opinion. 'One of the roles of the Joint Assemby,' he said, however, 'must be to ensure that the peoples of Europe have confidence in the progress being made by the countries of the South. We must all help in this task of confidence-building.'

Glenys Kinnock (PES-UK) urged that there should be as much participation as possible in the ongoing dialogue over future ACP-EU relations in order to bridge what she saw as 'the gap between rhetoric and reality.' Equity, she argued, should be the main objective.

ACP Co-President, Sir John Kaputin (Papua New Guinea), said there was no doubt that the EU was forging closer ties with the former Eastern bloc countries at the expense of the ACPs. He pointed out, however, that the Lomé Convention had always encouraged a 'forward-looking' approach and argued that whatever succeeded the current ACP-EU relationship should be 'the most important' agreement ever.

The representative from Barbados, Dr Richard Cheltenham, was of the opinion that whatever the outcome of the discussions, efforts were needed to avoid 'chaos'. There should, for example, be no immediate abandonment of the trade preferences that ACP states had acquired. Transformation must be gradual to enable them to adjust and restructure.

European Commissioner, Professor Pinheiro, chose, first of all, to underline the importance of the role of 'the state and civil society' in development. He indicated that he saw this as growing more and more in importance. This was reflected in the agreement signed in Mauritius - an agreement which seeks to encourage the consolidation of democracy, the rule of law, good governance and transparency, and which emphasises decentralised cooperation and the role of the private sector. the Commissioner spoke about the current programming exercise, reminding the Assembly that resources were being allocated in two tranches in accordance with the provisions of the revised Convention, to take account of each ACP state's development strategy and the objectives and priorities of the Community's development policy. He revealed that only 16 ACP countries and two EU Member States had ratified the revised Convention and urged those that have not done so to accelerate the process.

He welcomed the Joint Assembly's initiative in debating future ACP-EU relations. The Commission's Green Paper, he told representatives, will be published in November. He was, therefore, not in a position to enter into detailed discussions with members on the subject at this stage. He stressed, nonetheless, that the document 'will not be a blueprint for future EU strategy towards the ACP countries. It will be a discussion paper.' there were a number of key questions that needed to be addressed regarding strategy, the scope of future relations and the use of the traditional instruments of aid and trade. 'This is not to say that we should start afresh', he argued. 'We should build on what has been achieved so far, and adapt where necessary.' Professor Pinheiro was certain that whatever the outcome of the discussions, there were a number of 'unchallengeable principles' on which ACP-EU relations should continue to be based. These were: partnership, ownership by ACP countries of their development policies, security in terms of EU support and predictability of relations.

New areas of concern

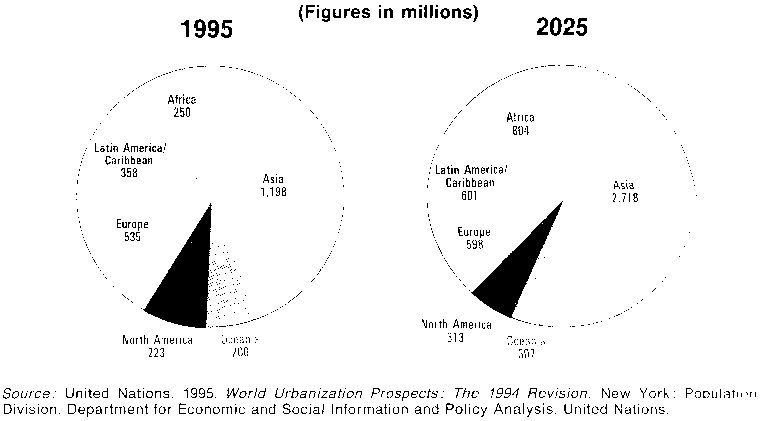

This session of the Joint Assembly saw the emergence of two new areas of concern: urban development, and the effects of climate change on small island states. An initial report on the former was presented by the rapporteur, Daby Diagne (Senegal). It did not give rise to much debate. The report emphasises the pivotal role towns play in economic development and urges the Community to adopt an integrated policy on urban development (See our interview with Mr Daigne in the Dossier). The latter was the subject of a full morning hearing, involving a panel of ACP-EU experts who are closely involved with the problem. They warned of the threat posed by global warming to the survival, and even existence, of many islands in the Caribbean and the Pacific. The emission of greenhouse gases, the Assembly was told, has reached levels never before experienced (see the article which follows). Representatives agreed on the need to integrate climate change considerations into sustainable development strategies. A Working Group on the issue was set up with Karin Junker (PES-G) as general rapporteur.

Cocoa and babanas

There was no avoiding the intractable problems of cocoa and bananas. On cocoa, opinions were divided as usual. There were those who felt that the Commission's proposed new directive allowing chocolate to contain vegetable oils (up to 5% of total volume) in place of cocoa butter, was reasonable. The proposal also involves a labelling system to ensure that the exact contents of the product are clearly indicated Advocates of this strategy argued that it would not only widen consumer choice but would also promote the export of shea-butter and other vegetable oils which a number of ACP countries produce. Opponents were worried that if implemented, the directive could lead to a big fall in cocoa exports and a commensurate loss of earnings for ACP cocoa producers. Magda Aelvoet (Greens-B) argued in favour of maintaining the status quo, saying that this was preferable to what was being put forward in the draft directive. She warned that the Commission propose' would almost certainly result in everyone (cocoa producers, shea-butter producers and consumers) losing out. There was no guarantee that menu facturers would choose shea-butter given that they would be free to use whatever vegetable oils they liked She was certain they would go for the cheapest substitute or even for synthetic products. Accordingly, Mrs Aelvoet proposed a 'freeze' on all proposals. This view was reflected in the resolution passed by the Assembly, which called on the Council to reject the proposed directive. It also requested the sever member countries which currently authorise the use of vegetable oil to comply gradually with the existing directive - which bans their use altogether.

The banana issue proved even thornier. There is a dispute at the World Trade Organisation, where the Lomé Protocol is being challenged by the United States and Latin American banana producers. Mrs Kinnock expressed anger at the fact that the arbitration panel set up by the WTO is made UP of three countries known to advocate free trade. The panel, she said, is chaired by Hong Kong - which the Organisation told her was representing the 'developing countries!' The general feeling among representatives was that the odds were stacked against the European Union and the ACPs. The Assembly passed a resolution asking the Union to stand firm in defence of the banana regime.

Democracy, human rights, peace and security

Twenty-seven questions were addressed to the Council of Ministers and a further 28 to the Commission. More than a third of these dealt with issues relating to emergency relief operations, democracy, human rights, peace and security - recurring themes throughout the four-day meeting. The emphasis, in this context, was on Burundi, Rwanda, Liberia and Nigeria, all of which were considered individually under the agenda item 'the situation in ACP states'.

In addition to the detailed answers given by Commissioner Pinheiro to questions on Burundi and Rwanda, the Assembly had a long session with Aldo Ajello, the EU's Special Representative to the Great Lakes. The discussion focused on efforts to restore democracy and legitimate government in Burundi, national reconciliation, and the repatriation of refugees from neighbouring countries to both Burundi and Rwanda. Mr Ajello gave members a comprehensive picture of the complex political and humanitarian situation in the region. He spoke of the sanctions imposed on Burundi by neighbouring countries and the efforts of the former Tanzania President, Julius Nyerere, to bring about dialogue and a just political settlement in Burundi.

Nigeria was again in the dock. Its representative, Dada Olisa, acting Charge d'affaires at the Embassy in Brussels, gave an account of what he considered was the progress made by the Abacha regime on human rights and democracy since the Joint Assembly met in Windhoek last March. He mentioned the repeal of the decree under which Ken Saro-Wiwa and other minority activists were executed, the release of detainees and the transitional programme for a return to democracy by 1998. He pleaded for the Assembly's understanding.

His explanation cut no ice with any of the seven political groupings in the European Parliament, who came together to present a compromise draft resolution on Nigeria. They wish to see all political prisoners released immediately, and the restoration of civil and political rights, as well as a democratically elected civilian government, by the end of 1996.

The resolution on Nigeria was again passed by secret ballot - the very last act of the session. It calls, among other things, for a total arms embargo (preventing the trade in future but also covering existing supply agreements) and for the financial assets of the Nigerian government and of members of the country's ruling councils (and of their families), to be frozen.

The resolution does not differ very much from the previous one. Mrs Junker, Johanna Maij-Weggen (EPP-NL) and Mrs Kinnock all expressed disappointment that the EU Council had failed to implement this fully. However, by repeating the demand for sanctions, they said, the Assembly was sending a very strong message to the Council that it was determined to see Nigeria return to democracy as quickly as possible.

Climate change

A morning session of the ACP-EU Joint Assembly was devoted to a public hearing on the effects of climate change on small island states. It was appropriate that the issue should be brought to the attention of the Assembly by Maartje van Putten (PESNL). Representing a country much of which lies below sea-level. she is familiar with the devastating effects of sea flooding. At the hearing, which was very well attended, a panel of invited ACP-EU experts was on hand to enlighten the audience on the extent of the problem.

Although global warning has been on the international agenda for more than 10 years, the seriousness of the threat it poses to the survival of small island states is only now beginning to be taken seriously - and it might already be too late, if some of the most apocalyptic scientific predictions are to be believed.

There is now growing evidence that global warming is taking place. In recent years, we have experienced more extreme weather conditions - heatwaves, floods and increasingly destructive tropical storms - while there are signs that icecaps are melting and sea levels rising. The increasing incidence of malaria in Africa has been linked to these changes. And it is all happening because of the influence our style of living is having on the planet - in particular the huge emissions of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane, from our factories, vehicles and so on.

That the public hearing attracted a large audience was not only a reflection of the interest the problem is now commanding. It also symbolised the mounting international pressure for reductions in CO2 levels in the atmosphere, and for the adoption of more realistic strategies of sustainable development.

The panel of experts comprised Dr Leonard Nurse, Manager of the Coastal Conservation Project in Barbados, Donald Stewart, Acting Director of the South Pacific Regional Environmental Programme (SPREP), Dr Robert Watson, Senior Scientific Adviser at the Environment Department of the World Bank and Chairman of the second Working Group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and Neroni Slade, Vice-Chairman of the Association of Small Island States (AOSIS) and AOSIS Coordinator on Climate Change. A separate workshop on climate change was also organised on the same afternoon outside the formal Joint Assembly setting.

According to Dr Nurse, current estimates based on most reliable models, suggest sea level is rising at the rate of 5mm a year (the 'range of uncertainty' is between 2mm and 9mm). This is two to five times the rate experienced in the last 100 years. This rise is expected to continue beyond the year 2100 even if greenhouse gases are stabilised. The implications for small island states, particularly the low-lying ones, would be severe. 'Atolls such as Tokelau, Marshall Islands, Tuvalu and the Maldives could possibly disappear', he said. 'Major population displacement would be experienced in Micronesia, Palau, Nauru, French Polynesia, the Cook Islands and Tonga.' Meanwhile, small islands with extensive coastal plains and limited upland areas such as Barbados, the Bahamas and Antigua, 'would be highly vulnerable to social and economic disruptions', as major cities, ports and tourist facilities, industries, freshwater sources, fertile agricultural lands and even coral reefs are destroyed by typhoons and cyclones, or washed away in floods. 'Given the limitations of climate models,' Dr Nurse said, 'it is not possible to state with certainty at this stage whether there will be a change in the behaviour of tropical storms and hurricanes. However, it is highly probable that an increase in the frequency and intensity of these phenomena could occur in a 'warmer world'. One study, he claims, predicts tropical storms would have a potential destructive force at least twice what they have today.

Dr Watson, similarly, struck a pessimistic note when he said that the potential for irreversible damage was great. He agreed with Dr Nurse that even if we took measures now to reduce CO2 emissions, stabilisation of the situation will take centuries. He pleaded for climate change to be taken into consideration 'in our everyday decisions.' Governments must not wait for cause and effect to be established before taking action. 'It is,' he said, 'economically feasible to reduce CO2' by introducing appropriate policy measures: looking at supply of and demand for energy, resorting to new and renewable energy sources, nuclear power, etc. and ensuring more efficient land management.

The question of 'burden-sharing' in the reduction of emissions between the industrialised world and the developing countries was debated at length. It was noted, for example, that small islands states are responsible for a very small proportion of the emissions, yet they bear the brunt of the consequences. There was a general consensus that burden-sharing should be based on equity and justice.

It should be noted that the Alliance of Small Island States (which was formed during the Second World Climate Conference in 1990) has called on the industrialised world to achieve a 20% reduction in their greenhouse gas emissions by the year 2005 (The 'Toronto objective'). This, it hopes, would bring CO2 in the atmosphere down to 1990 levels. Whether this is realistic is debatable.

However, a number of strategy options are being closely examined by the European Commision and the Council with a view to adopting Community-wide measures to reduce emissions significantly by 2005-2010. Member States have made phasing-out proposals with targets of 5-10% by 2005, 15-20% by 2020 and 50% by 2030. This works out at an average reduction of 196 2% annually from the year 2000.

Several parliamentarians wanted to know what the Commission, in particular, had done and will do to help small ACP island states overcome the effects of climate change. It was soon discovered during the discussion that a number of African countries were equally concerned. A Commission representative referred the Assembly to the provisions in the Convention which covered global warming and the special problems of island states. Although there is no specific reference to climate change, the Commission had dealt and would continue to deal with the issue in the broader context of its environmental action. Studies, projects and programmes are being implemented in the Caribbean and Indian Ocean in particular. Furthermore, DG VIII has drawn up internal briefing papers aimed at making departments aware of the issues of climate change and the environment.

In most of the ACP states featured in our Country Reports, the vital issues are usually economic and social ones. How is a nation with a poor natural resource base to achieve lasting development ? What can be done to improve the skills of the people? How can a vibrant private sector be created ? Can better health care be delivered and how should it be paid for? Some of these questions might well be valid for Fiji but the visiting journalist soon discovers that they are all secondary issues. For this is a country whose political system itself dominates the agenda. The fundamental issue here is the relationship between the indigenous people of Fiji and the descendants of indentured Indian labourers brought in by the British between 1879 and 1916 to work in the sugar cane fields.

Fiji, in fact, is home to people of a variety of cultures. On the indigenous side, the majority are Melanesians but there are also some Polynesians (living on the island of Rotuma). The country even plays host to Banabans, from Kiribati, who were displaced from their homes on Ocean Island to make way for the phosphate diggers. They hold a freehold to the island of Rabi and enjoy a special self-governing status. And while the Indians form the bulk of the non-indigenous population, there are also small Chinese and European communities as well as a number of inhabitants of mixed race.

Despite this diversity, it would be inappropriate to describe Fiji as a melting pot. Ever since the rapid expansion of the Indian population, official policy has tended to accentuate the divisions. In the early days, it was the British who were responsible for this, although one has to be careful to avoid value judgments. The colonial administrators, it seems, were aware of the tensions that would arise by bringing in large numbers of people of a different culture, language and religion. Their eventual response was to provide guarantees for the local population, notably as regards land rights. The effect was to preserve the traditional land tenure system which was based on villages and families. At the time, it seemed a logical thing to do, but several generations on, the country now has a settled population of Indian origin (43% of the total) who have limited opportunities to own land - even though many of them work on it.

As the economy has developed, each of the two main communities has found itself 'specialising' in different fields. For example, cane farmers and retailers tend to be of Indian origin while the public service has traditionally attracted more native Fijians. Significantly, the army is almost exclusively filled by indigenous people - a crucial factor in the 1987 military coup.

On the political front, as Fiji moved towards independence, the idea of providing separate representation for each ethnic group also took hold. The independence constitution of 1970 reflected this with the two main communities being given parity (22 seats each) in the House of Representatives.

Shattered illusion

Although there was no real assimilation between 1970 and 1987, Fiji was seen by many as a model of a successful multiracial society. It was only when the country got its first Indian-dominated administration (sustained in power by a smaller native Fijian party) that this illusion was shattered. There was a military coup led by Lieutenant-Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka, who is now the elected Prime Minister,. Shortly thereafter, Fiji became a republic (Queen Elizabeth was formerly Head of State) and in 1990, a new Constitution was adopted giving political primacy to the indigenous Fijians. Needless to say, it was a time of greatly heightened communal tension.

The 1987 coup and the events that followed have been well covered elsewhere (including our previous Country Report which was published in 1991). It suffices to say here that while the last few years have been a lot less turbulent, tensions remain. In 1997, the country must adopt a new set of constitutional proposals and a big debate is currently under way about the shape of the system of government for the 21st century. This subject is covered in a later article and also features prominently in our interviews with the Prime Minister and Opposition Leader.

The main focus of this article is therefore on economic and social aspects although, as one soon discovers, this frequently leads us back to the ethnic question. This is particularly the case when one considers the overall economic performance of the country. Fiji is not poor by developing nation standards and it has enjoyed modest growth during 1995 and 1996, but there is a widespread view that it could be doing a great deal better were it not for the political uncertainties. The problem is summed up by the Economic Intelligence Unit in its Fiji Country Report for the first quarter of 1996: 'Political instability will continue to deter investment, other than that on highly favourable tax terms.' In other words, Fiji is paying a high economic price for its internal difficulties.

General unease about the future and, in particular, the outcome of the constitutional review process is compounded by specific concerns over land tenure. The long-term leases granted to (mainly Indian) farmers are approaching their end and the government must soon decide what it should do next. Will any of the sugar cane farmers be evicted and if so, how many ? What alternative arrangements will be made for them? These questions remained to be answered when The Courier visited Fiji in July although, as our keynote interviews show, the subject was clearly exercising the minds of the politicians.

A long-term strategy for agriculture?

The way in which the land question is dealt with will have a crucial impact on the sugar industry - still the country's most important product in terms of its contribution to GDP and the jobs that it generates (see the article entitled 'Sugar definitely has a future'). With other uncertainties facing this sector - in particular, the process of global liberalisation - there is a growing recognition of the need for a long-term strategy. The government has a two-pronged approach - improving efficiency within the sector and diversifying into other agricultural products. To learn more about this, we spoke to Luke Ratuvuki, who is the Permanent Secretary for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forests.

Mr Ratuvuki began by stressing the scope for increasing the sugar yield per hectare by as much as 75% (and by even more with irrigation). If productivity could be boosted on this scale, Fiji sugar would be in a much better position to compete in open world markets. He admitted, however, that the country would still face a struggle in maintaining market share and, looking ahead ten years, foresaw a slimmed down industry providing high quality sugar with more of a focus on niche markets. This inevitably meant looking at other agricultural products as possible long-term substitutes. The coconut (or as the Permanent Secretary dubbed it, 'the tree of life') is traditionally grown here and seems poised to enjoy a new lease of life following a period of decline. Fiji has also picked up the taro trade at the expense of Western Samoa, which is affected by taro blight, while there are significant exports of ginger to Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Europe. Mr Ratuvuki spoke enthusiastically about branching out into other areas such as pawpaws, mangoes, bananas and aubergines.

Fiji has potential for growth in a range of non-agricultural sectors, but farming is sure to play a vital part in the economy for many years to come. Currently, sugar represents almost three quarters of all crops by value (excluding subsistence growing) and the Fijians are only too aware that this makes the country particularly vulnerable to external shocks.

The other primary sectors are all present in Fiji, albeit on a more modest scale. There is some deep-sea fishing backed by Asian investors. This provides useful employment although perhaps not the best possible financial return to the country. As one would expect in a nation of three hundred islands, there is also extensive artisanal and subsistence fishing in the inshore areas.

The forestry sector divides into two parts: artificial softwood plantations which are said to be managed sustainably and the naturally growing hardwoods. As regards the latter, the EU is helping with a mapping project. Although Asian loggers do not operate in Fiji, there is considerable land clearance taking place, leading to problems of erosion and silting.

Prospects for mining

Gold is the main mineral being exploited with important deposits around Vatukoula. The sector has had its ups and downs but the Emperor Gold Mining Company has now embarked on an expansion project aimed at raising production from the current level of about 4000 kilos per annum to 6000 kilos by the year 2000. A huge copper and gold mine is also planned for Namosi, some 35 km from Suva. Other minerals discovered but not exploited include bauxite, iron, lead, zinc, phosphates and marble. Mining currently makes a modest contribution to overall GDP but represents an important component in the export earnings figures.

With one key exception, manufacturing is on a fairly small scale with an emphasis on staple items (butter, beer, soft drinks, paint, soap etc.) for the local market. The exception is the garment industry which provides some 20% of the country's export income and a considerable amount of employment.

The investments in garment manufacturing and mining have been important in jobs terms and in improving the trade figures, but there are those who criticise the fact that the government appears to derive little revenue from the operations. The exact fiscal benefits are not easy to determine, prompting some observers to suggest that official secrecy should be eased (see the article on the Constitutional Review later in this Country Report).

In the service sector, long-term growth is foreseen in the key area of tourism. The number of holidaymakers choosing Fiji dipped sharply at the time of the coup, illustrating the importance of political stability in attracting visitors. Tourist arrivals bounced back once Fiji's internal difficulties had receded from the international headlines. The politicians must be hoping that nothing will occur during the current period of constitutional discussion and negotiation to put Fiji back on the front pages. It is worth mentioning here that Fiji's national carrier, Air Pacific, is an example of a relatively rare bird - an airline that makes money ! According to journalist Avin Rahish, writing in the July 1996 issue of The Review (the news and business magazine of Fiji): 'It is one of the few government investments that is profitable on its own.'

If tourism is a success story, there is something of a shadow over the financial services sector, which is more extensive here than in most developing countries. The reason is the collapse last year of the National Bank of Fiji with losses of US$ 142m (equivalent to 10% of the annual GDP). The authorities were accused of a failure in supervision and the taxpayers have had to pick up some of the bill. More serious, however, is the undermining of confidence in the system and it will take time for this to be restored.

Social challenges

As a middle-income country, Fiji has relatively favourable social indicators in the areas of health and education. Medical facilities are provided by the government but it is said that the public health system is not as good as it once was. This is attributed, among other things, to the emigration of highly qualified staff in the aftermath of the events of 1987. Nonetheless, the country does have 27 hospitals and one doctor for approximately every 1900 people. At 72 years, life expectancy is high compared to the ACP average.

The education sector is well-developed with more than 800 primary and secondary schools (for a population of less than 800 000) and 41 technical or vocational institutions. As a result, primary school enrolment is close to 100% while the 1986 census revealed that 60% of 15-year olds were still in education. On the other hand, there are concerns over the proportion of teachers lacking qualifications, notably in the primary school system. In practice, there is considerable racial segregation at both primary and secondary levels, although there is no official policy to this effect.

Educationally, the jewel in the crown is almost certainly the University of the South Pacific whose main campus is in Suva. This regional institution, which has departments in a number of other countries of the South Pacific, draws students from various island nations. Dr Vijay Naidu, who is the USP's Pro-Vice Chancellor, outlined some of the special features of this unique university which has to cater for a highly dispersed population. Like traditional tertiary institutions, it provides a wide range of degree programmes on campus, catering for 3500 students. It has a further 9000 who are being educated using the 'distance mode'. Distance learning is organised through centres in each of the participating countries. Students can attend these centres from time to time but much of their work is done through radio and telephone linkages and, increasingly nowadays, by e-mail and satellite communications. The University, Dr Naidu stressed, also provides continuing education at non-degree level 'in everything from computing to basket-weaving'.

Like the health sector, the USP suffered a loss of highly qualified staff after 1987 - and not just among employees of Indian origin. As the Pro-Vice Chancellor pointed out, the coup created 'a new sense of insecurity' all round and teachers who decided to emigrate were quickly accepted in Australia and New Zealand. The loss has been particularly serious in the scientific disciplines.

90% of the USP's recurrent expenditure is covered by member government contributions with the remainder coming from Australia and New Zealand. For capital investments, there is heavy reliance on external donors.

In both of Fiji's main ethnic communities, a strong commitment to the family ensures that there is relatively little absolute poverty although things may be changing as the country become more urbanised. It is rare to see beggars in the streets in the South Pacific but Suva, sadly, has a number of these.

The overall picture is of a country with very considerable potential in both human and natural resource terms which needs to overcome a number of challenges to secure a more prosperous future. Some of these challenges - adapting to the world of free markets, tackling bureaucratic impediments, bringing development to rural villages, improving the infrastructure, and so on - are familiar to all developing countries. The single most important constraint, however, is the big ethnic divide, and the political uncertainty which flows from this. And this is something which can only be solved by the people of Fiji themselves.

'The last ten years have been very educational for me'

It is almost ten years since Sitiveni Rabuka led the military coup which toppled the newly-electerl coalition government The stormy events of 1987 are long gast end Fiji has returned to more peaceful ways, but the country is arguably not yet at peace with itself. Major-General Rabuka is now the erected Prime Minister, having led the SVT to victory at the polls in 1992 and 1994. But the gulf between the native Fijians end citizens of Indian descent remains - indeed, it is institutionalised in a political system which ensures a parliamentary majority for the former. A constitutional review is currently under way end a new text must tee adopted by July 1997. For both sides, the stakes are high. In this interview, Prime Minister Rabuka speaks frankly about the crucial issues facing Fiji as the nation gears up for the great constitutional debate.

Fiji also faces some formidable economic challenges and we began by asking the Prime Minister about these.

- The main challenge is the one that everybody faces: achieving an acceptable rate of growth to ensure job creation and address the unemployment problem. We also want to improve the standard of living of the people, to upgrade our infrastructure, and to develop both the urban and rural areas.

· What sectors do you see as offering the best hope for future growth ?

- We are looking particularly at tourism and the agro-based industries. In the international sphere, we are aiming to boost trade, particularly with our traditional trading partners, Australia and New Zealand, and with new partners that we are trying to cultivate in Asia.

We are very grateful for the Lomé Convention and the various arrangements associated with it - particularly as regards access to the EU market for our sugar products. Although it would be desirable for us not to have to rely on preferential pricing for sugar, for the moment, there is no alternative. And while we are looking for alternatives and seeking to diversify our economy, we will need that system to remain in place. We would like to continue the dialogue to ensure that this happens.

In the area of trade, as I say, our focus is on Australia and New Zealand, and the regional trade agreement that the Pacific island territories have with them. This agreement is currently under review. One important aspect is the clause governing the rules of origin. If we can convince Australia and New Zealand to reduce the local input requirement from 50% to 35%, then we won't need any aid from them. The effect will be to secure existing jobs and, indeed, to increase employment, particularly in the garment industry. At the moment, most of the textiles we import for further processing come from Australia. Because of the market we have to sell to, it is very good quality material. This means the costs are high, in comparison with the local input needed to turn it into finished products, and this makes it difficult for us to get up to the required 50%.

If we don't get that reduction, things could go in the opposite direction. Manufacturers might relocate and we could be facing jobs losses. You have to remember that we are competing with Asian producers who have very low wage costs.

· Is this proposal for a reduction in the local input requirement on the agenda with the Australians and New Zealanders ?

- The review actually excludes the clause on the rules of origin. Having said this, we have effectively raised the calculation of our local input in negotiations on a series of other points. On paper, the 50% figure is unchanged but in fact, there has been a reduction of about 5%, thus giving us a little margin.

· On the sugar issue you said you were hopeful that some form of preferential access to the EU market would be maintained. Isn't there a concern that this may not last beyond the year 2000, particularly given the increasingly liberal world trading system ?

- Yes, and we are looking at that. We should be gearing ourselves up for what happens at the end of the current Lomé agreement. It remains to be seen whether, with the WTO and the new trends, the curtain will suddenly be brought down on 1 January 2000, or whether there will be a grace period in which we are given time to consolidate our diversification.

· The other big issue in the sugar sector concerns the impending expiry of the land leases.

- That is a local issue and a very important one. It has high priority on our government agenda. We are currently talking to the landowners and lessees, explaining what will happen. The legislation (the Agricultural Landlord and Tenant Act) makes no provision for further extensions to the leases, which are now nearing their end. Do we need a new act or should we amend the present law to allow extensions beyond the 50 years originally allowed for ? And if we are to do that, what happens to the compensation provisions? At the moment, these are viewed in a rather one-sided way. The emphasis is on the situation where the landlord compensates the tenant for improvements made to the land. But the rules also provide for compensation in the other direction where the value has been reduced. This may be due to constant cultivation over 50 years. What if the owner wants to return the land to its original use, planting taro, yams or cassava, as his father may have done fifty years ago, and finds he can no longer do so ? There has to be a balancing act here.

Hopefully, most of the land will be leased again under a new agreement or under an amendment to the existing law - because we will need to continue sugar production. It is also worth noting that some sugar farmers are beginning to diversify into other crops, both subsistence and commercial.

· What arrangements do you envisage for those farmers who do not have their leases renewed ? Will they be relocated ?

- Right now, we are looking at the use of state land. There are two basic categories here - what used to be known as 'Crown Land under Schedule A' and 'Crown Land under Schedule B'. Schedule A covers the land not claimed by anybody during the Commission that was set up to determine the ownership of land in the very early colonial years. Schedule B is land that belonged to a community or landholding unit that has since died out: in other words, where there is no surviving member of the land-owning unit. So we have those parcels of land available. My party's policy is to restore land to the traditional owners where possible, but in those cases where you cannot identify the original owners, there will be land available for resettlement - although resettlement is perhaps not a very good term to use.

· It is somewhat emotive.

- It implies taking a person, family or community from somewhere and planting them somewhere else - and I hope we can avoid that. On the other hand, if you look at what people are doing nowadays, everybody's relocating. People are always resettling, moving away from home and setting up elsewhere. In this case it is perhaps a necessity, in the sense that the legislation has caught up with us.

· Can I turn now to the sensitive issue of the constitution. This is another area where decision day is looming. You currently have a constitutional review under way with the Commission's report due out soon. What do you think will emerge from this process over the next 12-18 months ?

- I don't feel that the constitutional issue is a sensitive one and do not think anyone should feel restrained in asking questions about it. It reflects the reality of the situation in Fiji. There is a requirement that the 1990 Constitution be reviewed and we have a Review Commission chaired by Sir Paul Reeves. He is a very capable man who is a former Governor-General of New Zealand and a very eminent constitutional lawyer. Assisting him, we have two party nominees - one from the main Fijian party and one nominated jointly by the Indian parties in Parliament. I have total confidence in that Commission. I believe they will come up with very objective observations and recommendations.

Let me explain the timetable to you. The report is expected by the end of August. It will be presented first to the President and then to me for submission to Cabinet. I envisage it being tabled in Parliament towards the end of September. We cannot debate it until three months have elapsed from the date it was tabled - which takes us to the end of the year. A lot of work will be needed during the first half of 1997. The Joint Parliamentary Select Committee, made up of members of both the upper and lower houses, will have to work on the report and try and build consensus on the various issues.

Given that the house is racially divided, and the possibility that a premature discussion on the floor of the house may raise the temperature, I would prefer not to have a full parliamentary sitting in the early part of next year. Instead, we should go into committee and deal with it there. And then when we are satisfied that the issues can be brought out into the open, we will debate them fully in Parliament. As soon as we start talking next year, the legislative craftsmen should begin their work. On the basis of this programme, I believe we can meet the deadline to the day, promulgating a new Constitution which has been accepted by both houses on 25 July 1997. So I am very hopeful.

· Without prejudging the final outcome, do you envisage a move away from strict communal separation ? I am thinking here, in particular, of the separate voting lists ?

- I think there may be provision for some cross-communal voting. There was something like this in the 1970 Constitution which had both communal and national rolls.

· What about the longer term. Do you foresee a political system developing in Fiji where ethnic origin is irrelevant - perhaps a 'right-left' divide, if that is still a meaningful concept ?

- I am not bold enough to say that that will happen. I have seen the darkest side of Fijian nationalism. I have seen the fear that was in the Indian population in 1987. But if we move too quickly to remove the racial safeguards that are in the Constitution, we may run the risk of prolonging the bad relationship between the races that we now have. So I would say we should proceed very cautiously and let the natural healing process take its course. We also need to look beyond the Constitution at aspects such as our education system and enhancing the ability of the Fijians to compete.

· I believe the education system is also very divided.

- Some schools are reserved for Fijians although, slowly, there are Indians from families close to the schools who are beginning to enter them.

· Do you think that this is a promising sign for the future ?

- I think so. I went to a purely Fijian school and when I came out of that, everything was Fijian for me. I went straight into the army which is another Fijian-dominated institution. It was not planned that way. It is just the way it happened. My tolerance level of other races was very low. But you cannot expect somebody who gets to this level of leadership to have a low racial tolerance level. I must admit that the last ten years have been very, very educational for me - very good for my own being. I consider what I used to think before and the way I used to feel before. I have never been threatened by an Indian, but I had always been in Fijian 'safe' areas - a Fijian school and then in the army. But since coming out of that sort of cocoon, I have managed very well to accept that I have to compete with them, I have to look after them, and I have to devise policies and programmes that will be good for them as well as being good for us.

· One final question. Do you envisage Fiji seeking to rejoin the Commonwealth in the near future ?

- I think seeking is the wrong word. We will do what we feel is good for Fiji and its people. The people of Fiji are those who are here now but it will include some of those who have moved on looking for greener pastures and who are willing to come back. We were not expelled from the Commonwealth; our membership lapsed. It is up to the Commonwealth to say whether they are prepared to reconsider our member ship.

General information

Area: 18 272 km². Fiji has two main islands (Viti Levu and Vanua Levu) and about 300 smaller ones. It has an Exclusive Economic Zone of approximately 1.3 million km²).

Population: 790 000

Population density: 43 per kilometre²

Capital: Suva (situated on the island of Viti Levu)

Main languaqes: English, Bauan

(main Fijian language)

Currency: Fiji dollar (F$). In June 1996, 1 ECU was worth approximately F$ 1.80. (US$1 = F$ 1.40)

Politics

System of government: A bicameral parliamentary system consisting of an appointed Senate and an elected House of Representatives. The President is a non-executive head of state chosen by the Great Council of Chiefs. The President appoints the Prime Minister.

Under the Constitution, adopted in 1990, the Parliament is divided along racial lines. The Senate has 34 members, 24 of whom are indigenous Fijians. In the 70-member House of Representatives, 37 seats are reserved for native Fijians, 27 for Indo-Fijians, 5 for 'general voters' (other ethnic groups) and 1 for Rotuma Island (whose inhabitants are Polynesian). The 1990 Constitution provides for a review within seven years and discussions are currently under way with a view to amending the Constitution by the 1997 deadline.

President: Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara

Prime Minister: Major General Sitiveni Rabuka

Main political parties: Soqosoqo ni Vakavulewa ni Taukei (SVT - Fijian), National Federation Party (NFP - Indian), Fiji Labour Party (FLP - Indian), Fijian Association (FA - Fijian), General Voters Party (GVP).

Party representation in Parliament (1994 election result): SVT 31, NFP 20, FLP 7, FA 5, GVP 4, Others 3.

Economy

GDP: (1995) F$ 2.85 billion

Annual GDP per capita: approx US$ 2600

GDP growth rate (1995): 2.2% (2.9% predicted for 1996)

Principal exports (1994): Sugar (US$ 182m), Garments (US$ 96m), Gold (US$ 43m), Fish (US$ 38m), Timber (US$ 21 m) Main trading partners (in order of importance):

Exports - Australia, UK, USA, Japan, New Zealand.

Imports - Australia, New Zealand, USA, Japan, Singapore.

Trade balance (1994): exports - US$ 547m, imports - US$ 826, deficit - US$ 279m. The current account figures also usually reveal a deficit but this is much smaller due to tourism earnings and official transfers.

Inflation rate (1995): 2.2%

Government budget (1996): revenue - F$ 759m, expenditure - F$ 851 m, deficit - F$92 (about 3.5% of GDP)

Forma/sector employment: 98 112 (out of a total economically active population of about 265 000)

Social indicators

Life expectancy at birth (1993): 71.6 years

Adult literacy (1993): 90.6%

Enrolment in education: all levels from age 6-23: 79%

Human Development Index rating: 0.853 (47th out of 174)

Sources: Economic Intelligence Unit, UNDP Human Development Report, 1996, EC Commission.

'We need to move to a more racially neutral system'

Fiji is not unique in having a political system that is heavily influenced by racial or communel issues In places as diverse as Northern Ireland, Belgium, Guyana and Trinidad - not to mention many parts of Africa - people vote for parties which claim to represent the particular ethnic, religious or linguistic group to which they belong. Where Fiji is different, however, is in having a Constitution that gives primacy to one particular community. Since the 1987 coup, native Fijians have held the upper hand with a guaranteed majority in Parliament and a firm grip on the levers or power.

The 1990 Constitution, adopted when communal feelings were still running high, contained a requirement for a constitutional review within seven years. When The Courier visited Fiji (July 19961 the work of a three-member Commission appointed to carry out the review and make recormmendations was nearing completion. All sides seem to accept the need for reforms designed to help bridge the sharp racial divide.

The big question is how radical these reforms are likely to be. We sought the views of Jai Ram Reddy, the leader of the opposition National Federation Party (NFP) which has the support of most of the country's Indian (Indo-Fijian) community.

· You are the first opposition leader I have met who cannot, constitutionally, become Prime Minister. How do you feel about that ?

- It is something that rankles with me - the mere thought that I am not equal with my fellow citizens of other races. I think that's generally the way the Indians feel here. All the constraints and limitations, the denial of basic human rights, are the source of a great deal of unhappiness.

· You talk about basic human rights. Obviously, the political aspects are very important but I get the impression that, in other respects, this is a fairly free and easy society: there is free expression, for example.

- Yes, but free expression is only one aspect of human rights. The fact is that discrimination based on race is widespread and institutionalised. About 45% of the population is Indo-Fijian but you will find they are not fairly represented in the higher levels of the public service. At the Permanent Secretary level, there is definitely a government policy to have a limited number of Indians - and there are hardly any in the more crucial ministries. The same is true of managerial positions throughout the public sector. In the statutory bodies and major public undertakings, there is a deliberate policy of excluding Indians. So we are very much a marginalised community in the public sector.

· Wouldn't it be true to say that Indians have quite a lot of economic power ?

- No, I don't agree. There is a tendency for people who come here, end for some people in Fiji, to project this image of Indians controlling the economy. It is a fallacy. It all boils down to how you define economic power.

Let's take natural resources. The land, and therefore the forests, are almost exclusively owned and controlled by native Fijians. Even in the corporate sector, the largest business undertaking is the manufacture of sugar, and 80% of the shares are owned by the government. The Indians don't own this industry. They are the small sugar cane producers working on ten-acre plots. And who controls banking and insurance ? Certainly not the Indians. Most of the financial services companies are foreign-owned.

The area where the Indians are most visible is in the retail sector. But those little shops you see in the towns are small family businesses. The shopkeepers work up to 15 hours a day, and you will discover that many of them do not even own their premises; they are tenants. So the idea that Indians control the economy is a bit of a myth.

· The Constitution, and in particular the system of racial differentiation for voting and holding certain offices, is obviously a key issue for you. With the Constitution currently under review, what is your party's policy in this area ?

- The first elections under the current Constitution took place in 1992 and we took part in them under protest. We made clear that our participation should not be construed as acceptance of the system. Indeed, the sole issue on which we campaigned was our rejection of the Constitution. But we accepted the fact that we needed to get into the system as it was, and to try and create an environment where there would be widespread appreciation that it had to change. The 1990 text, in fact, laid down that it had to be reviewed by the seventh anniversary of its promulgation. I think the architects of the Constitution realised themselves that it was deficient. And we laid great emphasis on the need for dialogue; a general recognition that the country would be much better off with everybody working together and that there was nothing to be gained by oppressing or marginalising a community. And that is the kind of environment we have tried to create.

· The Constitutional review will shortly be published. What do you hope will come out of that exercise ?

- I am reasonably optimistic. I think the environment is more favourable now and there is a general recognition that the system has to change. I am sure you will get confirmation of this when you talk to the government side. We need to move away from this very polarised, compartmentalised political system to a more racially neutral one. I think views may diverge as to how far we should go. That will be the contentious issue. But I believe we will make progress.

I certainly think we will get a good report from the Constitutional Review Commission. One of our fears, when we started on this journey, was whether it would be independent and be given fair terms of reference. Largely because of the cooperative and accommodating attitude that we ourselves adopted, and to which the government responded, we were able to get a Commission that was well-balanced. We are very fortunate to have Sir Paul Reeves, a former Governor-General of New Zealand. His independence is taken for granted. The Commission also has one nominee from the indigenous side and one from the Indo-Fijian side. So we certainly expect a good report. There is already a kind of acceptance I think on all sides that political parties need to prepare themselves for a more multiracial approach to governance in the future.

· On this point, I see that the SVT (the governing party) is looking at the idea of opening up its membership to other groups.

- That's right.

· Do you think there will be many nonnative Fijians interested in joining ?

- Not straight away but at least it is a beginning. It is an acceptance that they can't remain racially exclusive. If, for example, the Commission recommends a move toward a racially neutral system - at least for a certain number of seats - then it would be important for the SVT to have non-Fijians in their party.

· Can I turn to economic issues, which I presume cannot be divorced altogether from political ones ? There is a lot of discussion about the future of the sugar industry which is tied in with the question of renewing the land leases This is an issue which is due to be resolved soon. How concerned are you about the impending decision on the leases ?

- This is something that concerns us very deeply. As you correctly observe, you can't separate the political and economic aspects. The two are very closely interlinked here - perhaps more so than in other countries - because of the land situation. The bulk of Indian peasant farmers, both within and outside the sugar industry, are on leases that will begin to expire next year. If these are not renewed, the problem will not just be an economic one but an enormous human one. What do we do with these people who all belong to a particular racial group. It really boils down to our very survival. Despite the growth in the towns, the bulk of the people are still rurally based. They are small subsistence farmers, living in the country areas with no more than 10 or 12 acres to cultivate. So the social implications of non-renewal in terms of poverty, dispossession and hardship are enormous.

· But how real is the concern ? Surely, the overwhelming economic logic is for the leases to be renewed. After all the land is being put to productive use at the moment

- Yes, but unfortunately, when you have a communal dimension to the problem, logic does not always prevail. If you think about it, there was no logic in the events of 1987. The trouble is that every issue here has a racial twist. After the coup, communal sentiments were aroused and sharpened. There was a prolonged period of anti-lndian propaganda and in that environment of anger, a highly racial constitution was adopted. There were people in positions of influence openly advocating non-renewal, threatening to take all the land back. Now they need to undo all this and it will not be easy, given the enormous strength of feeling that has been aroused. Having said this, I believe that we are now in the process of restoring sanity to our public life. It is also beginning to dawn on everybody that the sugar industry is vital for Fiji and it will continue to be so for some years to come.

· I have heard that view expressed on all sides, but I wonder if people are sufficiently aware of the implications of global liberalisation. It has been suggested that this will make sugar increasingly unviable.

- I think a lot of people are unaware of the implications, because there has been very little public education in this field. But amongst those 'in the know', there is certainly an appreciation. I am a member of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Sugar and we were recently addressed by the head of the marketing company and the head of the Sugar Commission. At that level, there is an awareness, but if you speak to the average farmer who has been growing and selling sugar for many years, he will probably assume that life will just go on as before.

Isn't it true to say that sugar depends heavily on the Lomé Convention arrangement with the European Community ?

- Very much so. In my view, the sugar industry is run so inefficiently that but for the huge subsidy we get from the European Community, it would not be viable.

Presumably, this means that measures must be taken to improve efficiency ?

- Yes, absolutely. But the first issue to resolve is the land question.

There is no point talking to the farmers about efficiency - asking them to improve their husbandry and focus on sugar content rather than the quantity of cane produced - when they don't know if they will have land to cultivate after next year. So you see all other issues have become completely subsidiary to the tenure question. At the moment, we are in a limbo. The government and the people urgently need to resolve this problem. Then we can put it behind us and address the other concerns.