09 September 1898

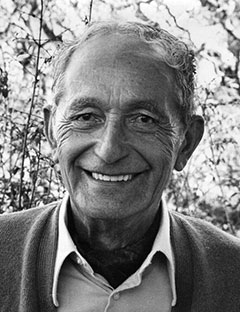

Born at Harataunga (Kennedy’s Bay) on the eastern coast of the Coromandel Peninsula on the 9th of September 1898, Pei te Hurinui was the son of Daniel Lewis, a European storekeeper, and Pare Te Kōrae Poutama of Ngāti Maniapoto (born ca.1878), daughter of Poutama II and Paretuaroa. Daniel Lewis, with his brothers Samuel and Hyman, operated a store at the site of the Poro-o-tarao tunnel in the King Country during the construction of the main trunk railway line. It was here that Pare Te Kōrae’s eldest son, Michael Rotohiko was born in 1895. Pare Te Kōrae also bore two daughters, Julia and Lena, and a second son Pehi (Pei) to Daniel Lewis. The marriage was a brief one for Daniel left Aotearoa with his brothers to enlist for service in the Boer War and he later settled in Australia and never returned (Hurst, 1996, pp. 6-7). Pare Te Kōrae later married David Jones, a farmer, of Ngāpuhi descent, and they bore five children. Pare Te Kōrae’s elder children to Daniel Lewis, including Pei, took their stepfather’s surname.

During his early years, Pei lived at Te Kawa Kawa (now called Ongarue), a small township on the banks of the Ongarue River; approximately 16 miles north of Taumarunui. Pei was adopted in his infancy by his mother’s grand-uncle, Te Hurinui Te Wano, and the years spent with this koroua (grand uncle) had a profound effect on him. It was during this time that he was initiated into the lore and traditions of his people. Bruce Biggs (2005) notes the following of Pei’s childhood: “A sickly child, troubled by dreams that came to be considered portents of death in the tribe, Pei underwent ancient rituals. Besides putting an end to the troublesome dreams, these confirmed a commitment to his traditional Maori heritage”. Pei would later recall the influence of his koroua (grandfather/ elderly man) (Jones, 1982, pp. 10-11):

My granduncle often would recall me from my youthful games and set me to work on his manuscript books. These books contained genealogical tables, tribal traditions, ancient songs, and ritual. The task I was first set to do was to copy pages of manuscript into new books. He flattered and encouraged me in this work by words of admiration for my handwriting.

At times I found the task irksome, and it was hard to put up with the shouting and laughter of my companions in their play. The temptation was strong to rush off and leave my granduncle’s books behind. In time, however, I became very interested in the subject matter of my writing.

When I started to question my granduncle about some of the rather obscure passages in the stories or the songs, a look of deep contentment came over his smiling face before he would answer me. From those early years I became absorbed in the study of ancient ritual, tribal traditions, and the esoteric lore of our people that it became a passion with me.

It was in this way, at a comparatively early age, that my grandfather implanted in me and I acquired an abiding love for the ancient lore of our Maori people.